A legacy of excellence in public service

The passed away quietly and unheralded. Probably, that was how he would have preferred to go, after having courageously and gracefully battled a deadly cancer of the kidney for six years. He was the epitome of everything that was good in our traditional public service. Civil bureaucracy from time to time, has been derided as a colonial legacy. Nevertheless, whether we like it or not, many of our great institutions have been in fact, inherited from the British regime. University of Dhaka, the zilla schools, the judiciary, the legal system, local government, the armed forces, the railways and finally, our much vaunted Westminster model of parliamentary government itself that we have been desperately trying to turn into a meaningful reality.

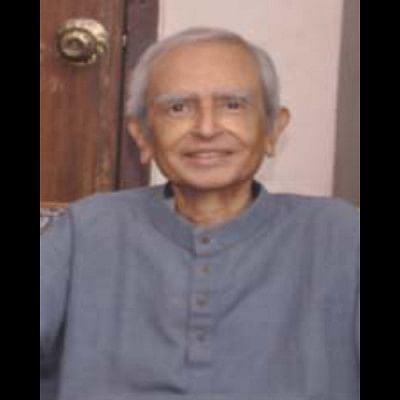

Faizur Razzaq, belonged to a dynamic generation of the '60s, the new emerging middle class in East Bengal, striving hard to excel academically. This generation also took great pride in a burgeoning national identity, trying hard to promote democratic values and demonstrating an earnest commitment to public service for development. He was recruited into the top echelon of the government through a very rigorous selection process of the Central Public Service Commission. He obtained a Master's degree from Harvard University in economic development. He was a seasoned, well-tested field administrator as well as the chief executive of corporate entities within the government and outside. He had served with distinction as secretary to the Ministry of Energy, managing director of Bangladesh Biman, director general of Bangladesh Television, Secretary of the Election Commission and numerous other government agencies.

His last assignment was that of the managing director of Grameen Fund, a social venture fund which was set up at the instance of Professor Yunus of Grameen Bank.

He also represented Bangladesh in the Asian Development Bank, in his capacity as an alternate executive director, late in the '90s. He had served ADB with great distinction and demonstrated his professional excellence. So much so that the then President of ADB, Tadao Chino, very keenly wanted Razzaq to join his management team as a vice president -- he would have been the first Bangladeshi to occupy such a position -- back in 2001. In fact, the President of ADB himself came all the way to Bangladesh, only to lobby with the finance minister and the prime minister, so that the government would agree to ADB's proposal. Unfortunately for Bangladesh, the government did not agree because of internal bureaucratic wranglings. As a result, we lost an opportunity of having a Bangladeshi vice president capable of influencing strategic policy making in the most important financial institution of the region .

He would be a role model for young civil servants today. Like a true public servant, he performed his duties with great humility. He would shun publicity like the plague. He was ever polite, most polished and erudite in his manners. He was not only highly accomplished academically, but also professionally trained in policy making that required application of interdisciplinary skills, with an amazing capacity to interact with different categories of people, at home as well as abroad. He had a way of making friends with strangers, winning an adversary over to his side. Even in the midst of a heated debate, he would break into a heart warming smile. I had never seen him lose his temper or speak to any one out of anger.

Throughout his professional career as a civil servant he remained passionate about attaining perfection. Most importantly, he demonstrated ethical values of the highest order that are lacking in public service in today's turbulent times. While corruption became the norm, he remained steadfast in terms of his personal integrity. He was truly a non-partisan, a pure professional, in the midst of rampant partisan politics. He remained humble, yet fiercely dedicated, when civil servants these days tend to be arrogant and indifferent to their tasks.

I have often asked myself this question: "How does a civil servant acquire excellence?" Good academic qualifications, practical work experience, personal integrity, dedication to one's work, firmness at times of crises, etc are all necessary, but they are not sufficient for attaining excellence. Dr. G.C. Dev, who was not only an eminent teacher, but also delved deeply into basic moral issues of our society, summed up the paradox of modern professionalism very neatly. Simply put, it means that we do not practice what we preach in our respective occupations, whether as an engineer, or an administrator or a politician. He writes in his book titled Aspirations of the Common Man: "We must remember that this badly needed reform cannot be effected by mere profession. It has to be done by practice, hard practice, I should say. The great gap between modern man's profession and practice is the root cause of his almost endless troubles and, for the sake of a better world and a better existence, we must put an effective brake on this disparity."

In performing his tasks Faizur Razzaq adhered to the highest ethical standards, a pre-requisite in current public administration. I would illustrate this with an experience which I shared with him during the tail end of his career. I was astonished to learn that every September, he would visit the office of the assistant commissioner of income tax, a junior officer under the National Board of Revenue, to personally submit his tax papers. As a senior government officer there was no need for him to physically hand over the tax returns; it would be normally expected that his private secretary or personal assistant would do the needful. But Razzaq felt that he was publicly accountable and it was his moral obligation to submit the return personally to the concerned tax officer. In spite of being a secretary to the ministry, he took great pains to explain to a junior official the details of his tax assessment. Even during his terminal illness he was extremely anxious to discharge this particular responsibility. On several occasions he had asked me to submit applications on his behalf to the concerned officer, explaining the nature of his illness, regretting his inability to file the return personally within the prescribed dateline. Paying duly assessed taxes regularly and disclosing to the concerned officer, all information relating to his income and assets owned by him, was part of his elan of public service.

Now that we have lost Faizur Razzaq for ever, I realise what a precious legacy of public service he has left behind for all of us. It is a legacy of professional excellence, combined with personal integrity of the highest order. Above all, he stands out as a great human being, full of empathy for people whom he had served with all humility, without any fear or favour. In these difficult times, when partisan politics reigns supreme, can we aspire to build a public service based on these universally recognised, time honoured values? These values, in the ultimate analysis, represent the bedrock on which good governance is founded. Time seems to be appropriate that we initiate a debate in these matters involving all the concerned stakeholders.

The writer is retired Civil Servant.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments