We need a permanent health commission

The Daily Star (TDS): Can you briefly outline the evolution of the health sector in Bangladesh?

Liaquat Ali (LA): The First Five-Year Plan (1973–78) of Bangladesh was entirely focused on the public sector, with health development prioritised in rural areas over urban centres, particularly in terms of infrastructure. Until 1980, the private healthcare sector in Bangladesh remained relatively underdeveloped. However, the following decade saw increasing commercialisation across various industries, including healthcare. The private sector chose to invest in more profitable secondary and tertiary care rather than primary healthcare. As a result, the private sector now controls nearly 70 percent of the market share.

Ongoing neglect has further weakened the public health sector. Over the past two decades, its share has declined from 38 percent to 23 percent. The Health Care Financing Strategy 2011–12 aimed to improve health financing in Bangladesh. At the time, out-of-pocket expenditure was 64.5 percent, with a target to reduce it to 40 percent by 2030. However, instead of decreasing, this figure has now risen to over 70 percent, increasing the financial burden on citizens.

TDS: How do you evaluate the health sector's budget allocation?

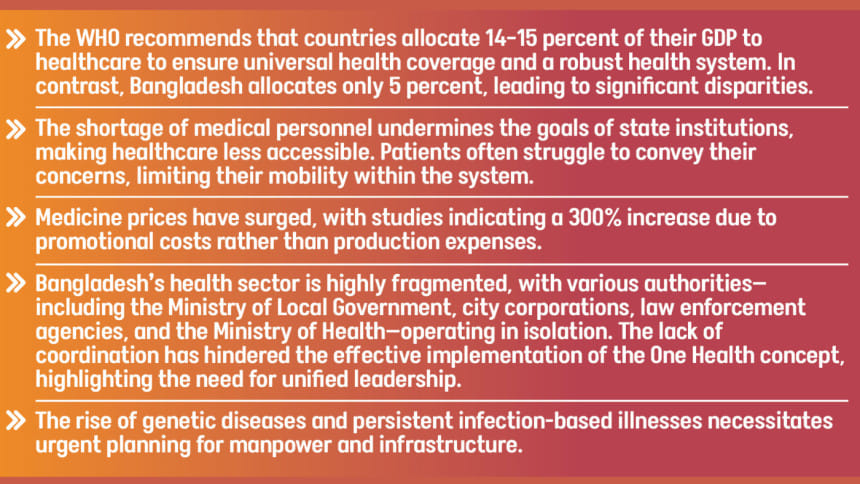

LA: While the public health sector has seen an increase in absolute budget allocation, its share as a percentage of GDP remains insufficient. The WHO recommends that countries allocate 14–15 percent of their GDP to healthcare to ensure universal health coverage and a robust health system. In contrast, Bangladesh allocates only 5 percent, leading to significant disparities.

Mismanagement in healthcare governance and financing has contributed to the sector's current state. At the policy level, forward-thinking reforms have been obstructed. Thus, a multifaceted approach is necessary to address the challenges we face.

TDS: What are the key challenges in balancing healthcare workforce distribution between urban and rural areas?

LA: The shortage of medical personnel undermines the goals of state institutions, making healthcare less accessible. Patients often struggle to convey their concerns, limiting their mobility within the system. At the upazila level, doctors face an overwhelming patient load, resulting in inefficiencies and an overburdened system.

Bangladesh's availability of medical personnel does not meet WHO standards, which recommend a doctor-to-population ratio of 44.5 doctors per 10,000 people, along with three nurses and five trained assistants per doctor. While there has been a recent increase in the number of nurses, the number of auxiliary healthcare personnel has declined. Proper healthcare management, including cleanliness and doctor-patient interactions, must be prioritised. Additionally, auxiliary healthcare workers in both metropolitan and smaller towns must play a more active role—an area that requires significant development.

A well-functioning referral system is essential in the medical sector. It facilitates the transfer of patients from one healthcare provider to another for specialised care or advanced treatment. However, deficiencies in our current system have led to an over-reliance on specialists, often bypassing the referral process entirely. Financial incentives have been prioritised over patient care, and within urban settings, primary healthcare remains highly disorganised.

It is worth questioning whether government plans in the 1970s adequately considered future demographic shifts. Contemporary challenges indicate that healthcare planning must be integrated, incorporating medical professionals and experts from various fields. For example, tackling the spread of dengue requires a multidisciplinary approach that extends beyond traditional healthcare.

In the 1980s, urbanisation in Bangladesh accelerated, with the urban population rising to around 15 percent by 1985, driven by industrialisation, rural-to-urban migration, and city expansions. As of 2025, approximately 41 percent of the population resides in urban areas.

Regarding the urban-rural divide, functional deficiencies are more prevalent in rural areas. However, government initiatives such as community clinics, union health centres, and upazila-level institutions have played a role in mediating these gaps, particularly in referral processes. On the other hand, in urban areas, a large proportion of the population bypasses the referral system entirely, contributing to inefficiencies in healthcare delivery. The shortcomings in urban planning serve as a stark reminder of our current realities. Moving forward, there needs to be a shift in awareness—one that does not place sole blame on medical practitioners but instead addresses systemic issues such as the absence of a well-structured referral system.

TDS: How does the current pricing of medicines and medical equipment impact accessibility and affordability in healthcare?

LA: Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury played a key role in formulating Bangladesh's National Drug Policy in 1982, aiming to make essential medicines affordable and promote domestic pharmaceutical production. This policy strengthened the local industry, reducing reliance on imports and eventually enabling exports.

However, despite these achievements, medicine prices have surged, with studies indicating a 300% increase due to promotional costs rather than production expenses. The shift from multinational to local dominance has not significantly benefited the masses, as drug prices remain high. Additionally, there is growing concern over excessive prescriptions, driven by industrial interests rather than medical necessity.

TDS: Is our medical personnel receiving adequate salaries and benefits?

LA: Doctors spend years acquiring expertise, yet their compensation does not always reflect their qualifications. The Bangladesh Civil Service (BCS) structure, within which many doctors operate, provides annual increments, but this may not be competitive internationally. Bangladesh needs to invest more to retain top talent. Financial, social, and regional factors must all be taken into account when addressing salaries, private practice, and professional dignity.

TDS: What is the current state of medical education in Bangladesh?

LA: Medical education is at the centre of shaping the future healthcare industry, influenced by both public and private institutions, economic and political forces, and various interest groups. In Bangladesh, the training of medical professionals, including doctors and nurses, often appears unstructured. Many institutions actively promote themselves as prestigious despite significant gaps in faculty expertise, infrastructure, and manpower. The issue is not with students but with the need for comprehensive development—strengthening medical education, ensuring quality accreditation across all institutions, and addressing workforce shortages.

TDS: What steps can be taken to improve preparedness for future pandemics?

LA: Preparedness is critical as climate change and environmental crises continue to threaten public health. The rise of genetic diseases and persistent infection-based illnesses necessitates urgent planning for manpower and infrastructure. Contact tracing and isolation, essential public health strategies, must be systematically implemented. For instance, if a virus is reported in China, Bangladesh must be ready for cross-border transmission with buffer manpower and infrastructure. Currently, the medical sector faces significant workforce shortages, highlighting the need for systemic reforms in emergency response, border screening, and vaccination access.

Bangladesh's health sector remains fragmented, with multiple authorities—such as the Ministry of Local Government, city corporations, law enforcement agencies, and the Ministry of Health—operating in silos. The One Health concept has struggled due to a lack of unified leadership. Establishing a permanent health commission could provide the necessary oversight, ensuring coordinated policies, fair pricing of medicines, and a more resilient healthcare system.

The interview is taken by Priyam Paul

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments