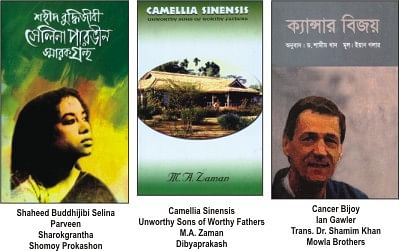

A martyr's tale, the story of tea and beating cancer

Selina Parveen remains for this country a reminder of the immense tragedy we went through in 1971 and especially in the days immediately prior to the liberation of Bangladesh. She was one of the many intellectuals picked up by the goon squads set up by the Pakistan occupation army --- Razakars, Al-Badr, Al-Shams --- in the three days preceding the surrender of 93,000 Pakistani soldiers on 16 December. Not one of those hapless Bengalis came back to tell the tale of torture, of the inhumanity that the Pakistanis and their local Bengali collaborators perpetrated on them. Some of them were never found. Selina Parveen's corpse, mutilated and in a state of gross decay, was of course found, along with those of many others. She lay, hands and feet tied, eyes bound with cloth and body pierced by what was evidently bayonet assaults, in what has come to be known as the Rayerbazar killing fields in the capital. She and her fellow dead were not murdered there; but those who took their lives made sure that the bodies were dumped there in all the depravity that brutality can call up in men of insidious intent. Those bodies were spotted and recovered on 18 December, two days after Bangladesh finally became free of Pakistan. And once the news travelled all over town that corpses littered the place, families and friends of those who had been picked up, unbeknownst to the rest of the population, made their way to the spot in expectations of finding their loved ones. The stench was overpowering. But that did not deter men like Shamsher Chowdhury (who went looking for brother Munier Chowdhury), Enayetullah Khan, Askar Ibne Sha'ikh and scores of others from scouring the area. It was Shamsher Chowdhury, as he notes in his article in this commemorative collection, who spotted the corpse of Selina Parveen among the many other corpses lying in a ditch in various postures brought about by intense torture. The rest of the story is known. Parveen's body in Rayerbazar has since become etched in the Bengali mind as a painful reminder of the pogrom the nation was subjected to in 1971. It is a recapitulation of what the collaborators of the Pakistan army, in the shape of the Jamaat-e-Islami, perpetrated in that year of unremitting agony. And the pity is that many of the leading figures involved in the killings went on not only to survive but also move up in free Bangladesh's political and social environment. The men behind the creation of the Razakar organization, the Al Badr and Al Shams have been part of the governmental process thanks to the many ironies of politics in this country. Young university students who allegedly played a prominent role in the abduction of intellectuals in December 1971 and disposing of them have entered such hallowed precincts as the civil service, with no one to check into their background. And therein lies the sadness associated with the martyrdom of Selina Parveen. She was the only woman among the large body of intellectuals abducted in those few days before the emergence of Bangladesh, obviously because of the loudness with which she had linked herself to the cause of Bengali nationalism. This anthology is a series of tributes to her and a deserving one it is too. For years after her murder, even as reflections on other dead intellectuals went on apace, discussions on Parveen's life and death remained curiously limited and muted. The reason could have been the sheer paucity of information on her, save her role in initiating and keeping alive her journal Shilalipi. It was her baby and Parveen worked for it with a passion that only one in love with her creation can. But there are too the other aspects of the story of Selina Parveen's life. She did not go beyond school where education is concerned. For a time she served as matron in a hospital. And then, as one naturally endowed with intellect, she drifted off into journalism. There was a quiet spirit in her. Tall and beautiful, she embodied Bengali womanhood as it has so often been depicted in the imagination and fiction. And part of that womanhood has always been a strong presence of purposeful thought in the personality. Not particularly happy in marriage, Parveen thought the world of her son. The son has tried repaying his debt to his mother. This anthology is proof of that devotion. Some of the leading lights of the country come together to recall a woman who went to her death even as the country she waited to be born was inexorably coming to life. She missed that great moment by three days. And she has been missed by a sad, grateful nation. Selina Parveen would be seventy eight this 31 March. YOU may not have tasted cocoa. And you may not quite be drawn to coffee. But tea is something else. It is there even if you do not need it. You imbibe it even when you know you can do without it. No conversation moves without a sip of tea, or with reference to tea. You meet people over a cup of tea. And if you have been paying attention to the English speaking of their customs, you may just have stumbled on the idea of high tea. Here, in this revealing work on tea --- so revealing that you just might be tempted to think that the book is actually a long biographical tale of the growth, life and assimilation of tea in your internal system --- M. A. Zaman opens the windows and doors wide to an understanding of what tea is all about. And he should know, for he has been deeply involved with tea and the many facets of its production in Bangladesh. Consider the way he starts off. The calorific value of a six-ounce cup of tea, he tells you, is four; and that of a similar cup of coffee is eleven. An adult Briton drinks six cups of tea a day on average. In America, conditions are slightly different since it is only of late that tea has gained popularity with Americans. Where Bangladesh is concerned, tea used to be an urban priority. But that has changed. Tea is today a significant drink in its villages. And do not forget that tea, the single commodity produced in Bangladesh under a plantation system of agriculture, happens to be a leading cash crop for the country. Think of Sylhet and you think of tea gardens, of men and women picking tea leaves in disciplined manner. And, by the way, how many among us really know that the botanical term for tea is Camellia Sinensis? That should take you back to a bit of history. As Zaman informs us, Camellia has its origins in Kamal or Camellus, a Jesuit whose preoccupation appears to have been to write about Asian plants (and that was in the 17th and early 18th centuries). And with Sinensis you have that wee feeling that tea is somehow connected with China. That is the history of tea, with of course room for other kinds of interpretation. The beauty in Zaman's work is that he makes sure that no banality comes into his narrative. He proceeds from one stage of the story to another. History buffs, those keen about the story of tea, cannot but recall the pioneers who caused tea to plant itself in these parts. Kenny Smith left Tilbury on the Thames in an old boat of about 1500 tons in November 1893 (echoes of Melville, as in Moby Dick, when a damp, drizzly November makes Ishmael take to the sea?) and made his way to the east, to India in particular. Five weeks after his departure from Tilbury, Smith reached Calcutta. That was the beginning. The rest followed. And as you flip through the pages, old names, perhaps lost to time, suddenly rise upward and remind you of the glory days when tea was taking increasingly wider swathes of territory in India. There was the Chandpore Tea Estate. And then of course there was --- and is, always --- Calcutta. It was the headquarters of the tea industry, as Zaman notes, in India and from that vantage point served as the link between the districts producing tea and distant Britain. There were other Englishmen besides Kenny Smith. Away from home, they needed all those human essentials that held up life as a normal activity. And how they were able to do that is an image you come across in descriptions of the social affairs of the early planters. It reads like fiction, or so you might suppose. It is all too real, though. All planters necessarily were members of what was known as the Surma Valley Light Horse, a cavalry brigade. There were the people needed for the nurseries given over to the production of tea. Santhals, Urias, Deshwalies and Madrasies peopled the area. Ninety nine per cent of the coolies were Hindu; and labourers were quickly organized into gangs of fifty or sixty men and women led by sirdars and sirdarnis. That is the history of the beginning of tea in this part of the world. And once you are through with it, move on into Zaman's own story. His role at Finlays and in the tea gardens keeping discipline, et al, are the centrepiece of the tale. Of course, within that telling of the tale comes, as it must, the political dimensions of the human struggle in Bangladesh as they shaped up in the late 1960s and were to reach fruition in 1971. Cancer kills. And with the background it has come steeped in, it will go on killing until science points a way out of it, someday. But that is not exactly what Ian Gawler would like to agree with, let alone pass on to others. In his motivational work, You Can Conquer Cancer, he obviously felt it was more important for individuals afflicted with the disease to remain on top of the situation. Cancer, he argued, could be subdued. And now in this admirable translation of Gawler's work into Bengali, Shamin Khan presents the entire case for a psychological resistance to cancer before readers in this country. The difficulty is that not many are willing to pore through works that are strictly of a technical nature. More tellingly, sadness that broadens out into tragedy (and cancer is tragedy, whether you like it or not) is a thought that people are forever willing to brush away from their consciousness. No matter. Gawler, himself a warrior triumphant in the battle against cancer, shows in his attitude (and Khan captures it powerfully) that the ailment need not be a source of misery through pushing people to their graves. And yet, as is argued in this translation, there is more to a tackling of cancer than plain optimism. A prime principle applied to a handling of the affliction is reflection on it. Or call it meditation. Emphasis is thus placed on the soul rather than on the more commonly talked about passive therapy. Gawler referred, in his original work, to the diagnosis proffered by Dr. Ensley Myers. And Myers did that through his acclaimed work, Relief Without Drugs. Shamim Khan holds up, in faithful measure, Gawler's stress on mental strength and psychological preparation in handling cancer or, in the extreme, coming to terms with it. Cancer need not be an agonizing, frustrating wait for the end of life; and one of the ways of making sure it is not is through bringing logic into the battle against it. Add to that the matter of food, that slight detail of what cancer patients should eat or should abjure. Take, for instance, the good that comes of eating bread prepared from wheat (atta in local parlance). And it will help immensely if vegetables are not skinned but are simply washed clean and then consumed. People who have seen their weight increase are more likely to have cancer. Gawler's simple diagnosis: eat less, eat little. And so it goes on, this relentless sprinkling of ideas.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments