Managing the mountain: Dhaka’s residential waste crisis and the search for solutions

In the sprawling, ever-expanding metropolis of Dhaka, where over 20 million people live within a congested urban sprawl, one crisis grows as visibly and relentlessly as the city itself: waste. Every day, Dhaka generates approximately 6,000 tonnes of solid waste—a figure that is steadily rising as urbanisation accelerates. From the gleaming towers of Gulshan to the narrow lanes of Mohammadpur, managing this waste is a daily battle. Yet amid the mounting challenge, sparks of innovation and community action offer hope.

Door-to-Door Collection: The Urban Lifeline

In many middle- and upper-income neighbourhoods such as Dhanmondi, Uttara, and Mirpur, door-to-door waste collection has become an essential service. Run through collaborations between city corporations, NGOs like Waste Concern, and local community groups, these services ensure that household waste is picked up daily in exchange for a modest fee, usually between Tk 30 and Tk 100.

Despite the growing reach of this system, challenges remain. Waste collectors often mix biodegradable and non-biodegradable rubbish, rendering household segregation efforts futile. Moreover, waste workers frequently carry out their jobs without proper protective gear or equipment, exposing them to daily health risks. The sight of waste being collected in bare hands and transported in open carts reflects the gap between policy and practice.

Composting: Growing Green Amidst Grey

Composting is emerging as a small but significant tool in transforming urban waste. In pockets of the city, such as Lalmatia Block D and parts of Banani, NGOs have introduced community composting projects. Households are encouraged to separate organic waste, which is then turned into compost for use in rooftop gardens or community green spaces.

While the success stories are encouraging, composting remains niche. The primary barriers include limited space, especially in apartment buildings, and low public awareness. Still, the visible benefits in neighbourhoods practising composting—greener spaces, reduced waste volume, and community engagement—point to its potential.

The Informal Sector: Dhaka's Invisible Recyclers

Perhaps the most underappreciated yet critical component of Dhaka's waste management ecosystem is its informal recycling sector. An estimated 120,000 waste pickers navigate the city's streets, landfills, and dumpsters, salvaging recyclables such as plastic bottles, paper, and metal. These materials are sold through a network of intermediaries to recycling factories, primarily located in areas like Badda, Jatrabari, and Keraniganj.

A 2023 BRAC study revealed that informal recyclers divert nearly 15% of Dhaka's waste away from landfills. However, their work is often hazardous, unregulated, and socially stigmatised. NGOs such as Grambangla Unnayan Committee are now working to organise these workers into cooperatives, providing them with safety equipment, health check-ups, and legal identity cards—a first step towards recognition and dignity.

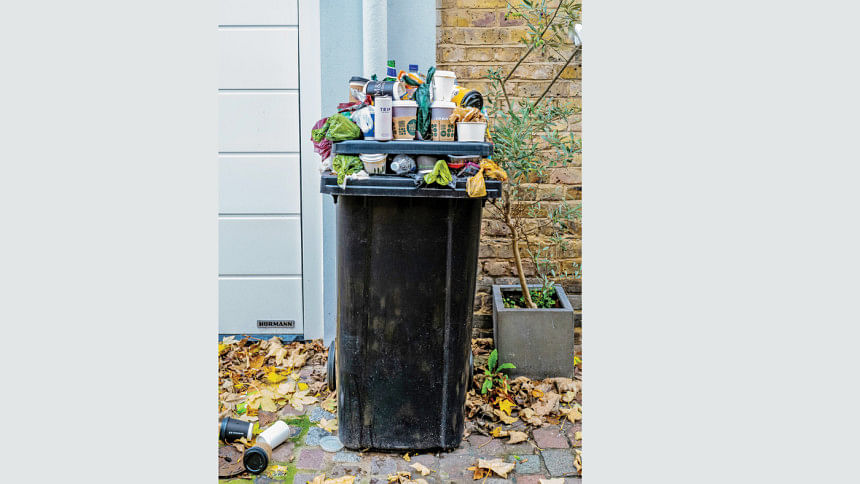

Community Bins: A Solution with Shortcomings

In areas where door-to-door collection is unavailable, community waste bins serve as the primary disposal method. Found in places like Shyampur, Kamrangirchar, and parts of Old Dhaka, these large bins provide a communal drop-off point for household waste.

However, the community bin system is fraught with problems. Irregular waste collection often leads to bins overflowing, emitting foul odours, attracting pests, and posing health hazards. Without community engagement or effective monitoring, these bins quickly deteriorate into neighbourhood eyesores rather than solutions.

Digital Disruption: Waste Meets Technology

Technology is slowly but steadily reshaping Dhaka's waste landscape. Start-ups such as GarbageMan and BD Recycle are offering app-based waste pickup services, specialising in the collection of recyclables and e-waste. Users can schedule pickups with a few taps on their phones, and the collected materials are processed through formal recycling centres.

In wealthier neighbourhoods like Bashundhara, Baridhara, and Gulshan, a few apartment complexes have adopted smart bins equipped with sensors that notify cleaning staff when the bins are full. While still in their infancy and confined to affluent communities, these digital innovations hint at a smarter future for waste management.

The Structural Gaps: A System Under Strain

Urban planners and environmental experts warn that despite some progress, the city's waste management system remains deeply fragmented. Dr Adil Mohammad Khan of Jahangirnagar University notes, "While roughly 50-60% of waste is collected regularly, about 40% of Dhaka's wards lack structured systems. Uncollected waste clogs drains, contaminates water, and fuels disease outbreaks."

Secondary transfer stations, which serve as interim points before waste reaches landfills, often operate inefficiently. The city's main landfill at Matuail struggles with outdated waste disposal techniques, resulting in leachate seepage that pollutes groundwater and exacerbates flooding during monsoon seasons.

Even ambitious projects like the proposed Waste-to-Energy (WtE) initiative, in collaboration with Chinese firms, face hurdles. Dhaka's waste has high moisture content, making incineration inefficient. Environmentalists are also concerned about the absence of proper impact assessments.

A Neighbourhood-Based Blueprint for Change

Experts like Khondaker Md Ansar Hossain from the Bangladesh Institute of Planners argue for a decentralised model. His research suggests that applying the principles of Reduce, Reuse, Recycle (3R), along with localised waste processing, could dramatically improve outcomes.

Using Dhanmondi as a hypothetical case study, he envisions micro-waste management facilities within communities. A three-acre facility could process 40 tonnes of waste daily through composting, recycling, and safe disposal. Organic compost could be marketed, generating revenue, while plastic and paper recycling could be streamlined, reducing landfill reliance.

Such a model, supported by government incentives and community ownership, could be adapted to neighbourhoods across Dhaka, balancing economic, environmental, and social considerations.

The Path Forward: Inclusion, Innovation, and Awareness

Dhaka's waste management story is one of contrasts: progress and paralysis, innovation and inertia. The way forward demands multiple, simultaneous interventions. Public awareness on waste segregation must be intensified. Composting and recycling need financial incentives. The informal sector should be formally integrated into municipal systems.

Ultimately, managing Dhaka's waste is not just about infrastructure—it is about mindset. A cultural shift towards responsible consumption, waste reduction, and shared responsibility is crucial. Only then can the city hope to transform its waste challenge into an opportunity for a cleaner, healthier, and more sustainable future.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments