Gunter Grass in Dhaka

One day in November 1986, Dr Shamim Khan – friend, colleague, and at that time an assistant professor of International Relations at the University of Dhaka – asked me if I could do him a favour and collect Gunter Grass from the Ford Foundation Guest House and take him to our University. I jumped at the opportunity, for when would I ever have the occasion to chauffeur someone of the stature of Grass again? I had read Grass's masterpiece The Tin Drum in the early seventies and had seen the brilliant film version of the book directed by Volker Schlondorff in Vancouver in 1981. I had also read a few of his poems in translation. The very idea of spending a few hours with the great writer was immensely exciting. I was also thrilled to get an invitation to a reading by Grass on the 5th of December at the residence of the Director of the Goethe-Institute, followed by a reception. All in all, a most unusual encounter with a giant of contemporary literature seemed to await me.

On December 7, Shamim and I went to the Ford Foundation Guest House in Dhanmondi. Gunter and Ute Grass were ready and so we were soon on our way. I can't remember what we talked about on the road but recall that the Grasses were polite and not unfriendly. Although his mustache gave him a gruff look, it was immediately clear to me that he was anything but unfriendly. He also appeared to be genuinely interested in learning about our world. I remember too that he was very curious about what was going on then in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and asked us a number of questions about the situation there. He wanted to find out too about Dhaka's Geneva Camp and the plight of Biharis. It was obvious that he was not going to play the tourist in his visit and was more interested in social-political issues. But how could we expect anything different from the author of The Tin Drum?

From the few hours that I saw the public persona of Gunter Grass, I remember most the frank, even blunt way in which he fielded questions. For instance, a senior colleague – a creative writer of note – asked unaccountably gleefully, "How did you like our slums in your visit?"

Grass shot back at him with obvious irritation and disgust, "You ask too many stupid questions!"

Earlier on, someone asked Grass: "What do you think about your not getting the Nobel Prize?"

The question irritated the writer visibly, and it was clear that the same question had dogged him throughout his stay in the sub-continent that year, for he parried it by saying, "Why are you Bengalis so obsessed with the Nobel?"

But in the few exchanges Shamim and I had with Grass and his wife, we found them to be invariably pleasant. I was, of course, a bit awed by him but had the temerity to ask him to autograph my copy of Gunter Grass: Selected Poems. He was entirely gracious in his response. I treasure this copy, made so distinctive by his looping, artistic signature. When we parted outside the Dean of Art's office, he gave me a dozen or so copies of an Amnesty International report on atrocities committed by the Army, requesting me to distribute them to people who were concerned about the situation in the Hill Tracts. Because I had always believed that our Army should disengage itself from the Hill Tracts, I was only too glad to help Grass in distributing the report. And it was pleasing to think that Grass had found in me someone he could enlist in the worldwide campaign to draw attention to the injustice being committed in the name of settlement and pacification in the region.

A thoughtful account of the German writer's visit to Bangladesh in Dhaka is to be found in my friend Kaiser Haq's essay, "Gunter Grass in Dhaka". Although Kaiser was away in America at that time, he was curious enough to gather our impressions and those of a few others and to read the newspaper stories of the visit to write a probing piece on Grass in Bangladesh. In his essay he points out how the Ershad-run broadcasting system had no time for Grass's abrasive views on our treatment of the people of the Hill Tracts, and how even a "progressive" Bangladeshi writer scorned Grass's advice that the miserable condition of Dhaka's Geneva Camp merited the attention of our intellectuals. Kaiser stresses how Grass refused throughout his stay to say things merely to please his audience and how the uncomprehending and even indignant Bangladeshi reaction to the novelist's outspokenness "crackled with ressentiment, the rancor of the weak towards an external world seen as hostile and evil". I would add that someone like Grass, given to plain-speaking, and committed to the belief that the writer must be incisive in combating injustice, was an anomaly in our part of the world where it is important to be "nice" and to not seek the role of a gadfly.

It is good to have Kaiser's essay (originally published in London Magazine) reproduced in part in the admirable collection of articles, interviews, and comments, assembled by the German writer, Martin Kampchen in My Broken Love: Gunter Grass in India & Bangladesh (New Delhi: Viking 2001). Kampchen, it can be pointed out, has devoted himself to promoting cultural relations between Germany and the Bengali-speaking world, as is evident in his two very useful collections, Rabindranath Tagore and Germany: A Documentation (Calcutta: Max Mueller Bhavan, 1991) and Rabindranath Tagore in Germany: Four Responses to a Cultural Icon (Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1999). Certainly, his compilation of articles on Grass's visit to the sub-continent will prove as useful as his earlier work in furthering German-Bengali relationships and will be indispensable for anyone wanting to understand Grass and his fascination with our part of the world.

The focus of Kampchen's book is, inevitably, Grass's several visits to India, especially his five-month stay in Kolkata in 1986. Dhaka was really a sideshow for him, but My Broken Love also includes Rashid Haider's enjoyable account of the Grasses visit to his home in Dhaka and Nasir Ali Mamun's vivid photographs of the German novelist's Dhaka visit. Both Haider's narration of the visit to the Haider family and Mamun's photographs are enjoyable because of the way they reveal the lighter and more private side of Grass. The reason Grass went to the Haider house in Dhaka had to do with Grass's acquaintance with Daud Haider, the ostracized Bangladeshi poet who had fled Dhaka in the early eighties because of a poem he had written that had offended many people's religious sensibility. Daud Haider had become Grass's guide in Kolkata and Grass was eventually able to find a way of taking the exiled Bangladeshi writer to Germany. Not surprisingly, then, Grass had wanted to meet the Haider family in his Dhaka trip.

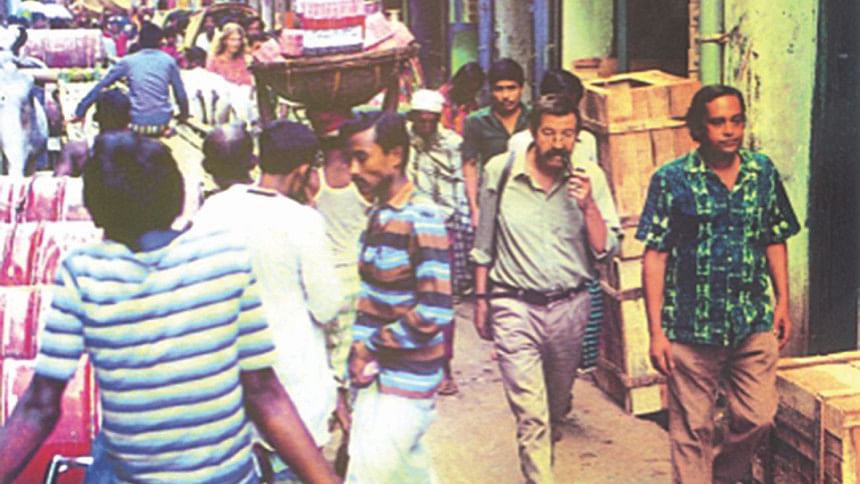

Rashid Haider's engaging reportage of Grass's visit to his house was originally published in Prothom Alo, and is ably translated for Kampuchen's book by Lubna Marium. According to Rashid Haider, Grass was intent on seeing Haider's fourteen brothers and sisters, five of whom were writers, and had thus sought the trip. The mischievous side of Grass comes out in Haider's telling of the visit, as when the German writer comments that "the wives of geniuses were always taller than their spouses," and that his wife Ute was, in any case, "greater than he was" since he was totally under her control! Haider points out that in the time he spent in their house, Grass displayed "not a trace of arrogance, nor any intellectual airs", and his "humanity, a concern for mankind, an unfeigned empathy for the downtrodden" was everywhere evident in the three hours that he spent with the Haider family. The photographs by Nasir Ali Mamun reprinted in Kampuchen book—of Grass and Utte visiting a pottery, appreciating Zainul Abedin's famine sketches, visiting a classroom and walking on a street in Dhaka, and of Grass and some slum children further corroborate Rashid Haider's testimony.

My Broken Love is compelling reading because it shows how Grass's visit to Indian and Bangladesh grew out of his love for humanity and his belief that it is important to confront misery and hunger everywhere in order to overcome it. The title of the volume is from an interview Grass had given during his second Kolkata visit when he had noted that he had come back to the city for another time because "you only come back if you love something". Although Grass obviously enjoyed many aspects of the sub-continent, just as obviously he was hurt by much of what he saw of the suffering of ordinary people in the trips he made to the region. As Kaiser points out in his piece, Grass had titled the book he had written of this extended stay in the city and India Show Your Tongue to emphasize "the subcontinental habit of sticking out the organ and lightly biting on it to convey anything from surprise to disgust to horror". But it is the horror of someone genuinely moved by what he sees and not the disgust of a detached and arrogant Naipaul that Grass exhibited throughout his stay and his comments afterwards. As Grass observed in the Nobel Lecture that he delivered in Stockholm in 1999, "Anything the human mind comes up with finds astonishing applications. Only hunger seems to resist...It takes political will paired with scientific know-how to root out misery of such magnitude, and no one seems resolved to undertake it". This speech is reproduced in My Broken Love. Kampuchen also tells us in his helpful Introduction that Grass has continued his effort to spotlight the poverty and alleviate such a situation not only by writing about it but also by contributing substantially to projects such as schools for slum children in Kolkata and Dhaka after his return to Germany.

While I have stressed the parts of My Broken Love where Kampuchen features essays on Grass in Bangladesh, there are many articles in the book on Gunter Grass in Kolkata that will be of interest to readers here. One should thus read Shankarlal Bhattacharjee's "Impressions of Gunter Grass in 1975 and 1986" for its glimpse of the German writer among Kolkata's literati and Daud Haider's "Guiding Grass through Calcutta" where the exiled Bangladeshi poet reveals himself as an irresponsible and overenthusiastic cicerone. Subhronjan's Dasgupta's "Two Afternoons with Gunter Grass" is interesting for its detailed account of the Grass's unusual daily schedule in Kolkata. There are two intimate accounts of Gunter and Ute Grass in the painter Shuvaprassanna Bhattarchaya's "Gunter Grass, the Tin Drum Player of Calcutta" and Tripty Ghatak's "Elder brother Gunter Grass: Simple Memories of a Sweet Relationship" which testify to his capacity for friendship and his affectionate nature. Kampuchen has also included at least three interviews that reveal to us Grass's reasons for visiting Kolkata, his views about the west, about east-west relationships, and the future of humanity. The impression that one gets always from the answers Grass gives to his interviewers is that of a sensitive and original thinker, passionately committed to arousing our consciousness about injustice and thinking through things. When asked, for example, in an interview about the partition of Germany, Grass chooses to reply to the question by observing that as in East and West Germany, Bangladesh and West Bengal had many things in common: "There are different political systems, differently organized states, differently dressed soldiers, but the social problems are linked together: the growing unrest between a small group of middle-class and upper-middle class people and the large group of underdogs".

Such forthright comments and strong generalizations of course can't please everyone. Kampuchen's My Broken Love contains disapproving views of Gunter Grass too. The filmmaker Mrinal Sen thus indicates in a letter to Kampuchen that Grass was improvident in the steps he took in settling down in Kolkata and was bound to contribute, albeit unwillingly, to the negative impression westerners have of Kolkata. The Indo-Anglian writer P. Lal declares in an interview that Grass was predisposed to disliking certain things and was somewhat brash in some of his comments. And S. V. Raman's doubts about Grass is amply reflected in the title of his piece: "He Came, He Saw—But did he Conquer?"

Nevertheless, such negative estimates of Grass only make Martin Kampuchen's My Broken Love: Gunter Grass in India & Bangladesh more readable and valuable. It also makes Gunter Grass's interest in our part of the world more fascinating. But the last impression left by a reading of the book is how admirable Gunter Grass the man is even if he can be abrasive and opinionated at times. Kampuchen book is thus a good introduction to a no-nonsense but passionate man, of a controversialist, yes, but one fully committed to humanity and against hypocrisy of any kind, and of a creative artist seeking for new ways not only of representing humanity in his works but of also alleviating its sufferings through his actions.

Fakrul Alam is a Bangladeshi academic, writer, and translator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments