The Pathfinder

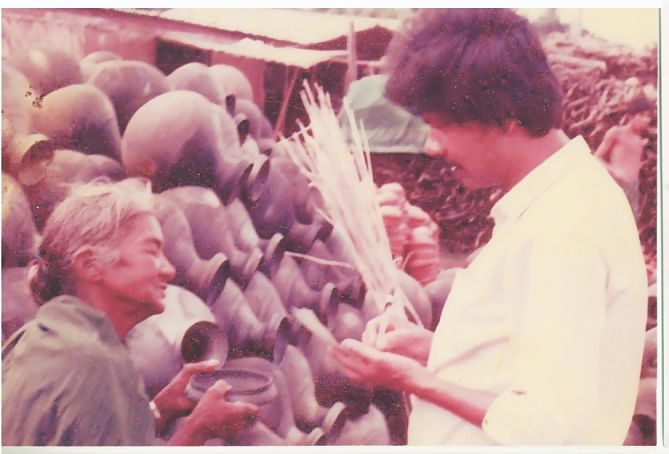

Very few journalists in the world have ever thought of using a president's chopper to send a photo film to his newspaper. But Monajatuddin did it, in 1982, sending the photo of flood-devastated Chapainawabganj. He is better known as Charon Sangbadik (bard journalist) for reporting from across the country, particularly the northern districts.

Sophisticated overseas skill training he had none. Doctorate research he had none. The daring idea of using a president's chopper is only testimony of his devotion and commitment to the call of duty.

It is because of this commitment he accepted the 24-hour deadline given by his news editor for a photo from the flood-affected area. To do that he had three options: carry the photo in person to Dhaka, which is 316km away; send it through a messenger; or via post. But journalists could hardly rely on the third option because if the package ever reached the destination, it would miss the deadline by days, even weeks. In those days, news reports used to be sent mainly by telephone.

“Will I fail?” Monajat asked himself after getting the assignment. “I will not,” he assured himself, as he later wrote in a book.

But then he gave a second thought. The road communications between Dhaka and Chapainawabganj was dead. Train would take three days to reach Dhaka.

Yet, he took up the challenge at a time when lowly-paid journalists and newspaper owners had to compromise with professional ethics. In desperate times like this, many reports were filed, often on instructions of the office, which Monajat found “brain-made.” For example, a northern district reporter of a certain newspaper once sent a report of six people dying from severe cold. Laughably, the temperature on that day was 15 degree Celsius.

“I am running the newspaper for business,” a certain owner said, when journalists pressed him over sacking of a journalist who denied to file such “brain-made” report.

It was in this socio-economic background the ambitious idea of using HM Ershad's chopper came to Monajat's mind the next morning, when he heard that the president would visit Chapainawabganj in the afternoon. Monajat placed a bet on sending the film through the journalists covering the military dictator's visit for the state-owned BSS and BTV.

But first he needs the photo. So he borrowed a motorcycle from a friend around 10 in the morning. But the bike would not get started -- the fuel tank was empty. Now he ran for having the bike refueled, but the boy at the pump was not there. But then he came, luckily for Monajat.

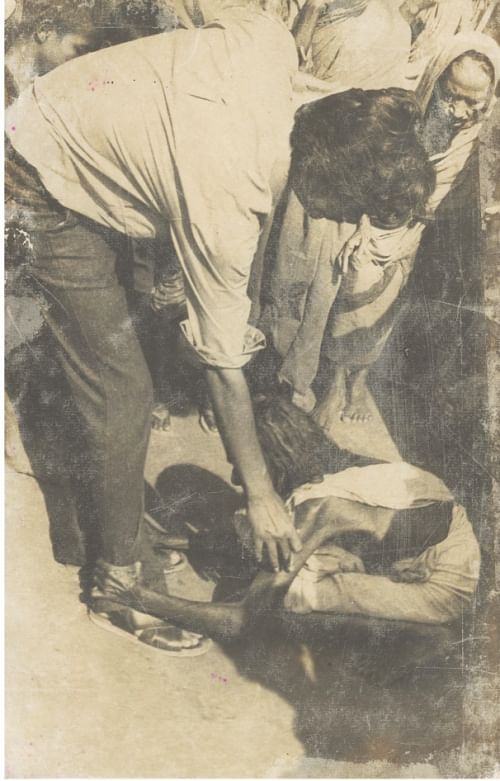

After travelling six miles on the bike, he got his photo: Some farmers swimming through a paddy field, submerged in flood water, with bundles of half-ripen sheaf.

Back with the film by 1:00pm, Monajat together with thousands of villagers was waiting for the president's arrival at Chapainawabganj stadium. But for Monajat the chopper mattered more than the president himself. The chopper landed, after three hours' waiting, with Ershad coming out first. The BTV journalist and a BSS photographer followed, but Monajat, to his shock, knew neither.

Then emerged his saviour: a BSS reporter whom he identified in his book as Robi Bhai. But between them lay an obstacle that Monajat never considered: the president's guards. His first attempt to go near Robi failed, as the president's men would not allow him. Why, Monajat did not have the “special security pass.”

Monajat employed his final card. When he made his second attempt to reach Robi, which was again foiled by a security officer, Monajat lied. He told the officer that Robi was his Dulabhai (brother-in-law) and that he must meet him at least for once.

Released from the heavy grip of the officer, Monajat started to run, crying: “Dulabhai…O Dulabhai.”

But Robi first grumbled about carrying the film. “I threw myself straight onto the feet of Robibhai…begging,” wrote Monajat, years later.

Robi did agree in the end, and the photo was published as a four-column lead in the next day's Sangbad.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments