"Genocide is very often a response to an extreme political threat."

The Daily Star (TDS): Please tell us something about the origins of genocide.

Dr. Andrea Bartoli (AB): Genocide is a very old phenomenon. Addressing differences through violence is not a norm but certainly happens often enough. Genocidal violence can be traced back to the very old past. We have historical cases of cities and populations that were wiped out; there are even pre-historical cases of villages that were raided and destroyed. We know that humans have this capacity for destruction. What is specific about genocide, though, is that it is intentional and against a certain group --- a national, cultural and/or religious group.

TDS: What is the significance of Bangladesh in this respect?

AB: The case of Bangladesh is a very important one. It happened after the approval in 1948 of the International Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes of Genocide. The importance of this convention is that it gave a name to this phenomenon. So you have something that happened many times but there was no name for it. It was not just the violence of war or an oppressive regime. This was a specific type of violence -- intentional attacks against human groups. It is particularly important because when it happened in 1971, the world had a concept of what was happening.

It was a period in which the convention existed formally but there was no real desire on the part of anybody to really act on those words. I describe this as a period of wilful neglect. People knew that the convention existed but they were ignoring the fact. They pretended that the convention never existed. This was particularly true of the Pakistani military that attacked the Bengali population. It was not the first time that an entire population was under oppression by a powerful force. What was different in this case, however, was the military attack against civilian populations. It was unleashed with extreme precision and great effectiveness. The operation was not carried out as part of the civil war; it was actually a response to the electoral results that changed the course of Pakistan forever.

The Pakistani military decided to wage war against Bengali civilians and authorities, and found a popular response against their decision. They lost the war and the capacity to pretend that nothing had happened. The millions of refugees, the thousands of women that were raped, and the hundreds of thousands of families that were affected by the violence recognised the brutality of those nine months.

In many ways, we are still grappling with those memories.

TDS: What do you have to say about the legacy of the genocide in 1971?

AB: There is a connection between the legacy of 1971 and what we are experiencing now. The fundamental question of genocide in 1971 is still alive today because there were people who believed that violence and war could be advantageous for them. Many of these people even believed that it was their duty to commit genocide, be violent and engage in war.

They justified the war on the grounds of state interest and religion. They claimed that the Bengalis were not Muslim enough, and needed to be converted into true Muslims.

Nobody is violent just for the sake of being violent. Violence in this context is always a means to an end. The problem we are facing today is that people still believe that they can use violence, genocide, and war to obtain political results.

TDS: Why do you think people resort to extremist ideologies?

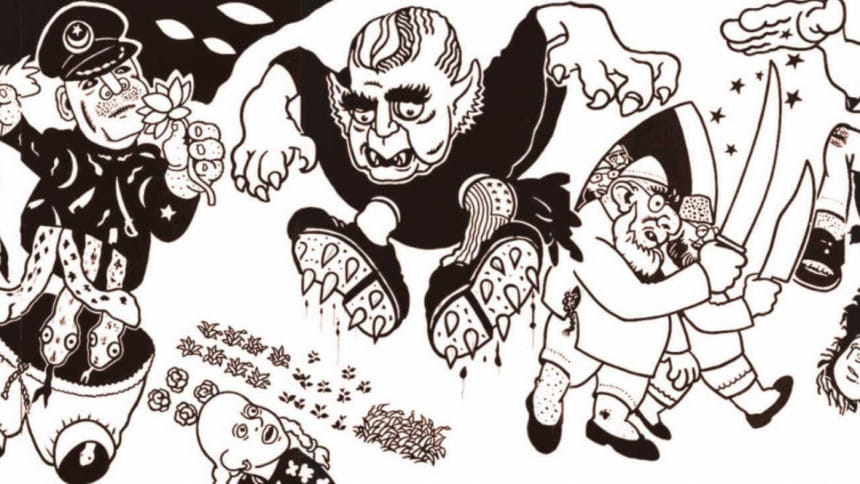

AB: People become convinced that violence is the best solution for them, or in some cases it is their only solution. When they don't make much progress, they start to believe that the use of violence is not only justified but also a duty. To those who commit genocide, the sense of threat and duty is very important. They construct the victims as danger. They view the victim along these lines: 'You are a danger to me. I need to kill you, eliminate you because otherwise I will not exist as I am now or as I would like to exist.' Genocide is very often a response to an extreme political threat.

TDS: How can justice be implemented in this regard?

AB: Humans are a very poor example of the values of justice. True justice comes in a religious sense and spiritual sense. The states that are now calling for prevention of genocide are the same ones that were doing nothing when Bangladeshis were being murdered.

Taking Avijit's case… Even if the perpetrators of Avijit's killing are not caught or brought to justice, greater justice would be when the majority of the population of Bangladesh says, 'Killing is wrong. Killing somebody for saying something is wrong. Killing in the name of Islam is wrong.'

Justice is not only in the hands of specialists, lawyers, judges and prosecutors. Justice is first and foremost a relation between people. Every time we allow the victim to speak, give the victim a voice, and point out when something is wrong or immoral, it makes justice stronger.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments