"If properly planned, even now, Dhaka can be transformed into a very decent, liveable city. We can take advantage of the river, the khals, the lowlands, and the richness of the soil for the growth of trees and plants. But this presupposes that there should be a pride in our capital city, with the people participating consciously in the growth process."

— Muzharul Islam, 1983

Cities around the world experienced phenomenal growth during the 20th century and became an important topic of architectural discourse. Visionary thinking by leading architects of this period contributed to the development of ideas about the urban future of the world. Bangladesh, being a densely populated country, experienced rapid urban growth in the last quarter of the 20th century after it emerged as an independent state. This was largely because the country had remained predominantly agrarian during both the colonial period and the postcolonial period under Pakistan. On the other hand, architecture in Bangladesh had a brilliant start immediately after the end of British colonial rule, thanks to a Bengali named Muzharul Islam, who was initially trained as a civil engineer but chose to become an architect.

Muzharul Islam singlehandedly contributed to the development of a vibrant architectural scene for over five decades since the end of British colonial rule in 1947 in this part of the world. His architectural works exemplify a search for a place-specific modern architecture, and his activism records his pursuit of establishing a modern and progressive culture of nation-building, using architecture and physical planning as key tools. From the early 1950s to the mid-1970s, Muzharul Islam actively responded to the demands of his professional practice as well as his commitments to nation-building. The tragic event of the assassination of the Father of the Nation, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in 1975, brought an abrupt end to his efforts, and after a break of almost five years, he was able to return to his work, though not with the same vibrancy as before.

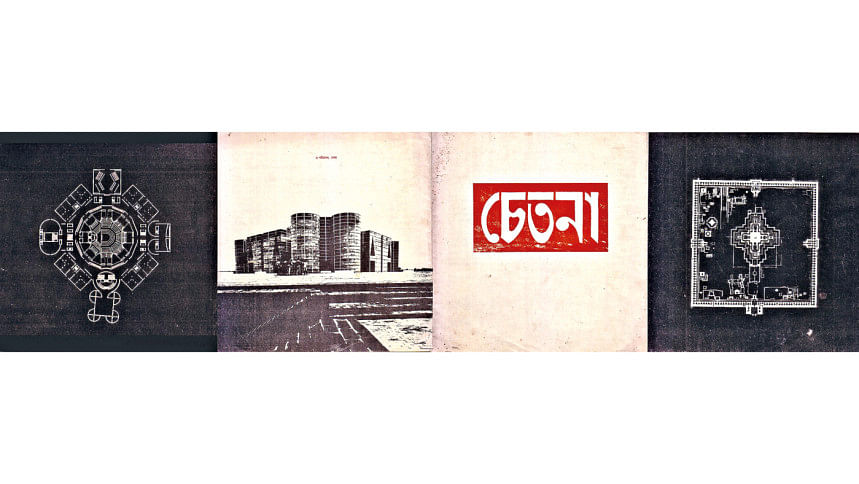

In 1975, he was in his early 50s, and it was a great loss for Bangladesh that the exceptional intellectual and creative ability of Muzharul Islam could not be fully utilised in the post-1975 period due to his political beliefs. Thanks to a few well-wishers, he was able to maintain a skeletal practice during this unfavourable time in his life. This was, without doubt, meagre for a person of his calibre, but it nonetheless allowed him to continue, albeit on a much-reduced scale. On the other hand, an important development in the early 1980s—namely, the formation of an architectural society called Chetana—kept him actively engaged with architecture and urbanism, providing a much-needed impetus for continuing with his ideals. In fact, this engagement significantly impacted the development of architectural culture in Bangladesh in the years that followed.

Chetana Movement

The formation of Chetana in the early 1980s was a unique event in the context of the postcolonial and post-independence architectural history of Bangladesh. Chetana played a prominent and crucial role in the development of architectural discourse that provided new direction to the architectural culture of Bangladesh in the 1980s and 1990s. To gain a comprehensive understanding of this role, it is important to recount the origins and activities of Chetana.

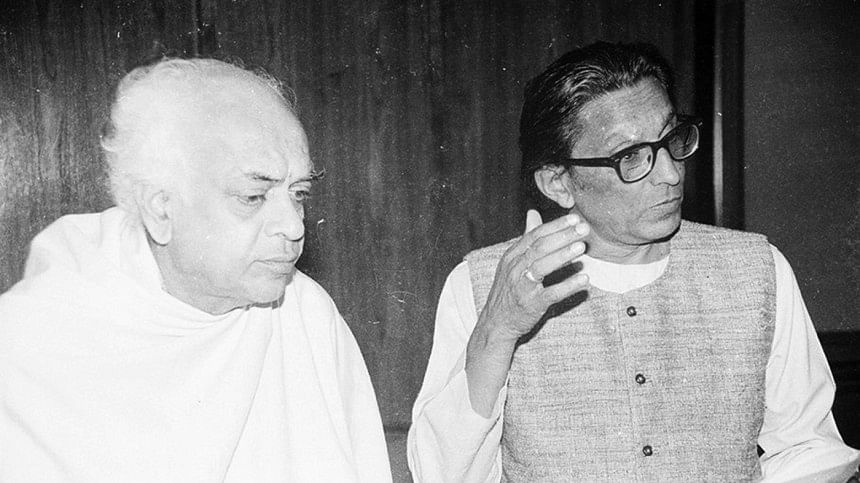

Chetana began as an initiative of a small group of young architects who gathered around Muzharul Islam—the well-known architect of Bangladesh at the time—with the simple objective of learning from him. At first, the group had no name; the naming of the group as Chetana occurred much later. The formation of Chetana emerged from a simple but important realisation by its members: that Islam, while being an accomplished architect with an illustrious career, was absent from architectural education in the country. It was indeed puzzling to them that Muzharul Islam remained distant from the only architecture school in the country. Another incomprehensible fact was that his practice was almost without any work at that critical juncture in his career. The young architects found it difficult to reconcile these facts with the stature of Muzharul Islam.

The group of young architects who initiated this study circle met Muzharul Islam in the winter of 1981 and requested him to conduct design classes. Islam was initially reluctant to get involved but eventually agreed after much persuasion. It was not until the summer of 1982 that the classes began at his studio-cum-residence in Paribagh, Dhaka, and within a very short time, a few senior-year students also joined. A seminar format was adopted for this learning programme, with the group meeting twice a week for Islam's lectures on the design process. Islam was quite emphatic about the process being one directed towards producing what he called "decent" architecture. By the time Islam's series of lectures concluded, the group found the entire process highly rewarding and inspiring, and wished to continue this learning journey in some form. Observing the group's enthusiasm, Islam suggested that they choose a book from his library and begin a reading and discussion programme as a way of continuing.

The reading and discussion sessions continued with one book after another, including seminal texts on modern art and architecture movements in Europe and America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Islam's lectures on the design process, along with the subsequent readings and discussions by the group members, took place over just a few months; yet the enriching experience generated a strong desire to continue the journey. At this stage, the group felt the need to shift the focus towards the history, society, and culture of Bangladesh, where most of the members were expected to work.

This phase of activities began with inviting eminent personalities of the country from different fields of culture to give lectures to the group. The topics included History, Language, Literature, Visual and Performing Arts, Town Planning, and Archaeological and Architectural Heritage. The group was privileged to listen to the lectures, as most of the speakers enjoyed close friendships with Islam. The lectures helped the members of the group to gain valuable insights into the culture of the country, enabling them to address issues that were pertinent to the specific context of Bangladesh. The eminent personalities who gave lectures at that time included Academician Kabir Chowdhury, Artist Quamrul Hassan, Archaeologist Nazimuddin Ahmed, Cultural Activist Wahidul Haque, Historian Muntassir Mamoon, Educationist Mohammed Moniruzzaman, Historian Momtazur Rahman Tarafdar, Historian Perween Hassan, and Thespian Aly Zaker.

The success of those programmes led the group towards an organisational structure and the naming of the group. After careful scrutiny of names suggested by the members, the group chose the Bangla word "Chetana" as the name. Chetana in Bangla means consciousness or awareness—a word quite appropriate to the group's aspiration to fill the gaps in their knowledge. The naming led to the group's formal emergence, which took place in an event with a presentation of a manifesto and declaration. While manifestoes and declarations abound in modern architecture movements in the West, and also among political parties in the country, for an architectural group from Bangladesh, this was a unique initiative. This was surely a sign of directing the activities towards a movement. Drafted jointly by the members, the manifesto called for an architecture firmly rooted in place as well as connected to universal aspirations. The manifesto was not only signed by the architect members but also by noted personalities of the country, including poets, writers, painters, thespians, musicians, historians, and archaeologists.

An important opportunity to connect with the international architectural scene opened up for the group through the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, initiated in 1977, via Muzharul Islam, who was a member of the first jury of the award. Islam's involvement facilitated conversations and connections with architects, architectural historians, and leading thinkers from different parts of the world, and as a consequence of this contact, the Aga Khan Award for Architecture proposed holding a regional seminar in Dhaka involving both regional and international architects.

This led to the seminar "Regionalism in Architecture" in Dhaka in December 1985, which was a major event for architecture in Bangladesh. Leading architects, architectural historians, and thinkers of the region and other parts of the world participated in this landmark event, and for the members of Chetana, this was a significant occasion as they were able to listen to historians like Kenneth Frampton and William Curtis, and architects like Paul Rudolph, Charles Correa, and Geoffrey Bawa, among others. Muzharul Islam, Kazi Khaleed Ashraf, and Saif Ul Haque presented two papers on behalf of Chetana—one discussing the particular context of Bangladesh's architecture and the other exploring the role of government in architecture.

The Aga Khan seminar motivated Chetana to organise a seminar with Balkrishna Doshi of India, who had missed the 1985 seminar. In the spring of 1987, Chetana organised a seminar in Dhaka on architectural design and education, which was attended by Doshi, Anant Raje, Satish Grover, and Razia Grover from India. The successful organisation of the seminar surely exhibited an enhanced capability of the group in conducting such events and provided further impetus for expanding its activities.

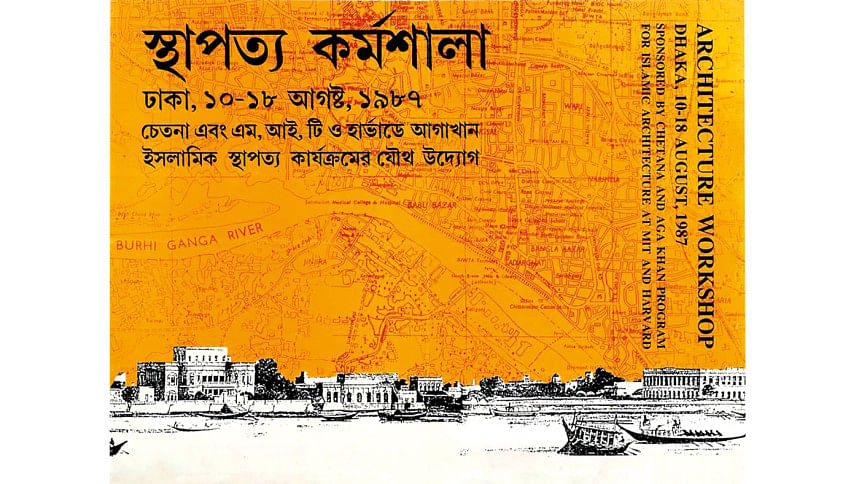

In the summer of 1987, a workshop on the city of Dhaka—comprising a design charrette for students of architecture, and a design workshop and presentations for architects—was organised by Chetana. Sketch proposals were prepared by participants of the workshop for four different areas of the city: the historic riverfront, the colonial civil station, the postcolonial New Market area, and the civic sector of Louis Kahn's Sher-e-Banglanagar. The workshop also included presentations by the Capital Development Authority, visiting scholars, and, most importantly, Muzharul Islam, who shared his visions for future Dhaka. Islam had long voiced his concerns regarding the unplanned development of the city, and the workshop provided him with the opportunity to present his ideas, along with drawings elaborating strategies for a planned development of Dhaka that would give due consideration to the particular topographical conditions of this deltaic city.

Within this short period of formation, the members of the group also started writing and publishing on architecture. The manifesto, programme announcements, flyers, brochures, posters, and newsletters established a distinct style of graphic design that ranged from photocopiers to printing presses. Another important development during this period was the dissemination of information abroad on architecture in Bangladesh. A cover story on Bangladesh's architecture featured in the Indian magazine Architecture plus Design in 1988, written and compiled by Saif Ul Haque, and an essay by Kazi Khaleed Ashraf was published in Mimar in 1989 from Singapore. The group by that time had gained sufficient confidence to embark on programmes of far greater ambition, and in 1989, it launched a programme to document principal monuments of Bangladesh with the objective of creating materials for the study of architecture in the country.

To undertake this task, the group transformed its organisational structure into a formal entity of a registered society, and the name changed to Chetana Sthapatya Unnoyon Society (Chetana Architecture Development Society), with a shorter version as Chetana Society. While the work on the documentation project required considerable involvement from the group, the activities of lectures and discussions continued in parallel. In 1996, a major seminar on architecture entitled "Dialogue on Design" was organised by Chetana, which brought together established and emerging practices to share their work with architects, students, and the general public.

In December 1997, the documentation programme titled Sthapatya Bangladesh (Architecture Bangladesh) culminated in the holding of the exhibition Pundranagar to Sherebanglanagar: Architecture in Bangladesh. The exhibition venue was the National Museum in Dhaka, which drew visitors from all corners of the country, and a book with the same title was published on the same occasion. The exhibition received extensive coverage from radio, television, and the print media. While the exhibition was a momentous occasion for Chetana, an unexpected and tragic event befell the group with the untimely death of Raziul Ahsan, the General Secretary of the society, in a car accident. Ahsan's sudden death was a huge loss for the society, which was by then well positioned to undertake greater responsibilities towards the development of architecture in Bangladesh. The work of the Sthapatya Bangladesh project was a strenuous one for the society, and the death of Raziul Ahsan created a vacuum that was difficult to fill, and the society was showing signs of slowing down.

Even in that challenging situation, a few programmes were undertaken. A workshop on the historic riverfront of Dhaka and another on heritage photography took place in 1999, but by the year 2000, it became clear that the society had lost much of its organisational capability to continue with further programmes. Muzharul Islam was nearing the age of eighty, and many of the founding members were occupied with their careers. By 2001, the society had become largely inactive. The nearly two decades of its dynamic existence merit being considered as a movement in architecture in Bangladesh that brought vitality to a lacklustre architectural scene—like activating a moribund river with flow. Although Chetana ceased to continue, the vision of an architecture that it nurtured was to find its way into the architectural scene of Bangladesh and beyond, through works, writings, and discussions.

Beyond Chetana

The impact of the Chetana movement is visible in the works of many architects active in practice as well as in teaching. The body of works and writings coming into existence is indicative of a new beginning in architecture in Bangladesh. Chetana and the significance of architecture in Bangladesh are receiving recognition both within and outside the country. In December 2017, a major exhibition on architecture in Bangladesh opened at the Swiss Architecture Museum in Basel, which later travelled to Bordeaux in France and Frankfurt in Germany, and the story of Chetana is a prominent part of that exhibition. The history of architecture is a history of many developments in many different locations and times. The emergence of the Chetana Society in Bangladesh and its efforts towards new architectural thinking in the context of Bangladesh constitute one such development and an architectural movement. A movement depends on the gathering of forces with the will for change at a particular juncture in time. For the Chetana movement, the gathering of young architects with their student compatriots and Muzharul Islam was that force at the juncture of the 1980s.

At that time, there were around 200 architects and one school of architecture in a country with a population of around 80 million. Today, Bangladesh has over 5,000 architects, nearly 30 schools of architecture, and a population of around 170 million people. Although the ratio of architects to population has improved, the reach of architects remains confined to a very select group of people. The increasing number of architects and schools of architecture are positive changes, but to make architecture accessible to the vast majority of people and to address existing and emerging challenges, a far greater movement is required—a movement for revolutionary change in the way we learn and produce architecture.

Saif Ul Haque is an architect practising in Dhaka.

Comments