THE GROWTH OF THE SOIL

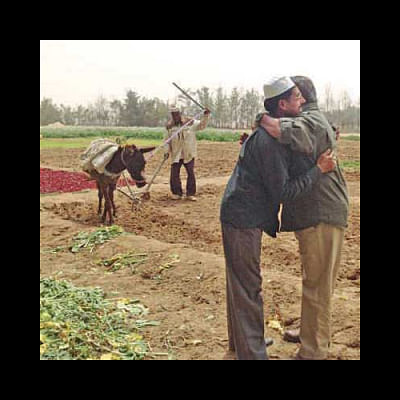

For a TV show about farmers—thin, bony, illiterate peasants, and agriculture—the mundane business of producing rice and jute, Mati O Manush might not have been a bright idea. But Shykh Seraj, award winning development activist and journalist, crafted it in such a way that it grabbed the audience by the collar and demanded attention, breaking the inertia that has always been associated with television.

“I wanted to use TV as a tool for educating the mass and giving them power,” he says. For a guy with such lofty ambitions and someone who actually delivered on them, Seraj is cool and down-to-earth. We are at his office at channel i, a privately owned popular TV channel of which he is a founding director and the head of news.

Everyone here is in a festive mood—last night the managing director of the organisation, Faridur Reza Sagor, his longtime friend, had been selected for the Ekushey Padak, one of the highest civilian awards of the country. Seraj was its youngest recipient in 1995.

The year was 1980 and more than 80 percent of the population was involved in agriculture which accounted for about 29 percent of the GDP. “A lot of people ridiculed me for launching a show about farmers,” he says, looking nostalgic.

It eventually became so popular that Bangladesh Television gave it the prime time slot—right after the Bangla news at 8 pm. “I had many barriers to break. On television, one could not speak in local dialects unless given permission from the ministry.” So here he was with a TV camera and a big microphone speaking to the rural farmers in formal Bangla and inquiring about their lives. They could not communicate with that guy. “One day I broke with tradition and started speaking in a dialect they could easily identify with,” he says in a no-nonsense tone.

He wanted to become one of them. “Back then, most farmers probably had only one piece of clothing and more often than not, it was torn. So I made a 'pilot shirt' which was usually worn by people with blue-collar jobs.”

Today the green shirt is synonymous with Mati O Manush—folks even in the remotest of villages recognise him as somebody they can talk to—somebody who, despite being a city guy, understands them. “This is what effective communication can do,” he says avidly.

A lot of people wondered why it became such a hit even among the urban viewers. “But when a farmer catches a shoal of fish and they are jumping inside the net, is it not entertaining to watch? When the camera zooms in on a vast field of dancing crops, is it not entertainment?” he looks askance.

Now that the development journalist redefined entertainment for the urban audience, he wanted to address how to get the educated unemployed involved in agriculture. “With that in mind, I concentrated on three things: beef fattening, fishery and poultry. Today the fishery industry and the poultry industry is worth 35,000 crore Taka and 30,000 crore taka respectively.”

The visionary activist had bigger plans—leaving BTV in 1996 and co-founding Impress Telefilm Ltd, the first television software production house in Bangladesh. “In 1999, we started channel i and I managed it till 2004”

During these years he did not come in front of the camera and yet Mati O Manush—literally earth and man—was still very much on his mind. He knew people wanted to watch it again. And he had been preparing by doing research on the latest technological breakthroughs to meet the new challenges.

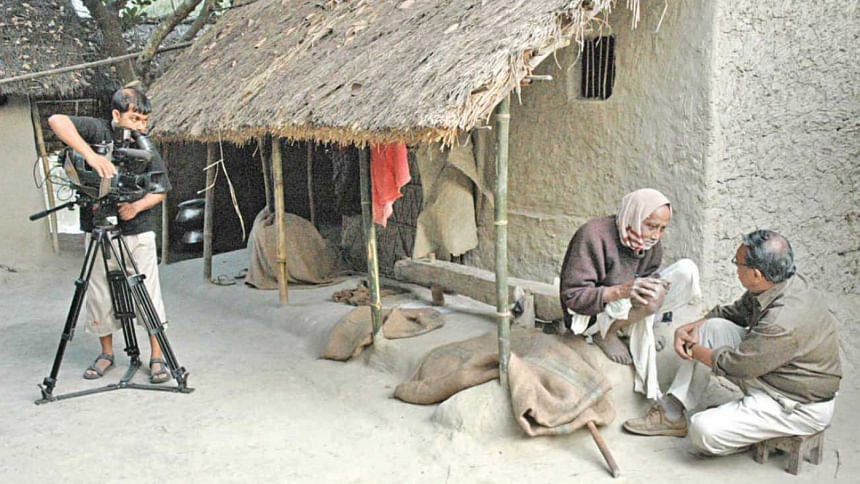

On the 21st February, Hridoye Mati O Manush took off. “This time I wanted to focus on production, marketing, policy support, best practices and new technologies. Although farmers were producing more, they were not getting the right price. I wanted to show the audience why.”

With that in mind, on an early morning on February 4, 2004, he took his crew to Belabo, Narshingdi to document how a cauliflower sold by farmers at the rate of Taka 3 each, through layers of middlemen, reached the Shantinagar bazaar in Dhaka to be sold at Taka 30. That was the first episode of Hridoye Mati O Manush aired on the 21st February, 2004. “For the first time in the mainstream media, we showed how the hard toil of the farmer is often hijacked by middlemen.”

Innovation is a word that brings to mind small, nimble startups doing clever things with cutting-edge technology. Shykh Seraj wanted to show farmers—often called the most hidebound of managers technological innovation from other countries. “I met Yang Longping, the father of Chinese hybrid rice. We went to Cần Thơ province of Vietnam where innovative irrigation system had revolutionised agriculture. We visited IRRI in the Philippines several times to learn more about the salinity-tolerant varieties.” He also took the show to countries in the Middle East, Africa and Europe to document success stories of expat Bangladeshi farmers.

Perhaps his greatest idea—he has many—is the Krishi budget, Krishioker budget which he introduced in 2005. “I did not see any mechanism within the government to assess the needs of the farmers. On the other hand, very few farmers had any idea about the national budget. The idea was to make the budget participatory.”

Farmers would gather in an open field, usually in front of a school, and share with a senior minister what they wanted to see in the national budget. They were no longer afraid to ask questions. “In 2011 in Tangail, during one such discussion a farmer said to a senior minister, 'In today's newspaper I read that MPs can buy cars that are duty free. Will the government offer similar tax breaks on agricultural equipment?”

There are, however, many challenges ahead. “Farmers need a non-partisan organisation. We have to give them more policy support. They need crop insurance. We have to switch to organic fertiliser to maintain and improve the health of the soil. Western countries are going back to family farming. We have to adopt hydroponic agriculture and better water management. We need zoning agriculture.”

At 62, Shykh Seraj still manages to get up at 4 am while he is touring. “I have travelled to more than 80 percent of the upazillas. In 2012, I went to a village in Atrai to record Krishoker Eid Ananda (a programme organising outdoor game shows for farmers). This was the first time they saw a car.”

The tireless activist wants to pass the torch to the younger generation with an initiative called Fire Chal Matir Tane. “I take English-medium students up to grade 5 on a tour to a village in Munshiganj where they plant potatoes. After three months, they go back to pick the harvest. I want them to feel what farmers for millennia have experienced.”

He also brings along university students so that they will be inspired to use their skills to help farmers. “For instance, IT students can develop an app for the farmers. The engineers can design a better plough.”

The seed Shykh Seraj planted in 1980 has now grown into a large tree. Inspired by Mati O Manush, Rahim came back home in Cox's Bazaar from the Middle East to invest taka 30 lac of his hard earned money in a farm. When he suffered heavy loss, Seraj stood by his side lending him taka 11 lakh from the Mati O Manush foundation. Selina Jahan of Norshingdi started producing compost after watching the show and founded a cooperative farm comprised mostly of women who are growing organic, diverse food crops and creating lives of courage and dignity. Last year she was given the Islamic Development Bank award as the best farmer in 52 Islamic countries. Kartik Pramanik of Chapainawabganj turned a char area into a green land by planting trees. “Shykh Seraj is like a mentor to me,” he says over phone.

The message of development Shykh Seraj has been delivering has had measurable impact. “In developing countries like Bangladesh, development communication has mostly been carried out by government agencies and international organisations,” Dr Kaberi Gayen, Professor at the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism of the University of Dhaka says. “The mainstream media's focus was generally on politics and entertainment. That's changing. Shykh Seraj has introduced participatory communication, provided people with valuable information in a joyful environment, and enabled 'diffusion of innovation'.”

The story of Hridoye Mati O Manush is epic—much like Nobel Prize winning novel Growth of the Soil by Knut Hamsun—in its magnitude, in its vast and intimate humanity. Its dominant note is the farmer's patient strength and simplicity and his tacit, stern, yet loving alliance with nature.

And Shykh Seraj looks upon his characters with a great, all-tolerant sympathy, aloof yet kindly, almost like Nature herself.

SHYKH SERAJ

Often termed as the 'Son of Soil', Shykh Seraj is a renowned media personality, agriculture development activist and a pioneer among development journalists in Bangladesh. He has been working relentlessly for three decades to promote the cause of farming and farmers in the mainstream media. Farmers' Voices in Budget, Returning to Roots, Farmers' Eid Delight, Farmers' Health Service, Grow Green, Agricultural Entrepreneurship Competition, and Agriculture News are some of his groundbreaking ideas. His revolutionary communications strategies are now studied in many countries. He is also a regular writer for online and print media and has published fifteen books.

He is the recipient of many awards among them Ekushey Padak, Ashoka Award (USA), 1992, Presidents' Award on Agriculture, 1995, FAO AH Boerma Award, 2008-2009 and House of Commons Honourary Crest, 2011.

Shykh Seraj is married with Shahana Seraj with two sons, Saqif Seraj and Ashiq Seraj. He was born in Chandpur on the 7th of September, 1954.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments