Satyendra Nath Bose, more widely known as Satyen Bose, devoted 24 of the best years of his life to Dhaka University. On 1 July 1921, Dhaka University commenced its academic activities with only four departments, one of which was Physics. Prior to this, on 1 December 1920, P. J. Hartog assumed office as the university’s first Vice-Chancellor.

Satyendra Nath Bose, more widely known as Satyen Bose, devoted 24 of the best years of his life to Dhaka University. On 1 July 1921, Dhaka University commenced its academic activities with only four departments, one of which was Physics. Prior to this, on 1 December 1920, P. J. Hartog assumed office as the university's first Vice-Chancellor. It was Hartog who appointed Walter Allen Jenkins, a Physics teacher at Dhaka College at the time, as the head of the Physics Department. Under Jenkins' leadership, the department began its journey in the magnificent main building of Curzon Hall.

Hartog was an insightful and visionary leader. He aspired to make Dhaka University a model educational institution, akin to Cambridge and Oxford, by recruiting talented educators. Jenkins, too, was a dedicated professional who played a key role in equipping the Physics Department with research-grade instruments and laboratories. From the outset, Vice-Chancellor Hartog was keen on appointing a truly talented and promising young physicist as a Reader in the department. In response to the advertisement, two gifted physicists applied, both of whom had been students of Jagadish Chandra Bose.

P. J. Hartog, a devoted and prudent educationist, forwarded the applications to the newly appointed department head for his opinion. After carefully reviewing the applications, Jenkins recommended Satyen Bose as the most suitable candidate and informed Vice-Chancellor Hartog in a letter. In his assessment, Jenkins noted that while both candidates were strong and innovative researchers, Meghnad Saha had produced more substantial and superior work. However, Bose's most recent article in Philosophical Magazine demonstrated exceptional promise. Additionally, based on personal interactions, Jenkins found Bose to be enthusiastic and highly collaborative, making him a more suitable candidate than Saha.

At Dhaka University, Satyen Bose was teaching Planck's formula in class when he identified logical inconsistencies in the derivation. Imagine how cutting-edge the classroom discussions at Dhaka University must have been! While teaching, Bose recognised flaws in the existing formula and sought to resolve them. He succeeded.

Vice-Chancellor Hartog, placing significant weight on the department head's recommendation, decided to appoint Satyen Bose as the Reader. However, instead of proceeding directly with the appointment, Hartog chose to engage with Bose personally to better understand him. Bose responded to Hartog with letters dated 14 January and 24 February, in which they discussed salary, promotion, and other employment terms. These exchanges, which took place before the official appointment and joining, illustrate the level of importance attached to an entry-level position, with the Vice-Chancellor himself engaging in informal discussions with the candidate.

On 02 July 1924, within three years of his appointment, Satyendra Nath Bose accomplished one of the most groundbreaking works in physics while seated in the Physics Department at Curzon Hall, Dhaka University. This work traces its origins back to 1859, when Gustav Kirchhoff proposed the blackbody radiation concept, describing it as one of the most challenging problems in theoretical physics. Since then, the world's leading physicists had refined various theoretical models to address the problem. In 1896, Wilhelm Wien proposed an empirical formula, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1911, though it only partially solved the problem. In 1905, Lord Rayleigh and James Jeans introduced a model that explained another portion of the blackbody spectrum.

In 1900, the renowned German experimentalist Professor Rubens attended a dinner at Max Planck's residence. During the meal, Rubens discussed his experiments on the blackbody spectrum, lamenting that no theoretical explanation could account for the entire spectrum. That very night, after bidding farewell to his guest, Planck worked through the night to devise a formula. He sent it to Rubens the next morning on a postcard, which Rubens found flawless. In his response, Rubens confirmed that this was the formula physicists had been searching for. However, the way Planck derived the formula was largely an educated guess. His aim was merely to bridge Wien's empirical formula and the Rayleigh-Jeans law. It lacked a rigorous theoretical foundation.

Nonetheless, the destination was now clear. Planck was desperate to find a proper derivation, as were Europe's brightest physicists—Einstein, Debye, Ehrenfest, Rayleigh, and others. Planck eventually derived the formula by assuming that atoms in the walls behaved like harmonic oscillators with discrete energy levels. Although this approach allowed him to derive the formula, it did not entirely satisfy the scientific community, and the search for a more rigorous derivation continued.

At Dhaka University, Satyen Bose was teaching Planck's formula in class when he identified logical inconsistencies in the derivation. Imagine how cutting-edge the classroom discussions at Dhaka University must have been! While teaching, Bose recognised flaws in the existing formula and sought to resolve them. He succeeded.

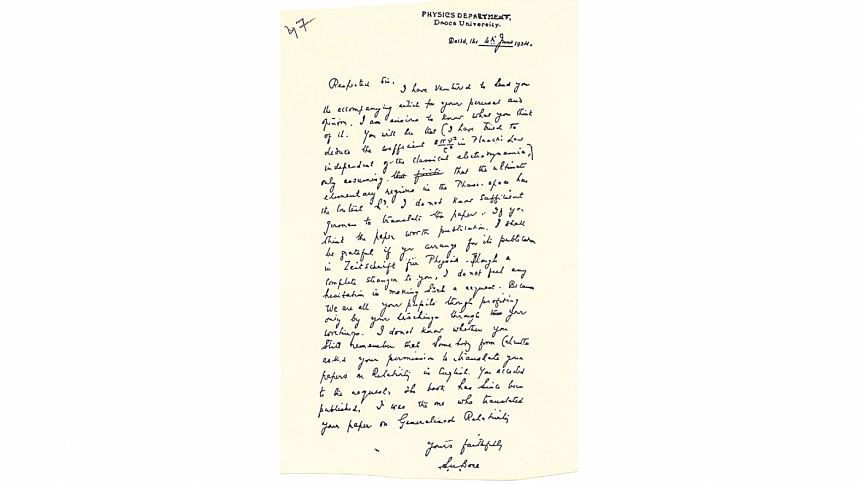

Bose submitted his research paper on this work to Philosophical Magazine. However, it was outright rejected at the editorial desk without being sent for review. Frustrated, Bose sent the paper directly to the great physicist Albert Einstein. The accompanying letter was so well-written and articulate that it could not have been phrased any better. Upon reading it, Einstein was astonished and informed Ehrenfest that what European scientists had struggled with had been solved by an Indian physicist working in Dhaka.

At Bose's request, Einstein translated the paper into German and arranged for its publication in a German journal. At the end of the article, Einstein appended a note emphasising the significance of the work and stating that he would soon build upon it. The paper was published on 2 July, and through this, Satyen Bose's name became eternally linked with Einstein's in the annals of science. Moreover, this achievement established Curzon Hall, Dhaka University, and by extension, Bangladesh, as the birthplace of quantum statistics.

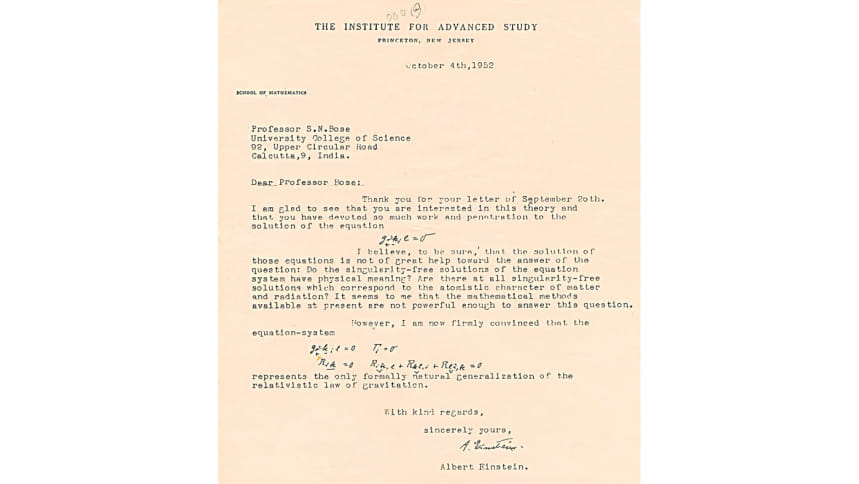

Satyendra Nath Bose's appointment underscores the significance of hiring the right teachers. It was not just about the appointment itself; the importance of promotions at that time becomes evident when we examine the story behind Bose's promotion to professor. After publishing his seminal paper, Einstein facilitated Bose's visit to Europe. Upon his return, Bose applied for promotion to professor but faced competition from Devendra Mohan Bose, a nephew of Jagadish Chandra Bose and Anandamohan Bose. Devendra Mohan Bose held a PhD from the University of Cambridge and had years of research experience in Germany, working alongside some of the most renowned physicists of the era. By contrast, Satyen Bose did not even have a PhD at the time. To strengthen his application, Bose sought a recommendation letter from Einstein.

Both candidates' applications were sent for evaluation to the eminent German physicist Arnold Sommerfeld, who had mentored four PhD students and three postdoctoral fellows who later won Nobel Prizes. After reviewing the applications, Sommerfeld recommended Devendra Mohan Bose. However, the decision ultimately went in Satyendra Nath Bose's favour, as Devendra Mohan declined the offer.

This highlights how rigorous the hiring and promotion processes were a century ago. In stark contrast, today, a 20-minute interview can secure a university teaching position, and the probationary period for promotions has been significantly shortened. Unless we implement at least a three-step filtering process for faculty recruitment, ensuring high-quality hires will remain a challenge. Equally crucial is offering competitive salaries. The fact that Satyen Bose, Jnan Chandra Ghosh, and Ramesh Majumdar joined Dhaka University exemplifies this. Without salaries that exceeded those at the University of Calcutta, they would not have been motivated to relocate to Dhaka, nor would the vice-chancellor of the University of Calcutta have released them.

Now, let us examine the current recruitment process at Dhaka University. Remarkably, the minimum qualification for university teacher appointments in 1921 was a master's degree, and it remains the same even today in 2021. A century ago, candidates had to submit their SSC, HSC, honours, and master's certificates, and the same requirements persist today. Although the recruitment process worldwide has evolved significantly, Bangladesh's system has failed to keep pace.

At Bangladeshi universities, applicants must complete a prescribed form—including fields for nationality, gender, and religion—and submit attested copies of their SSC, HSC, honours, and master's certificates, along with a citizenship certificate and a list of publications, all in eight complete sets. Every document in each set must be attested. Globally, asking for nationality and gender identity in applications is now considered discriminatory. Moreover, requiring SSC and HSC results alongside honours and master's certificates from candidates who already hold PhDs and postdoctoral experience is outdated and redundant. These practices urgently need modernisation.

Meanwhile, universities worldwide have progressively raised the bar for faculty appointments. What once required only a master's degree and an M.Ed. later evolved to require an M.Phil., then a PhD. Today, even a PhD is no longer deemed sufficient; postdoctoral experience has become a standard prerequisite, often involving multiple postdoctoral fellowships. Despite these qualifications, many candidates still begin their academic careers in non-tenured positions. Achieving tenure typically requires evaluations based on teaching effectiveness, research publications, peer reviews, and the ability to secure research funding through grants.

Dhaka University, the oldest and most prestigious university in Bangladesh, still adheres to a recruitment process that has changed little over the past century. Even today, SSC and HSC results are scrutinised, and teachers are appointed through a single interview after obtaining a master's degree.

In contrast, universities worldwide follow far more rigorous and competitive hiring processes. For instance:

1. Interested candidates submit their CVs, cover letters, teaching philosophy statements, research statements, transcripts of their honours, master's, and PhD degrees, publication lists, and any previous teaching evaluations.

2. A search committee (equivalent to a recruitment board) shortlists eight to ten top candidates for each position.

3. Online interviews are conducted with these candidates (via platforms like Zoom or Skype), and the top three to four candidates are invited to the campus.

4. On campus, candidates deliver demonstration classes and research presentations.

5. The search committee conducts individual interviews with the candidates.

6. Department chairs, deans, and the university's vice-chancellor or pro-vice-chancellor engage with the candidates for further evaluation.

7. The search committee prepares a report analysing the strengths and weaknesses of each candidate, ranks them, and submits the findings.

8. The university then extends an offer letter to the most suitable candidate for the position.

This rigorous process ensures that the best talent is recruited. By contrast, Dhaka University's outdated and oversimplified recruitment process risks compromising the quality of education and research.

On 1 January this year, we celebrated the 131st birth anniversary of Satyendra Nath Bose. To mark the occasion, the Satyen Bose Club of Jagannath Hall organised a seminar, where I, along with Professors Golam Dastagir Al Qadri and Ratan Chandra Ghosh, delivered lectures. Additionally, the students of Dhaka University's Department of Physics hosted a day-long programme on 4 January. We should have celebrated this day nationally, for Satyen Bose demonstrated that world-class research is possible in this part of the world, despite challenges and limitations.

Kamrul Hassan is a professor in the Department of Physics at the University of Dhaka.

Comments