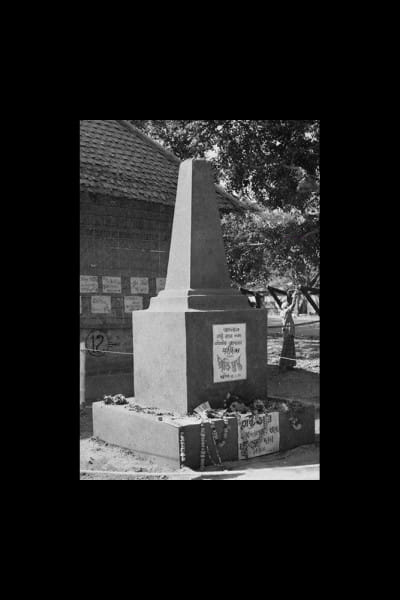

The first Shahid Minar

LATE night on February 23, 1952, a young student of Dhaka Medical College was awakened from his sleep in the middle of the night. Badrul Alam, the 24-year-old student, was sleeping after a tiring day of painting posters against the recent police firing of students on February 21 that had electrified what was then East Pakistan.

Students had flouted a government ban on assembly to demand the right of Bangla to be a state language, and police had opened fire. The death of unarmed students had stunned and shocked the state.

Palashi Barracks, the army-style barracks that served as a hostel for medical students, was in the thick of the action. After a day of protests and angry demonstrations, medical student leaders decided that they were going to commemorate the language martyrs. After elected medical student leaders made the decision, word went out to wake up Badrul Alam, who was well known for his artistic flair.

He woke up, and was told to design a memorial for the commemoration. His first draft was considered too complicated, and so he was asked to simplify it.

After the design was accepted, a remarkable thing happened. In a spontaneous outpouring of solidarity, medical students, hostel staff and other volunteers worked all night, with construction material freely donated by local contractors, to build a Shahid Smriti Stambha – a memorial to the language martyrs, which was opened to the public the following morning on February 24.

Dr. Badrul Alam, my father, was a 24-year-old youth at that time. He was posthumously awarded the Ekushey Padak in 2014 for his contribution to the Language Movement.

The first Shahid Minar tends to get obscured by the more renowned and iconic Shahid Minar that is commonly associated with the Language Movement. The second memorial was built a few years later.

I think that along with the iconic Shahid Minar, the first Shahid Minar also deserves particular appreciation and respect. The story of the first Shahid Minar reminds me of the Arab Spring movements. The building of the first Shahid Minar was a spur-of-the-moment people's response. It was a proud moment for our nation, when the fight for Bangla transcended political activism and became a popular, mass movement.

Yet until very recently, there was no decent photograph of the first Shahid Minar. How can we remember this special moment without a proper image of the structure?

Well, now we do have an excellent image, and for this the nation owes an enormous debt to Dr. Abdul Hafiz, an amateur photographer who took a photograph of the first Shahid Minar on February 24, 1952, and restored the photograph to pristine quality.

I had a chance to chat with Dr. Hafiz during his recent trip to Bangladesh. Dr. Hafiz is a retired radiologist who lives in Florida. As he reminisced to me about those fiery, emotional days of the Language Movement, it reinstated my conviction that the first Shahid Minar deserved special remembrance as a key historical moment in crystallising our passionate commitment to Bangla.

The powers-that-be certainly thought so in those days. After the first Shahid Minar was opened to the public, the overwhelming outpouring of public grief unnerved the erstwhile East Pakistan government. People from all walks of life came to pay their respects, women left their gold jewellery as donation.

Within a few days, government forces came and demolished the structure. Dr. Hafiz told me that the fact that virtually no photographs of the first Shahid Minar have survived is no accident, but the result of conscious design.

"The police and intelligence were everywhere, looking for photographs and negatives," Dr Hafiz told me. "My relatives got really worried that I might get into trouble. So I destroyed the negatives and all copies."

Fast forward to a couple of decades. Dr. Hafiz is now a radiologist practicing in Ohio. Suddenly, as he flips through an old textbook, out comes a photograph of the first Shahid Minar.

"I have absolutely no recollection of how it got there," said Dr. Hafiz. "I simply had no idea that the photograph even existed."

"It was a little damaged," Dr. Hafiz recalled. He retouched it, created a new negative and then made a digital copy of it. A copy of the photograph was subsequently displayed in his niece's home in Dhanmandi.

Meanwhile, Dr. Afzalunnessa, widow of Dr. Badrul Alam (and my mother), had been frantically searching for a proper photograph of the first Shahid Minar for years. A common acquaintance had seen Dr. Hafiz's photograph in Dhanmandi and mentioned it to her. Last year, she contacted Dr. Hafiz in Florida.

Dr. Hafiz was gracious and kind. Speaking over the phone, he said he could email it to her in a moment. Dr. Afzalunnessa doesn't use email, but her daughter Kalpana Anam did, and within days the photograph reached her.

"I just couldn't keep my tears from flowing," Dr. Afzalunnessa said. "Sixty years after it all happened, for the first time I have in my hands a photograph of Dr. Alam's work. I thank Allah for this."

For Dr. Hafiz, the Language Movement was a defining experience in his life. "After I saw the deaths, something happened to me," he said, choking up. "You know, I used to speak Urdu fluently. But after what was done to our boys, I couldn't anymore. I just couldn't."

Not only did Dr. Hafiz take the photograph, he worked until very late in the night to assist in the great labour of love of all the volunteers – the creation of the first Shahid Minar.

Dr. Hafiz has generously made this photograph available to the public domain on two conditions: He should be given photo credit, and no commercial use should be made of it.

The writer is reporter and editor of India-West weekly newspaper, based in California, U.S.A.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments