Shards of clarity

Trigger Warning: Mental illness, self-abuse, suicide

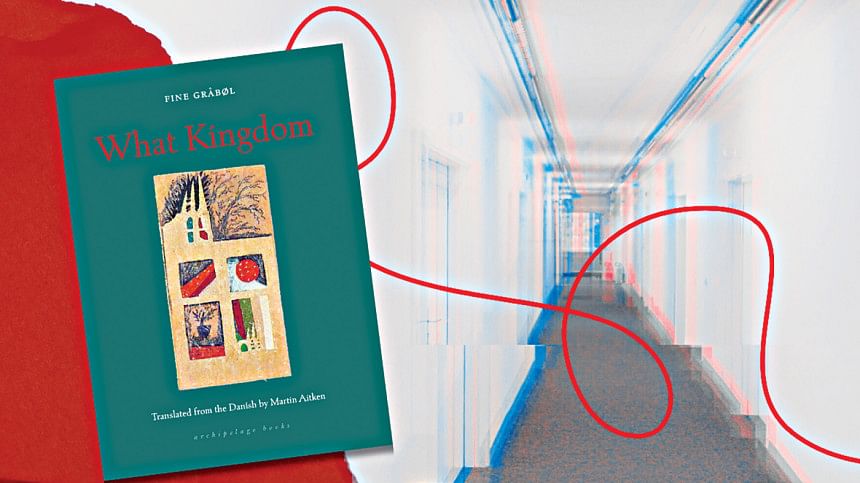

Beginning to read Fine Gråbøl's What Kingdom, translated from the Danish by Martin Aitkin, is like sitting in a silent room, alone, and a voice begins to speak as though from beside you. "Of all the hours of day and night I like the earliest morning best." With that, Gråbøl's nameless narrator introduces you to the space of the text. This space is both her mind, which feels the need to arrange its thoughts in rows, where at night these thoughts "tumble like gulls around stale bread in a greasy town", and this space is the institution in which she resides as a young person in need of psychiatric care in Copenhagen, Denmark.

The novel begins in media res and strikes up an immediate intimacy with the reader. It takes you on a tour of Sweet Corridor's characters and rituals. Sara, Lasse, Hector, and Marie are the narrator's neighbours on this building's fifth floor, where young adults ages 18-30 temporarily live. The facility itself is a state sponsored residence, once an old people's home and now "a kind of exploration into having a home" for individuals suffering from psychiatric disorders who need round the clock support. Through the narrator's blinking, roving gaze, we learn about the floors below them which are similarly designed, but where the residents are permanent and where Waheed blares 50 Cent through the night. We learn to see the Lord of the Rings poster in the young people's corridor and the furniture that populates their rooms. We step into the rhythms of their coffee making and meal making, their sleepless nights and often-difficult days, their relationships with the pedagogues on duty by day, who are different from those on duty by night. "I know what's going to happen today; the birds know. I know what's going to happen today; the treetops know, they receive the wind. No disruption in the movements of the leaves. No disruption in my hand's collusion with the mug. No disruption in the relationship of my skin to the surroundings; my nails know, and the clouds."

It feels as though the sentence itself will slip through the cracks in these sections, if the narrator doesn't cram them enough with the solidity of facts. Sensory observations, thoughts made tangible and lined into rows, scaffold the narrator's grasp at stability throughout the book. By the end of the first section, titled "Sweet Corridor Law", the reader has glimpsed enough into the patterns of their days to feel initiated into the residents' existence here. But it's a gaze through cracked glass, each scene, each episode shuttering into and out of clarity within the space of one to two pages, made up not so much by patterns as arbitrary rituals that make up their own internal rhythm. Some of these episodes gleam quietly into focus through one solitary sentence on a page.

Gråbøl makes the text shift from foggy recollections to instances of stark clarity in these scenes. In Aitken's translation, the second person point of view places the reader in the body experiencing this dissociation.

While this effect continues throughout the novel, the text modulates tone and psychological clarity. On a larger, architectural level, the airiness of 'Sweet Corridor Law' gives way to what feels like a more constricted second section. 'Containment' seats the reader in longer drawn moments of upheaval. Often, we arrive at the scene after the fact. After what sounds like a suicide attempt by the narrator. After she has poured boiling water on herself. Before, and then after, she has crumbled against an unwanted announcement from the staff. The 'I' appears and reappears in this section, drawing us into realisations of hazy candour. "I get to my feet, something wants out of my chest, my stomach's a warm belt," the narrator shares. "I own only the illness inside me, but the rest is something they take away."

Gråbøl makes the text shift from foggy recollections to instances of stark clarity in these scenes. In Aitken's translation, the second person point of view places the reader in the body experiencing this dissociation. But in her more lucid moments, it's a third person point of view that allows a wryness to creep into the narrator's tone, as she dissects the language and protocol surrounding institutions such as the one she inhabits. "It's not just up to the contact person when a new relationship needs to be established, it's up to the residents too," she writes. "The difference is that one of them gets acknowledged for the work they put in, the other doesn't." Or, in an even more powerful pronouncement: "They call containment of the emotional register treatment."

*

Fine Gråbøl was a poet before publishing this debut novel. The signs are there in the book's sharply crafted sentences. A musicality, an attention to imagery and rhythm. But, in Aitken's English translation, these qualities do more than draw attention to pretty prose. As a reader you feel like you're being guided by an intelligent mind, by a narrator who reads deep into the people and spaces around her. Whose inner language leans towards the poetic when she's trying to find comfort in sensory detail, who swivels between the I, the you, and the we to draw the reader near and far depending on how much she's able to share. And whose acute observations of her circumstances unpack for us the gendered and capitalistic language through which their experiences under the Danish welfare system are straitjacketed.

Of the imbalances in the system, Gråbøl's narrator draws our attention to the precarity of her and her neighbours' relationship with those looking after them. It's a connection based on a one-way stream of trust and forthrightness. The inhabitants must share their secrets, reveal themselves at their most vulnerable in order to receive effective care. But they must remember not to become emotionally attached with these people who are, ultimately, doing their jobs by offering this support, who owe the inhabitants no details of their own lives in response. Whose availability may shift, and even stop, depending on their employers' policies. In one of her most poignant monologues in the text, the narrator admits that in her most recent stay at the hospital, she wore only the scrubs she was provided—an emotional guard against giving in to the delusion that a hospital can ever become home, however long or frequently you might stay there; that its blurring of time can ever make it anything more than a thing to be borne.

*

A movie that the narrator and her co-residents watch at the facility, often, is Girl, Interrupted, which is adapted from Susanna Kaysen's 1993 memoir about the author's stay in an American psychiatric hospital when she was experiencing a borderline personality disorder. In the 1999 adaptation starring Winona Ryder and Angelina Jolie, Dr Wick, the head psychiatrist, echoes a question originally raised by Hercules in Seneca's tragedy, Hercules Furens.

"What place is this, what region, what quarter of the world? Where am I? Under the rising of the sun or beneath the wheeling course of the frozen bear?" Hercules wonders upon returning to a life from which he feels estranged. Dr Wick, in Girl, Interrupted, points out a similar crossroads facing the character of Susanna in the movie. "What world is this?" he repeats Hercules' lines, "What kingdom? What shores of what worlds?…How much will you indulge in your flaws? What are your flaws? Are they flaws? If you embrace them, will you commit yourself to hospital…for life? Big questions, big decisions!"

What Kingdom borrows its title from this palimpsest of questions, but the scene itself is given a fleeting reference in Gråbøl's novel. It's another scene from Girl, Interrupted that carries more weight for the facility's residents. Just before 'Sweet Corridor Law' ends, as Sara and the narrator sit watching the movie on a Friday film night, Sara shares that her favourite scene is when the girls abscond from the institution. The film should stop right there, she declares, on that note of agency taken up by characters who have been suffering psychological instability.

This is the project of Gråbøl's novel. As "Secrets", the book's last section, creeps in, Gråbøl's narrator switches to a playful, whispered 'we'. The text takes on an air of clandestine rituals being revealed—how Sara massages hair dye, a vivid red, into Marie's hair; how Lars and the narrator perform "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" to a lawn of dancing onlookers; how the residents decide to jostle the rules put in place to protect them.

As the book reaches this revelrous fever pitch, What Kingdom makes a final flourish in the point it has been trying to make. Stories about neurodivergence and psychological disorders can be told without decentering those who experience it. They can be told with agency given to those whose stories they are, and this can make for fascinating craft choices in a text. As a reader, I wasn't propelled through this book because it was trying to demystify—and therefore exocitise—mental health issues. I was immersed in its voice, in its perception of space and bodily experience, and I trusted that voice to give me as deep or distant a glimpse into her experiences as she herself would choose.

Sarah Anjum Bari is a writer and editor pursuing an MFA in the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa, where she also teaches literary publishing. Her essay, "Strains", was shortlisted for the 2024 Queen Mary Wasafiri New Writing Prize. Reach her at [email protected] or at @wordsinteal on X.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments