We lament your absence

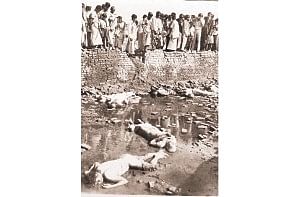

Even from a definitional standpoint, the killing of the intellectuals in the final moments of the war can certainly be termed as genocide. It is genocide because it could not have been invented overnight and must have been well thought-out and rationalised at the highest levels of the Pakistani government and military machinery. There is documentary evidence from the notes found on Rao Farman Ali’s desk that this was a planned and co-ordinated operation. We shall try to reason-out the rationale that must have driven the Pakistanis to take this route. First is the deep-set belief in the Pakistani mind that the Bengali brand of Islam was a polluted one, in which popular folklore and the baul philosophy, etched in the colours of the sanatan origins of the Bengali people had made deep inroads into the desert-dry, austere brand of Islam, shorn of adornments of any kind –which they were familiar with, ostensibly from their proximity to the Arab lands. Then there was the fear in the Punjabi folk traditions about Bengali witchcraft, which they did not understand, so in their trigger-happy state of mind in 1971, the easiest way to deal with it was to spend a bullet. The third factor — a belief which even the ordinary Pakistani shared — that their land of the ‘pure’ was poisoned by the presence of one crore Hindus still left in the country who would have to be replaced with true Islamic blood brought from Bihar, (of all the places!) as one Pakistani army officer, who I had given a ride on one of my trips to Tongi in April, had confided in me. Then there was an inferiority complex which lurked in the mind of the Pakistani elite that the superiority which Bengali literature, painting and music was endowed with (despite its creators being largely of “Hindu” origin) and the sheer weight of modernity which was carried in them, would one day overtake what West Pakistan had to offer. They were mortally afraid that this could have a lasting effect in shaping the minds of not only the Bengalis but eventually of the Pakistani elite as well. It therefore is no surprise that so many of the December victims were men who had something to do with creative work.

Bengalis were lucky that the Pakistani military establishment crumbled like a house of cards not only in East Pakistan but also in the Sind and Azad Kashmir theatres within a few days after December 3. Not only was Dhaka cut-off from the rest of East Pakistan but the amount of exchanges through friendly countries could hardly sustain a meaningful communication between Yahya Khan and Niazi. The battle-weary and bewildered Pakistan army was gasping for breath and had other more desperate issues to deal with for their survival than carry through the master plan they had carved out for crippling the Bengali superiority in the intellectual world. Farman Ali did the best he could under the circumstances, using his foot-soldiers, the Al-Badr Bahini.

In Munier Chowdhury, Shahidullah Kaiser and Moffazzal Haidar Chowdhury we lost those people who could have given the intellectual world of this country the kind of leadership that would guide this nation for generations. Brilliance they all had, but what distinguished them from the others is that had they lived, they would have been able to combine creative skills with political insight and give artistic and creative work a dimension which would be hard to quantify today. Along with the other men of the cultural world who perished with them, they had the wisdom to comprehend how creative work may be combined with the energy and vigour of a new nation and steer it along so that the legacy nurtured so far mainly by people from West Bengal would be reinforced with the energy of people bubbling with the enthusiasm of having created a new nation. Bengali creativity could have been catapulted to heights which the Indian cultural world had not witnessed before. In losing them to the daggers of the Al-Badr butchers, the nation lost out in creative genius.

The Bengali society suffered another great loss through the killing of the intellectuals, a loss which on a long-term basis has affected us profoundly. That criminal act was not done in the dark nights of December alone, but carried out on every desolate night of the nine months. Thus the society was cruelly purged of those who were the bulwark of the ethical and moral value system that the Bengali society carried. The moral fabric, woven from the yarn of intrinsic values that our societies had held for generations and the yarn spun by the light that western education had imbued in us, is now in shreds as a result. The entire society today suffers from a loss of ethical values; it has become intolerant of the underprivileged — be it of the religious, financial or gender kind; and it nurtures fundamentalist tendencies. We suffer the vacuum that they left in our everyday life. And let us not blame the politicians alone because values have been eroded from the lives of academicians, army and civilian bureaucrats, businessmen and even young students, many of whom have become millionaires before they even cross the gates of their Universities. The intellectuals whose absence we are lamenting today would have provided those moral values.

The writer is a Social Activist and Trustee, Liberation War Museaum.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments