On the path of dawn

Every moment of the night of 25 March 1971 and the following two months will always shine brightly in the depths of my memory. Even though I might not be able to express all those living memories in words, I will try to articulate a possible description of the events.

I remember my husband Tajuddin telling me on the day of the horrifying 25 March 1971, "Lili, none of you should stay home tonight, because I'm leaving, and Yahya's army has chosen a merciless path. I don't think it would be wise to take an unknown risk by staying at home tonight." He didn't say anything else. However, I couldn't leave the house on that terrible night.

It felt as if everyone could foresee the frightening consequences of the failed meeting and dialogue between Yahya and the leaders of the Awami League. But perhaps no one could truly imagine what was actually going to happen. A strange kind of eeriness hung in the air; it felt as if something ominous was about to take place. Relatives, friends, acquaintances, and even strangers crowded into our house to find out what the real news was. Many of them were leaving for safer places. By the time I had bid farewell to all of them, it was almost half past eleven at night. Yet despite a hundred doubts, I couldn't bring myself to step outside my house and go elsewhere.

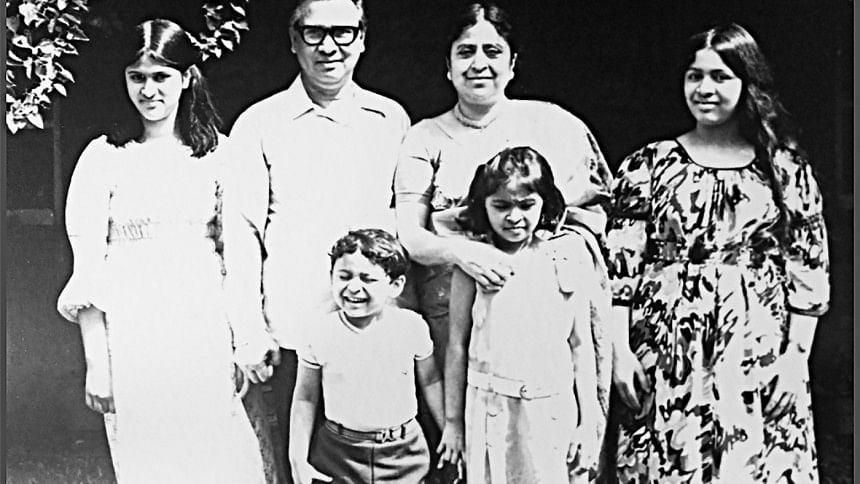

I had sent my elder daughter and her younger sister—Ripi and Rimi—and an adult niece who had come to visit us a few days earlier, to my elder sister's house in Tatibazar. My only son Tanjim, who was just over a year old at the time, and my five-year-old daughter Mimi were with me. I had thought that if I had to escape in a hurry, it would be difficult to manage with all of them; I might be able to slip away swiftly with just my youngest children.

On that dreadful night, Tajuddin left the house in a car with Barrister Amirul Islam; Dr Kamal Hossain also accompanied them. On the way, Dr Hossain got down at a relative's house in Dhanmondi. I later learnt that he was arrested by the Pakistani army a few days later. I was standing by a bush near the gate of our house, watching their car speed towards Road 15 in Dhanmondi, and then take a turn towards Lalmatia. Right at that moment, I heard the sound of bullets and mortar fire in the distance, and I immediately noticed several armed vehicles of the Pakistani army speeding along the road opposite our house, rushing towards Lalmatia. An unfamiliar fear gripped me at that time, but the very next moment I realised that Tajuddin had set out on a dark, dangerous journey to fulfil a great responsibility—and no matter how terrifying or gloomy the path, there was an invisible force guiding him unstoppably towards his destination. The speeding vehicles of the Pakistani army had lost their way. He had succeeded in eluding the army's reach. It was as if a divine manifestation of this event was unfolding within me.

Now I turned the focus back on myself, as I took a firm resolve to gather all my strength. Our house was two-storeyed; we used to live on the ground floor. Abdul Aziz and Begum Atiya Aziz lived as tenants on the second floor. Mr Aziz was from Kaliganj in Dhaka; he was a former vice-president of the Chhatra League. Over time, we had become very close. A few minutes after Tajuddin's car had departed, I took my two children and got into our car, instructing the driver to head towards Road 21, which lay opposite to our house, as quickly as he could. I intended to get down in front of any house there. I could see electricity and telephone lines being torn down, making a tremendous noise as they fell right in front of our gate. Just then, Aziz and Atiya almost leapt in front of us and stopped me from setting off. In a subdued voice, they said, "Bhabi, get down from the car without a moment's delay; the moment the car leaves the gate, it will be seized by the military." I immediately realised that the path of escape was blocked, but we couldn't stay in the house either. I quickly changed my mind. I got out of the car and, standing under the stairway, told Atiya, "I will go upstairs with you and pretend to be a tenant as well."

Thankfully, Atiya and I both knew Urdu well. We changed our appearance by putting on salwar-kameez. Atiya would sometimes wear this attire at home. Due to our height and overall appearance, we both looked like non-Bengalis, and this gave us hope that we might evade the clutches of the enemy.

Aziz bhai was also not supposed to be home that night, but unfortunately, due to Atiya's firm opposition, he was forced to stay back—an act that led to tragic consequences. He was captured by the Pakistani army and incarcerated in the cantonment for seven months, enduring near-death suffering, though he was ultimately released in an unimaginable and miraculous manner. I went upstairs, changed my clothes, laid my sleeping son and daughter on the bed in Atiya's bedroom, and stood by the window. The sound of gunfire and mortar shells drifted in from the distance. I saw that Atiya and Aziz bhai were arranging sleeping spaces on the sofas in the large hall room. But I thought it would be wiser for Atiya and me to stay in the same room. The sound of shooting gradually came closer. Atiya and I remained together in the room.

Neither of us spoke a word. I peeked through the curtains of the southern window, and an indescribable scene met my eyes—the entire sky in the south was splattered in red. It seemed the sky itself had disappeared into the red. I heard the sound of one vehicle after another, and it felt as though our entire house was surrounded by military forces. They were now truly entering the house, firing as they moved. Having heard Sheikh Saheb's call for creating a fortress of resistance, they perhaps assumed there were arrangements for defence and counter-attack in the homes of the leaders. Thus, they positioned themselves around the house, armed with the modern weapons of that time, moving forward in a cautious manner. I peeked out again to get a quick glimpse of the main road outside our house. Nothing appeared except for the vehicles of the Pakistani army and the occupying force.

Atiya and I decided to keep the door closed and stay inside the room. If they knocked or pushed, we would open it and confront them. But by that time, intense shooting had already begun downstairs. The occupying forces were destroying the doors, windows, and the thick wire fencing around the veranda, which had already come under shell attack. They went into every room searching for Tajuddin and me.

We were ready to face death with resolute determination. My father, a nephew, and my sister-in-law's son were downstairs. Sixty-year-old Barik Miya, the caretaker and gatekeeper of our house, unable to comprehend the full scale of the situation, had hidden in the bathroom of my father's room. One group of the occupying force tied their hands and shouted loudly, demanding to know our whereabouts. Another group—around 50 men—shelled the door to the stairway, breaking it into pieces and entering the veranda on the second floor. It felt as though some of them were even running across the rooftop. When a group of around 25 to 30 men pushed against our door with a tremendous noise, Atiya asked in Urdu, "Who's there?" and opened the door. Immediately, four to five army officers entered, taking position and pointing a small sten gun at our chests. In a stern voice, they asked in Urdu, "Where is Tajuddin? Which one of you is Mrs Tajuddin? You or you?" Meanwhile, the rest of the soldiers were firing relentlessly through the windows.

Atiya promptly replied in Urdu, "Where is Mrs Tajuddin here? You must be mistaken. All of us are tenants here—Tajuddin is our landlord. They live on the ground floor."

I was worried about a picture of me hanging on a wall downstairs; there was the possibility of getting caught if we were even slightly careless. My son was in my arms, and I concealed him slightly. Before Atiya could even finish her sentence, I said in a chastising tone in Urdu, "I had told you before not to rent a place in these politicians' houses. Finally, this is what is in our fate… Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji'un." Before I could end my sentence, the officer who had been asking questions quickly lowered his sten gun and, fixing his sharp gaze on us, accepted his mistake, saying, "We made a mistake. Please stay here without any worry. I don't need to ask anything else." Meanwhile, my five-year-old daughter Mimi woke up from her sleep. She clung to me in fright, but thankfully she did not speak in Bengali at that time. The officer patted my daughter's head and said to me, "Bibi, please go to sleep. You need not be scared of anything." After that, they left the room. Atiya also followed them.

A newly married couple—guests of Atiya—were sleeping in the next room. They had come to visit from Narayanganj in the evening. As it had got late after dinner, and it was risky to go out at night, they had decided to stay back and had gone to sleep. They awoke in shock at the dreadful noise of the door being pushed, and as soon as they opened the door in fright and stepped outside, an army officer ordered the gentleman in a stern voice to go with them. Immediately, Atiya said in a reprimanding tone in Urdu to the guest (who had recently joined Tolaram College as a lecturer), "Habib bhai, what kind of sleep were you in? These men were screaming so loudly, and yet it took you so long to open the door!" In response, Habib bhai's wife accepted their fault in Urdu in an apologetic tone. Immediately, an army officer said, "It's alright. You can go back to sleep." In an unthinkable twist, they both escaped.

Then they tied up Atiya's husband, both my nephews, and the elderly Barik Miya, and kept beating them while taking them to their car. Aziz bhai's nine-year-old nephew witnessed all of this while hiding from the army.

My father used to stay in a corner room downstairs. They went there and asked him various questions in a rough voice. My father was quite ill at that time; he could not even get out of bed. The main question in their interrogation was where Tajuddin and I were. A few of them suggested taking my father with them, but two of the officers were unexpectedly well-mannered. When they asked him to lie down again, it felt as if his illness had touched their hearts. Later, remembering this gesture of theirs, I felt it was nothing but a wolf in sheep's clothing. My father did not lie down expecting to be spared; he thought he would be shot the moment he did. He overcame his fear and replied to them in English, "President Yahya can best say where Tajuddin is." At that moment, my father also played his own part. While lying in bed, he recited a stanza of a timely and poignant poem by Sheikh Sadi in Farsi, and then translated its meaning into English for them. Even amidst such a tense situation with gunfire, they looked at one another's faces and left the room, saying "Assalamu Alaikum," leaving behind a bundle of rope in my father's room. When I saw it later, I guessed that the rope had been brought to tie up Tajuddin and take him with them. I have kept that rope with me, as it remains a small witness, should the history of the Liberation Movement ever be written.

After about two hours, when the invaders finally left, all of us seemed to have turned into stone. None of us moved an inch; not a word left our mouths. We looked around very carefully to ensure no one was still there. Atiya and I were alone upstairs, even though Habib bhai and his wife were in the next room with their door closed, and my father was alone downstairs. Every moment was spent in a state of terrifying anxiety. But there was nothing to be done.

At that intolerable moment, I felt a sharp sense of pride deep in my subconscious. Without even realising it, I was confronted by a heart-wrenching question—how strange is the human mind! Tajuddin did not say a word before leaving; he didn't even point towards any direction. That night, at around 10.30 pm, he returned home with Mr Samad and Mr Mohaimen. Amidst the urgency, I noticed the faces etched with worry. There were many others with them. All of them left almost immediately. I saw him strolling around the garden without saying a word to me; I felt as if he would leave right then. Just about then, Barrister Amirul Islam and Dr Kamal Hossain arrived at our house. They left shortly afterwards. On his way out, Tajuddin almost ran to me and asked for a small towel. At the final moment, nothing was said. He simply left me in the midst of danger. How was this possible? I found the answer to that question later. The rights of over seventy million people were shining luminously in the glow of his decision at that moment; his wife and four children were lost amidst this.

This was the first article in the series titled Udoyer Pothe, written by Syeda Zohra Tajuddin. It was published in Dainik Bangla on 12 December 1972.

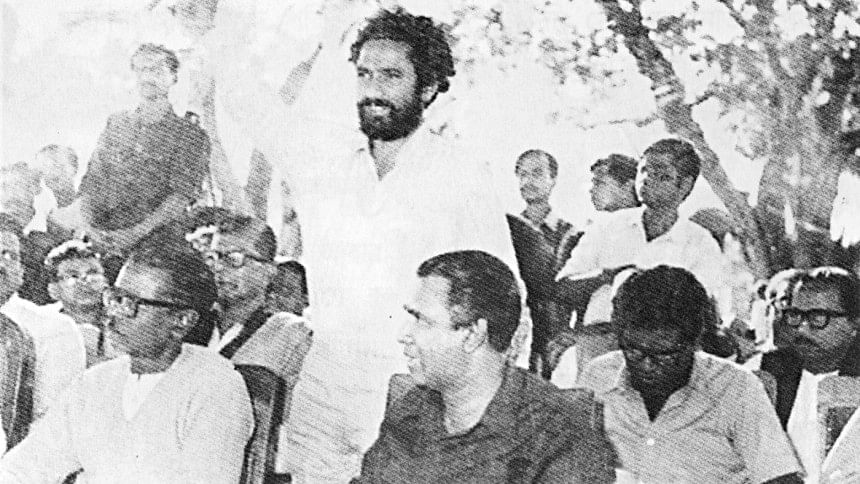

Syeda Zohra Tajuddin was a prominent leader of the Awami League and served as its president from 1980 to 1981. She was married to Tajuddin Ahmad, Prime Minister of the exiled government.

The article is translated by Upashana Salam.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments