The Quiet Horror of "Less-Lethal" Repression

Imagine a weapon so "magical" it allows a regime to crush dissent without creating martyrs. A device so surgically cruel that it disables without killing. It leaves no corpses, no funerals, no international headlines. Just silence, trauma, broken dreams, and ruined lives. For authoritarian regimes, this is more than just a tool; it's a "eureka" weapon. In Bangladesh, that weapon has a familiar name: the pellet gun, or chhorra guli.

In the hands of the Awami League regime, chhorra guli became the state's preferred instrument of repression. During the July–August 2024 mass uprising, it was deployed for a precise purpose: not to kill, but to maim. Marketed deceptively as "less-lethal," these weapons blinded protesters, shredded limbs, and psychologically shattered an entire generation. The pellet gun doesn't provoke martyrdom or backlash. Instead, it manufactures social death—physically broken, economically ruined, politically erased. No coffins, just crutches. No heroes, only trauma. It is violence with plausible deniability, repression dressed as "restraint."

This is what makes the pellet gun so appealing to autocrats: it looks "humane" on paper but performs like a calibrated instrument of terror on the ground. It is a weapon that mutilates while masquerading as mercy.

This piece traces that contradiction. Through survivor testimonies, medical evidence, and political theory, we expose the "less-lethal" lie. The pellet gun is not just a tool for crowd control or riot management; it is a weapon of silence, suffering, and state-sanctioned amnesia.

Bodies That Survive, Lives That Don't

During the 2024 mass uprising, the Bangladesh government's preferred weapon for crowd control was not tear gas or lathi charges; it was the pellet gun. Marketed as "less-lethal," this weapon became a frontline tool in a campaign of deliberate mutilation carried out by law enforcement. According to the 2025 UN OHCHR fact-finding report, 736 civilians were treated for pellet-related eye injuries at the National Institute of Ophthalmology in Dhaka, with 504 requiring emergency surgery. In Sylhet, the Osmani Medical College Hospital handled 64 metal shot injuries, 36 of which were to the eyes. These were not warning shots or accidents. They were targeted acts to disable, terrify, and permanently incapacitate.

Sapran, a human rights think tank, conducted a study on the deployment and aftermath of pellet guns titled Deadly in Disguise: The Use of Pellet Guns Against Civilians During the July–August 2024 Mass Uprising in Bangladesh. Drawing on testimonies from survivors and frontline doctors, our findings expose a system designed to produce suffering while avoiding accountability.

For example, Mainuddin, a father of three and the sole breadwinner of his family, shared:

"My eldest daughter is a 9th grader. I have two elderly parents who need me. But I've lost my job. My family now takes care of me, I'm bedridden, and we have no income. How do you think I'm doing mentally?"

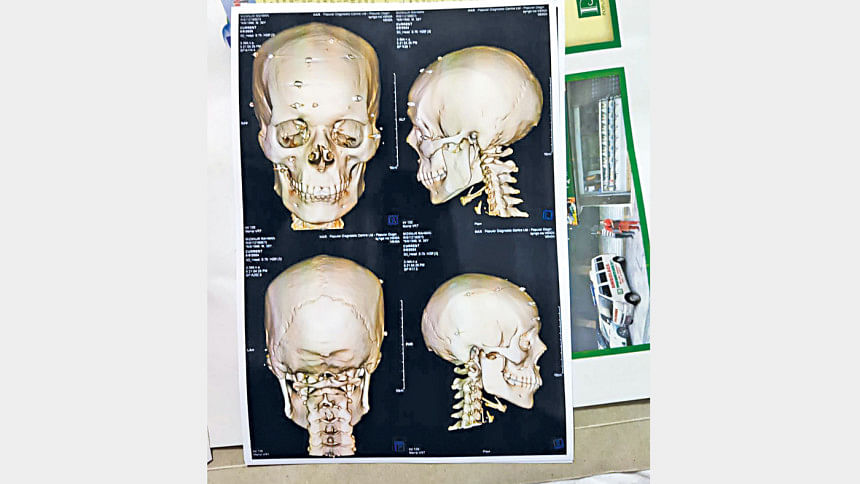

One particularly harrowing case is that of 23-year-old Khokon Chandra Barman, shot in the face from very close range during the 5 August 2024 massacre outside the Jatrabari Police Station. His injuries completely obliterated his upper lip, nose, palate, and gums. The Health Ministry, under the Interim Government's guidance, arranged for the initial phase of his advanced reconstructive surgery in Moscow last May. Khokon described his experience of seeing the Jatrabari police indiscriminately shoot civilians during a media interview:

"The police came out of the Jatrabari Station and fired at us like we were birds." He added, "They didn't fire to disperse us, they fired to destroy us."

Khokon's life will never be the same again. Today, he lives with profound disfigurement and permanent nerve damage—a living testament to the irreversible physical damage metal pellets can cause to the human body.

For others, the psychological damage is accompanied by intense survivor's guilt. Sajjad, a high school student, mourned:

"It would've been better if I died… The doctors say maybe in three years I can lift a cup with this hand. But I can't even hold anything now. What kind of life is this?"

The physical toll is severe. Many victims underwent multiple surgeries, and in most cases, doctors were unable to remove all the pellets from their bodies. The remaining metal fragments became a permanent internal health hazard, causing chronic infections, nerve damage, or future health crises. One doctor described these fragments as "a permanent source of mental and physical suffering."

Young people were disproportionately targeted. Doctors expressed alarm at treating victims as young as 10 or 12 years old. Female patients were reported to exhibit even greater psychological distress. Many suffered not only physical pain but also intense shame, isolation, and long-term trauma.

The story of Himel, a young protester from Tangail, is particularly disturbing. Shot from the second floor of a local police station while trying to secure the release of detained students, he now carries 300–400 pellets in his face and neck.

"I can no longer see with either eye," he said. "All the pellets are still inside me."

Another victim, Raisul Rahman Ratul, a college student, was shot after Friday prayers in Azampur, Uttara. As he tried to talk to the police, he was grabbed and shot at point-blank range in the abdomen. He underwent multiple surgeries, but only 45–50 pellets out of 250 could be removed. Fifty-five percent of his abdomen was surgically excised.

"My kidneys are damaged. I'm in pain all the time. I was supposed to take my HSC exams this year. Now I can't even prepare."

Abdullah, a high school student from Enayetpur, missed months of school due to pellet injuries. His mother shared:

"He was supposed to move to 9th grade, but he's still in bed. Doctors say he might never walk again."

Sajjad, another teenage victim from Natun Bazar, described: "This arm still hurts… I can't even carry my school bag. My mum carries it for me now."

These testimonies reflect a coordinated strategy to maim instead of kill, to neutralise protesters without creating martyrs.

One interviewed human rights activist emphasised that this is not merely a failure of law; it is the result of deliberate policy. Despite existing legal frameworks requiring proportionality and regulation in the use of force, pellet guns were deployed indiscriminately and without oversight.

This is why the state prefers pellet guns: they represent a politics of invisible cruelty. They are not merely weapons of law enforcement; they are instruments of authoritarian governance calibrated for modern optics. These testimonies lay bare what statistics and reports often obscure. Pellet guns are not "less-lethal." They are intentionally crippling. They create a landscape of broken bodies, abandoned families, and silenced dissent.

Maiming as Governance Across the World: The Hidden Strategy Behind Pellet Guns

The use of pellet guns by authoritarian regimes is a deliberate strategy. This is violence rebranded, refined, and made palatable to a public conditioned to equate state brutality with death alone. As political theorists like Jasbir K. Puar and Achille Mbembe argue, the power of the modern state lies not only in its capacity to kill, but in choosing who suffers, for how long, and how silently.

Puar's theory of the "right to maim" shows that states increasingly choose injury over execution. A dead protester can become a martyr, a rallying cry—but a blinded or paralysed student becomes a burden: forgotten, disempowered. Pellet guns produce precisely this kind of injury—one that incapacitates but does not inspire.

Mbembe's concept of necropolitics sharpens this insight: pellet victims are kept biologically alive but rendered socially dead. Unable to study, work, or participate, their prolonged survival becomes a condition of extended suffering. These are not collateral damage; they are calculated acts of repression. Maimed bodies in hospital beds, blindfolded eyes, shattered limbs—these become silent warnings to society: "This is what happens when you resist." And because these injuries are less visible than coffins and funerals, they often escape both national outrage and global condemnation.

However, Bangladesh is not the only country where pellet guns have been used by the state to repress dissent. From authoritarian regimes to so-called "liberal democracies," their deployment reveals a global pattern of state violence masked as "restraint." In Indian-administered Kashmir, over 6,000 people were injured by pellet fire in July 2016 alone, many permanently blinded, including children and bystanders. Iran's security forces deliberately targeted the faces of women and students during the 2022 "Women, Life, Freedom" protests. In Palestine and Lebanon, Israeli forces employed pellet-like projectiles to maim civilians, including health workers and children, under a strategy designed to disable resistance without mass death.

Chilean protests in 2019 left over 400 protesters with eye injuries; U.S. law enforcement used similar weapons during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, resulting in over 115 cases of severe trauma. From Bahrain to Egypt, pellet injuries have been met with impunity, not reform. These cases underscore a transnational logic: to harm without killing, suppress without scandal.

In this global matrix of repression, pellet guns thus serve a double purpose: they enforce control while minimising accountability. They do not reduce violence; they optimise it for deniability. And in doing so, they expose the cruel genius of modern authoritarianism: the ability to break bodies while claiming restraint.

Legal Contradictions and the Crisis of Conscience

The deployment of pellet guns during the 2024 mass uprising was not just a humanitarian catastrophe; rather, it was a legal and moral collapse. Although numerous domestic laws, constitutional safeguards, and international agreements are in place to regulate the use of force, the state ignored these protections and used force without accountability, disregarding the basic principles of lawful, proportionate, and responsible policing. Both national and international laws clearly state that force should only be used when absolutely necessary, applied in a measured way, and only after all other options have been exhausted. Yet, for many protesters and bystanders, pellets were the first response. Victims, including children and passers-by, were shot at point-blank range without any warning, often in the face, chest, or abdomen. This conduct blatantly violated the right to life and protection from torture under the ICCPR (Articles 6 and 7), the Convention Against Torture, and also breached the standards outlined in Police Regulation Bengal 1943 (PRB 153C).

These were not isolated accidents. The injuries, blindness, amputations, and embedded shrapnel were systematic, widespread, and predictably catastrophic. As such, they are not mere excesses but evidence of premeditated, unlawful violence, in direct breach of the UN Guidance on Less-Lethal Weapons (2020) and the domestic laws of Bangladesh.

The damage went far beyond physical wounds. Many young survivors were emotionally traumatised, yet the Hasina government offered no support. Financial burdens increased as some lost their jobs, others had to quit school, and many fell into heavy debt just to pay for their medical care. Despite causing this suffering, the regime provided no compensation, no medical assistance, and no help to rebuild their lives, failing both its responsibilities under international law and its constitutional duty to protect human dignity.

Healthcare professionals were placed in an ethical crisis. Moreover, numerous victims fled medical facilities to evade surveillance or retaliatory actions, thereby infringing upon Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which guarantees the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. The obstruction of access to medical care and the intimidation of healthcare providers constitute violations of this right. Such actions further breach Article 3 (right to life, liberty, and security of person) and Article 5 (prohibition of torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Concurrently, activists and journalists documenting these abuses were subjected to harassment, surveillance, and silencing tactics. The intent extended beyond inflicting physical harm to include the deliberate destruction of evidence.

The legal framework exists but has been hollowed out, bypassed, and weaponised. The result is a country where violence is normalised, law is ornamental, and justice remains out of reach for the wounded, the abandoned, and the silenced.

From Silence to Ban

The use of pellet guns during the 2024 uprising was a deliberate authoritarian strategy to crush the people's resistance without triggering the global outcry that mass killings might. These weapons may not always kill, but they kill futures, destroy bodies, silence movements, and normalise state violence. In defiance of international law and Bangladesh's own constitutional commitments, pellet guns have been used to blind children, disable workers, and silence youth. This is not restraint, but calculated repression—violence masked as discipline.

We must reject the myth of "less-lethal." There is nothing less harmful about a weapon that leaves people unable to walk, study, or see. Pellet guns are not tools of order; they are tools of institutionalised mutilation.

It is time to call pellet guns what they truly are: state-sanctioned weapons of maiming and fear. To allow their continued use is to accept repression as policy.

We must urgently, and unequivocally, demand a permanent ban on pellet guns in Bangladesh.

Md. Zarif Rahman is a member and student representative of the Police Reform Commission and currently serves as the research lead at Sapran, a human rights organisation. Zeba Sajida Saraf and Nusrat Jahan Nisu work as research assistants at Sapran.

Comments