Rediscovering nature's resplendence

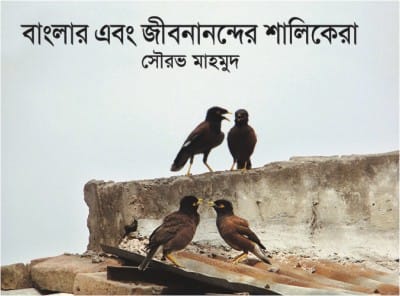

Banglar Ebong Jibananand-er Shalikera Sourav Mahmud Oitijjhya

Everyone should go back to nature every once in a while. For Sourav Mahmud, though, nature is part of the everyday pattern of life. Which is why he moves from one spot in the country to another, to rediscover all those dimensions of nature that have consistently enriched Bangladesh's environment. Mahmud is young. The brutal frankness these days is that you do not expect much of the enterprising from the young, for reasons that have to do with urbanisation, indeed that have to do with the relative ease that has come into the conduct of life through means of technology.

And yet that is not what you can hold against Mahmud. He brings back to us, as it were, all the sights and sounds which once punctuated life in the hamlets and villages of this land. Having spent much of his yet young life in a rural clime, Mahmud remains committed to a preservation of it, through noting the characteristics which have helped create the heritage of our essential Bengali culture. In this work what you therefore run into is something much more consequential than birds, in this instance the shalik that has all so often defined our links with nature. Mahmud goes into a portrayal of legacy through some of the finest manifestations of nature in Bangladesh. Banglar Ebong Jibanananand-er Shalikera has a poignancy about it that you cannot miss.

The poignant is in the writer's evocation of Jibanananda's poetry. The poet, historically noted for the sensuousness and romanticism of his verses, remains the fulcrum on which any discussion of nature moves. Sourav Mahmud thus feels free to take his cue from the poet. He goes out in search of the varied species of the shalik bird inhabiting the various regions of the country. There is a richness that he thus brings into our contemplations of nature. Note that Mahmud does not deal with the question of nature per se. He brings poetry into the discourse, reminding us that in Jibanananda as also in Tagore, the shalik has been a pivotal presence in poetry. A commingling of poetry and nature is thus achieved. And so it is that the writer proceeds into an exposition of the role the shalik has played not just in poetry but also in the collective life of the multitudes in this country.

Did you know that altogether there are a hundred and forty eight varieties of the shalik bird? Sourav Mahmud informs you that the tiniest of shaliks, just six inches in all, is Kenrick's Starling, or telshalik in Bengali parlance. And the largest is the yellow-faced mynah and the long-tailed mynah. Each is about a foot in length and weighs 225 grams each. Mahmud organises the work in review in chapters which again focus on the many varieties of the bird. The names come to us in Bengali (along with their scientific terms and English names), which is as much as a reminder of the traditions we have grown to adulthood with as it is an exploration of the nature world yet defining Bangladesh's landscape. The bhat shalik always makes it a point to arrive at the end of the rice harvest, when paddy is being dried in the sun. Mahmud takes you through a journey, stopping at a good number of points along the way. He spends a fairly good length of time educating you on the one-legged bhat shalik he spots at Curzon Hall of Dhaka University.

And, to be sure, no discussion on the bird can be complete without reference to the gaang shalik, which is shrewd enough to understand that it must make a home for itself at places where the river swallows the land in that historical happenstance called erosion. As the day pales into twilight, it is the turn of the jhoonti shalik to call out (to the heavens?) in all its charming shrillness. There is too its cousin, the dholatola shalik. The names, with all their imagery and resplendence, keep coming. The writer recalls the moment when a photo-journalist captured on his camera lens the scene of eleven go-shalik warming themselves in the winter sun in Rangpur's Darshana region. It is a sight Mahmud has come across quite often on his way to Jahangirnagar University from Dhaka. There are times, he notes, when as many as eighty or ninety of these go-shaliks are spotted together in such locations as paddy fields and chars.

Sourav Mahmud refers to the pati-kathshalik spotted by the visiting bird expert Paul Thompson at Patenga, Chittagong, in 1993. Earlier, these birds were observed on St. Martin's Island in the early 1980s by Dr. Reza Khan, a well-known nature observer of the country. The writer would have us know that this variety of shalik is generally to be seen in regions with a cold climate, notably Europe and west Asia. The pati-kathshalik is a most colourful bird, with different colours giving it an appearance like no other. And then there are those shalik that are not to be seen on a regular basis. Think here of the chitipakh telshalik. The records show that the bird was seen in Sylhet in the nineteenth century. In more recent times, this variety of shalik was observed in Dhaka in 1974 and then again in Sylhet in 2005.

The work takes you away from the world of mundane realities and into a poetic landscape where nature's wonders are predominant. Mahmud takes you back to Jibanananda's poetry, the better to instil the point in you that the shalik and by extension the natural world have been integral units of the Bengali literary consciousness.

Banglar Ebong Jibananand-er Shalikera is a necessary lesson in how not to let modernity push the natural environment to the fringes. It is, additionally, a call for a return to some of the basics, indeed values, which have shaped sensibilities in our part of the world. Long ago, in our adolescence, we climbed trees in the rustic clime to observe birds' eggs in their well-ordered nests. Having observed, and felt, the eggs, we replaced them in the nests. Sourav Mahmud has passed through similar experience.

The generations thus connect. And all of us must perforce connect with the world of birds, for birds remain a potent and profound symbol of Creation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments