No place to belong

THAI authorities detained 76 migrants including six suspected Rohingyas in Thailand's southern Nakhon Si Thammarat province on Monday. The group is said to have been heading to Malaysia in search of work. In January, a group of 98 suspected Rohingyas were also found in pickup trucks in southern Thailand.

In a controversial move, Myanmar's government revoked temporary voting rights of people holding identification cards seeking citizenship after President Thein Sein declared on February 11 that said ID cards will expire on March 31, 2015. Presidential office director Maj. Zaw Htay said that the government's decision "automatically annuls the right" of temporary residents holding "white papers" to vote in the upcoming constitutional referendum. White card holders are now required to hand over their cards by May 31. The white papers were introduced in 2010 by the former military junta to allow non-citizens such as the Rohingya and other minorities to vote in a general election.

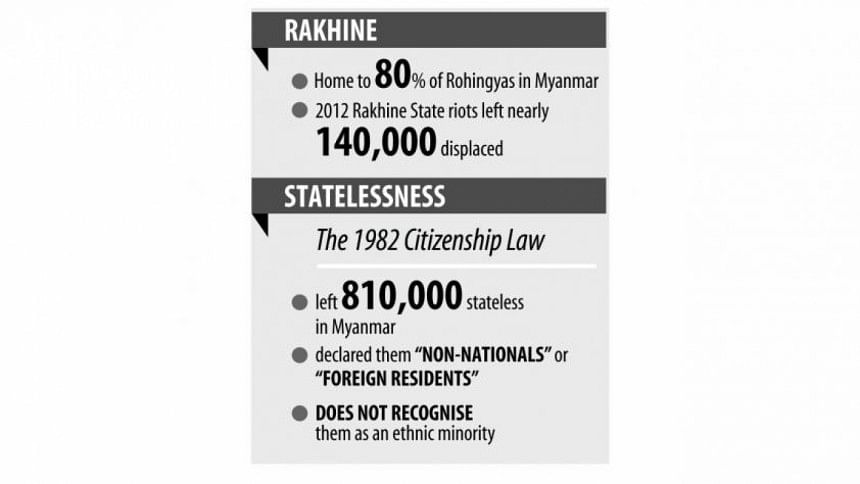

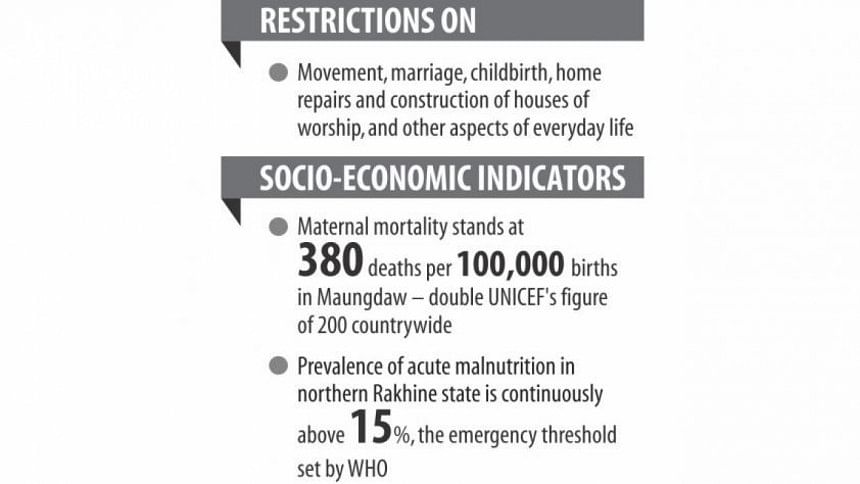

The Rohingya, one of the most persecuted minorities in the world, are internationally recognised as de jure stateless. The ethnic Muslim minority is denied citizenship under the country's military-drafted 1982 Citizenship Law. Sectarian violence and statelessness have resulted in structural impediments to progress for the Rohingya because of a lack of access to basic necessities, and restrictions on their freedom of movement and religion stemming from long-standing discrimination and repression of the minority.

ROHINGYA FACTBOX

Conflicting narratives

Moshe Yegar, heralded as an authority on the history of Muslims in Myanmar and author of "The Muslims in Burma", traces the origins of the Muslims of Arakan (now known as Rakhine) back to the ninth century when Muslim seamen first reached lower Burma and Arakan. According to Yegar, events such as the Mogul invasion, Burmese invasion and WWII which saw large-scale transnational movements of Muslim populations, played an important role in shaping the demography and politics of future Arakan. Today, the Arakanese Muslims call themselves Rohingya.

The other narrative, mainly driven by Buddhist nationalism, within Myanmar is that modern day Rohingyas are descendants of colonial-era (1820s) immigrants from Bangladesh. This dominant narrative has been challenged by many sympathetic to the Rohingya cause. One of the claims that refute this narrative is Francis Buchanan's (a surgeon with the British East India Company) firsthand account of travelling to Myanmar in 1799 and meeting with native Muslims who called themselves "Rooinga," indicating the presence of self-identified Rohingyas years before British rule.

Politicisation of identity, race, religion

For years, people of Arakan were known as Rakhines until some started being referred to as the Rohingya because of linguistic differences. Soon, the politicisation and dichotomy of the two identities ("Rakhines" for the Arakanese Buddhists and "Rohingyas" for the Arakanese Muslims), the foundations of which were laid in the colonial-era, led to the continued subjugation and statelessness of Rohingyas.

Changes in the demographic composition in the 1960s and 70s in Arakan due to large numbers of Buddhists migrating eastward provided the Myanmar government with the opportunity to use divisive tactics of race and religion to consolidate support. The government blamed the demographic transition of the declining number of Buddhists on illegal migrations from neighbouring Bangladesh. To make matters worse, in 1976, an alleged coup involving both Arakanese Buddhists and Muslims failed to come to fruition. Fearing the increased likelihood of an armed rebellion by Rohingyas residing in villages, the government forced the migration of more than 150,000 Rohingyas into Bangladesh by mid-1978.

The democratic movement that united the Arakanese proved to be a threat to the military regime following the end of Ne Win's rule in 1988. The age-old tactic of race and religion came in handy once again as the regime successfully drove a wedge between the relations of Buddhists and Muslims. The military, backed by China, cultivated an artificial racial situation in order to maintain a larger population of racially Mongoloid Buddhists in hopes of consolidating power with its "populist policies."

Stateless to refugee

The antagonism of the local populations in the border regions towards Rohingyas can be attributed to multiple reasons including the criminalisation of the ethnic group by the police on both sides of the border. The transition of their status from that of stateless to refugee has had severe consequences, and fuelled the militarisation of pro-Rohingya political fronts making the situation even more volatile.

Whether or not the Myanmarese government is exploiting the conflict-ridden region to attract developmental funds and foreign investment by driving Rohingyas out of their homes and forcing them into physical labour has come into question. For Rohingyas, multinational companies' investments in the region and the resulting economic relationship between the Myanmar government and the international community means their plight being "doubly marginalised" - nationally and internationally.

Ignored for too long

The prevailing debates about the Rohingyas' origins seem to serve as a convenient pretext that does nothing but detract from the current, much larger issues arising from their continued persecution. The failure of Myanmar's government to recognise them as citizens has prolonged their stateless status and deteriorated their condition. The 1982 Citizenship Law makes it nearly impossible for the Rohingya to ever attain citizenship; this draconian law represents one of many forms of institutional oppression and systematic denial of the minority's universal and inalienable rights.

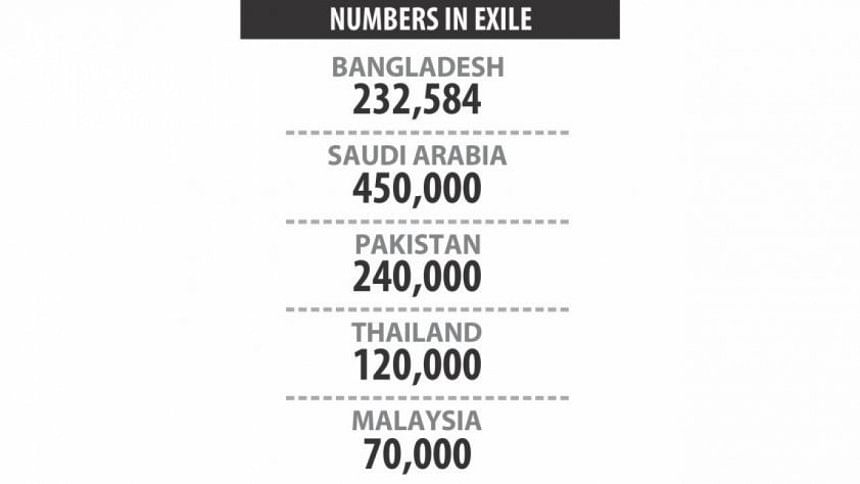

The Rohingyas' abuse, humiliation and state-sanctioned paralysis have become normalised. Even the use of the word "Rohingya" in Myanmar is controversial as it invokes deep fear among Buddhists that the minority may seize their homeland. The deplorable humanitarian conditions and undocumented status of Rohingyas in Bangladesh, Malaysia and Thailand among other places have been reduced to mere headlines; pro-active approaches and viable solutions for this humanitarian crisis are severely lacking. Despite there being an agreement among six South Asian countries on a "regional solution," visible leadership is yet to be seen.

The Rohingyas, although portrayed as highly disempowered (and they are on many levels), must be recognised for their resilience and strength in the face of such cruel adversity. As refugees, their skills of adaptation and determination to survive are remarkable. While the international community ignores their worsening plight, the Rohingyas continue to fight to prove their existence everyday.

The writer is a journalist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments