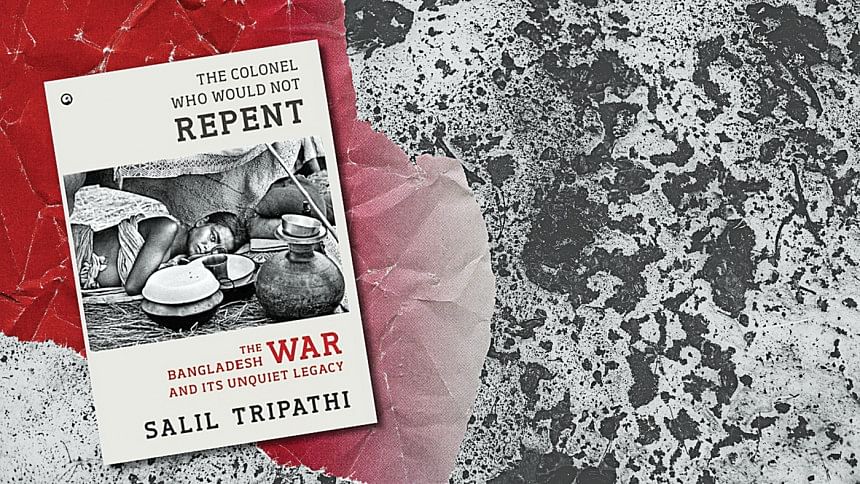

Unquiet legacies in Salil Tripathi’s ‘The Colonel Who Would Not Repent’

Every December, my reading group chooses a book related to 1971. In 2015, for example, we read Qayyum Khan's Bittersweet Victory and a few years earlier we read Siddik Salik's Witness to Surrender. On December 17, 2016, we chose Salil Tripathi's The Colonel Who Would Not Repent: The Bangladesh War and Its Unquiet Legacy. I had met Salil Tripathi when he was in Dhaka researching the book. The book was subsequently launched in Bangladesh at the Hay Festival – as it was still called in 2014. Somehow I missed the launch and did not get the book till much later. I mistakenly assumed – from the title – that it focused on Colonel Farook Rahman, one of the assassins of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. It was only after getting the book that I realized that, though the book begins with the hanging of Sheikh Mujib's killers, Farook Rahman is not the protagonist – or even the antagonist – of the book. He is one of the many legacies of the 1971 war. And the war itself is part of the story of this land from its early beginnings in the 1905 Partition of Bengal to the present – and beyond.

I could almost hear the groans of the members of my group when I suggested another book on 1971. They were too polite to ask the question that I knew was in their minds: Why another book about 1971? Don't we know all about 1971? Haven't most of us in this group – as we are almost all of a certain age – lived through 1971? And haven't we read enough historical accounts and fictional accounts about the war? What more is there to read? Or to discuss?

And yet, there is more. As Salil Tripathi's book puts it, the war might be over but its legacies remain. Of course Tripathi tells the story of 1971 at secondhand: as he has read about it in books and newspaper accounts and heard about it in the many interviews strewn throughout the book. It is true that, perhaps because Tripathi is not a meticulous historian but a journalist, the book suffers from numerous errors. Thus, he mentions the destruction of the Dacca Radio Station in March 1971. The name of Abdur Rab Serniabat is repeatedly misspelled. Readers who would want a definite answer to the question of numbers – How many were killed? How many were raped? – are given accounts of numbers given by others rather than any definite answer.

In "Between 'Correct' and 'Inclusive' History," an article published in the Dhaka Tribune in December 2016, Afsan Chowdhury asks whether we want "correct history" or "inclusive history." "Correct history," of course, is ironic because it is not inclusive and therefore not correct either. "Correct history" is what is politically correct at a given time because of the powers that be. Tripathi attempts to provide an "inclusive history" of 1971 – which also attempts to be truly correct. It is this that gives The Colonel Who Would Not Repent its importance. Above all, as an outsider, Tripathi can look impartially at historical events and personalities. Perhaps he cannot answer all the questions, but at least he can provide us with the questions.

Thus, one of the questions Tripathi asks – which does not fit the accepted narrative – is, How prepared was Bangladesh for the armed struggle? He notes that Tajuddin Ahmed and Kamal Hossain were two of the last persons who met Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on the night of March 25. After the crackdown, Tajuddin Ahmed left for India but Kamal Hossain, after moving from "house to house," gave himself up on April 2. In his interview with Tripathi, Kamal Hossain describes the event. As he was being taken to the airport, he was questioned about what he and Tajuddin Ahmed had been planning to do. He told Tripathi that "They had made no plans" (86). The absence of preparations for an independent Bangladesh is voiced indirectly through Asif Munier, whose father, Munier Chowdhury, was picked up on December 14 and killed. Asif Munier noted his mother's anger against Mujib. "Asif recalled: 'She said the Liberation War was a national movement. But why could he not have prepared the country better? Why did we have to wait for the blow on 25 March?'" (188).

Tripathi does not raise the issue of who declared independence. However, he quotes Editor Mahfuz Anam's reaction to hearing "the faint voice of Major Ziaur Rahman who declared, in the name of Bangabandhu Mujib, that Bangladesh was now a free country." According to Anam, "That declaration was a source of moral support for us and showed great moral courage. It told us something was happening; that some effort was being made. We didn't know where the declaration came from, but it was important that the declaration was made" (88).

Tripathi does raise the issue of the numbers killed in 1971 – but does not provide any conclusive figures. Were they 26,000 as the Hamoodur Rahman Commission noted, 3 million as Bangladesh – following Sheikh Mujib's statement to David Frost – believes, 57,000 as mentioned by David Bergman, between 50,000 and 100,000 as claimed by Sarmila Bose? Tripathi explains the confusion between lakhs and millions and quotes Peter Kann at length who concludes, on the basis of calculating how many soldiers would have been involved in the killing, that "The three million figure makes no sense" (315). Tripathi stresses that it is not numbers that matter so much as holding people accountable, as in knowing what happened. Again, he quotes Irene Khan at length on the prosecutions: "Those crimes have remained uninvestigated; it is extremely important that there is a commission of inquiry, if Bangladesh is to put a closure to this chapter of its history. Even if you will have only a limited number of prosecutions, you need a full record of what happened" (317).

Tripathi has a chapter on birangonas – as well as an appendix including interviews with fourteen birangonas. The chapter on birangonas ends on a positive note, with Tripathi narrating how Ferdousi Priyobhasini managed to survive the trauma of rape by seeking release in art. He stresses that Bangladesh took remarkable steps to rehabilitate women who had suffered in the war. The recognition of women's contribution to the Liberation War, by acknowledging them as "birangonas," war heroines, took place soon after the war. Tripathi points out that the appellation of "birangona" was given a few days after the war, on December 22, not in early 1972. He also suggests that though Mujib was sympathetic to raped women and widows, he did not want to have anything to do with the war children born to women raped by Pakistani soldiers. Tripathi quotes Mujib's comment to Neelima Ibrahim as narrated in Ami Birangona Bolchhi, "Please send away the children who do not have their fathers' identity" (219). Tripathi notes how Bangladesh in 1972 encouraged the adoption of war babies, though, as a Muslim country, Bangladesh was against adoption. Tripathi thought that the stories of the missing war babies would never be known. In one instance he has been proved wrong. Thanks to the efforts of Mustafa Chowdhury, the stories of fifteen war babies adopted by Canadian families has been documented in his book, Unconditional Love. However, Chowdhury's book, published in 2016, is only about a small number of war babies. The stories of countless other war babies – who were not aborted – are not known and perhaps will never be known.

Despite Sheikh Mujib's aversion to war babies, Tripathi stresses that Mujib was deeply sympathetic to women who had been affected by the war. He notes how warmly Sheikh Mujib greeted Basanti Guhathakurta, the widow of Professor Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta. He also narrates the story of how Sheikh Mujib saved the marriage of a woman whose freedom fighter husband, suspecting her of infidelity, wanted to divorce her. Tripathi does not name the freedom fighter, though people familiar with the situation would be aware whom he was talking about.

Salil Tripathi's book attempts to look at historical events as objectively as possible, quoting written sources as well as oral ones. He also attempts to look at the legacy of events subsequent to 1971. He believes that there has been no closure either of the killing of Mujib or Zia. He notes how Mujib's house on Road 32 Dhanmondi as well as the Circuit House of Chittagong where Zia was killed still have the blood that was shed there in August 1975 and May 1981 respectively. Is it time to wash the blood away?

Among the many persons Tripathi interviewed for the book was Meghna Guhathakurta, whose father, Jyotirmoy Guhathakurta, brutally wounded on the night of March 25, succumbed to his injuries a few days later. Tripathi quotes Meghna musing over justice and revenge. Yes, she says, those who killed her father and countless others in 1971 deserve to be punished. However, she stresses, "Revenge doesn't make sense. . . . Just because my father died doesn't mean that yours has to die. But recognition, that something took place, and the fact that it should not take place again – that is justice" (333).

Tripathi recognizes that healing wounds is not a simple matter, but Bangladesh must move beyond "simplistic notions of victims and perpetrators." He suggests that "the resolution is through negotiation, and not through violence. It means respecting the dignity of the other. The identities of 'perpetrators' and 'victims' are fluid, just as one person's terrorist is another person's freedom fighter. When these identities are fluid, we must remember that not all Bengalis were victims, nor all Biharis perpetrators or collaborators, and not all Punjabis killers. Instead of living in the past, it is time to leave the past" (334). Tripathi's comments are well worth remembering.

At our December discussion, Professor Razia Sultana Khan noted how Tripathi not only narrated the past or commented on the present, but also provided little bits of Bengali culture to give a picture of the land and its people: a song by Lalon Shah, a reference to Bankim Chandra's Ananda Math, a quotation from Kazi Nazrul Islam, lines from Taslima Nasrin, a vignette from Ritwik Ghatak, a couple of poems by Sufia Kamal, a brief description of the holud ceremony where a Muslim bride is smeared with turmeric. Thus, Tripathi's account becomes much more than a bare historical narrative.

Despite its editorial slips and a few factual errors, The Colonel Who Would Not Repent is a book well worth reading. In very readable English, it narrates the history of Bangladesh from the seeds sown in 1905, through 1971 and its "unquiet legacy," to suggestions of future pitfalls to avoid.

Niaz Zaman is a retired academic, writer, translator and a founding member of The Reading Circle.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments