Consuming Unspeakable Tragedies

LIGHTS. Camera. Action. The camera zooms in on a traumatised, grieving mother. A microphone pokes at the woman's face, and an ever-zealous reporter (outside of the frame), interrupts her wailing to decipher her onubhuti (feelings): "how do you feel now that your son's body has been recovered?"

The camera remains unmoving and voyeuristically on the wailing mother's face as she struggles to render intelligible her emotions for mass public consumption. How does she feel, indeed, I wonder, to have her privacy impinged upon like this, to be asked what, in any circle anywhere in the world, would be deemed a thoroughly insensitive question?

A different channel is replaying raw footages of her son's body – dead body, mind you – being pulled out of the ruins. The camera wastes no time in capturing the heart-breaking sight of his motionless body, as we, on the other side of the telly, eagerly swallow the tragedy unfolding in front of our eyes. This is reality TV at its best, after all, and we, an audience whose appetite for the sensational, the ghastly and the atrocious, knows no bounds, readily forsake all considerations of ethics and human decency in our desperate bid to feel connected.

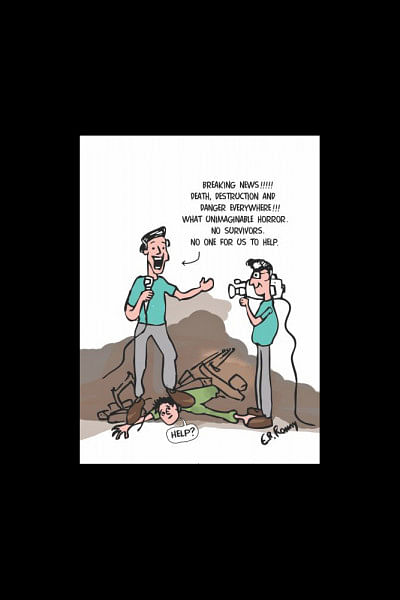

In yet another international channel, footages of a natural disaster is being played and replayed in a continuous loop; people's death and displacement are being broadcast – live – with the titillating header "BREAKING NEWS." In the comfort of our homes, miles away from the disaster, detached from the reality on the ground, we gulp down the heart-rending images of destruction, death and poverty, with or without popcorn. As I click through the '50 images that'll tell you everything you need to know about the X tragedy', I can't help but wonder: is there a perverse pleasure involved in the removed yet voyeuristic manner in which we consume such disasters? How is it that unspeakable tragedies are converted into highly lucrative, clickbait-worthy images and news for rapid mass consumption?

Lest all those who partake in the visual experiencing of such disasters take offence, allow me to clarify that my problem lies not with the fact that disasters are covered so widely – after all, one can argue that had the media not diligently highlighted the incidents, we would never know the extent of the catastrophes, and we would never be moved to act. What I do take issue with, however, is the way in which we cover what we call 'disasters' or 'tragedies', and how little consideration we show to the 'victims' of such incidents – the people whose stories we claim to be narrating and listening to. Beyond the politics of representation, there is also a need to question why we feel the urge to reduce what should be appalling incidents into spectator sports, and what the implications are of doing so. We need to explore if these 'sensational' stories hide more than they reveal by shifting our attention from the bigger, more critical – and less clickbait-worthy – stories about structural oppression and injustice.

Take the Haiti earthquake in 2010, for instance. The best reporters and photographers of the world raced to the disaster-laden country to tell us the "real" story about Haiti – a story of dismembered limbs, rescue operations and the healing power of foreign aid. What got left out of the Pulitzar-nominated stories, however, was how decades of colonial rule and neoliberal policies had made such extensive destruction from a natural disaster inevitable. As David Sirota wrote in the Huffington Post, "Rather than reporting on what made Haiti so poor and therefore its infrastructure so susceptible to collapse, we get clips of Haitians momentarily cheering 'USA!' as food packages trickle into their devastated capital. Rather than inquiries about how poverty made Haiti so ill-prepared for rescue operations, the disaster pornographers instead obediently follow George W. Bush, who self-servingly says, 'you've got to deal with the desperation and there ought to be no politicisation of that.'"

We can see a similar narrow pattern emerging in the Nepal earthquake coverage, with people's lives and deaths being filmed and telecast with the flash befitting a Bollywood production. Many Nepalese have begun to harshly criticise the Indian media coverage of the earthquake, terming it as jingoistic, paternalistic, sensational and highly disrespectful of the Nepalese nation and its people. #GoHomeIndianMedia was trending on Twitter, with posts such as "Dear @narendramodi thank for ur help but the shock of your media and army is bigger than earthquake," or "Your media and media personnel are acting like they are shooting some kind of family serials. If your media person can reach to the places where the relief supplies have not reached, at this time of crisis can't they take a first-aid kit or some food supplies with them as well?"

Our own media, too, has become increasingly adept at marketing disasters, going into extensive lengths to exclusively capture the 'tragedy', from shooting live footages as a person is hacked to death to making a critically injured arson victim pose in front of a camera, from dropping a mic down an abandoned well where a child is trapped to interrogating a child whose parents were both killed about their murder. During Rana Plaza, the media interviewed dying workers "LIVE" and went into the collapsed building with heavy recording equipment despite warnings that they might hurt survivors.

As the family members prayed, cried or sat still near the corpses of their relatives, too traumatised to betray any emotions, we, journalists, moved through the crowd, quickly but methodically, asking people who they had lost, if they had found the body, who the deceased or missing had left behind and so on. After a while, we'd only listen to the stories of those who had something "special" to add: three missing family members, perhaps, or two dead daughters, or an orphan who had lost both her parents in the incident. The rest of the deaths were deemed too ordinary, too commonplace, really, for front-page news. And this is the image that plagues me the most: running through the field of dead bodies, asking the devastated relatives first how many people they had lost before we engaged them in conversation, for the sake of efficiency. All those dead bodies, the mothers and sisters, the brothers and husbands, and their debilitating grief, was all just, to us, in the end, quotes to fill a 500-word story. The workers remained in death, as in life, nameless, faceless, disposable.

In attempting to make visible the cruelty of the world, these sensational narratives actually dictate the very limits of that visibility. They are five-minute package news that breaks the monotony of our alienated lives, that enables us to debate, condemn and moralise; but they never let us see the slain and wounded bodies, the structures of empire and violence.

Perhaps we are so drawn to these debilitating narratives because they make us shudder, they make us conscious of own humanity or our alienation from it. We are made aware of our power over the Other, while also being overpowered by what we see, feeling vulnerable at witnessing the Other's vulnerability. But the people whose lives and deaths we consume, remain, in the end, just that: Others.

The writer is an activist & journalist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments