Has an Indian 'man-eating tiger' been wrongly imprisoned?

A tiger in one of India's most visited national parks has been branded a killer and caged in a zoo, sparking protests from wildlife activists who claim the tiger has been wrongly accused and unfairly condemned to live out his life in captivity.

Is nine-year-old Ustad really a man-eater and if so, what made him kill? The question goes to the heart of the effort to boost the world's tiger population.

On 8 May Rampal Saini, a 53-year-old forest guard, was mauled to death by a tiger. It is claimed he was relieving himself in the tiger's territory when the animal attacked.

T-24, popularly known as Ustad was declared the prime suspect. The kill occurred in his territory and the large male tiger was spotted skulking near the man's body.

The tiger was one of the stars of the 400 sq km (98,842-acre) park.

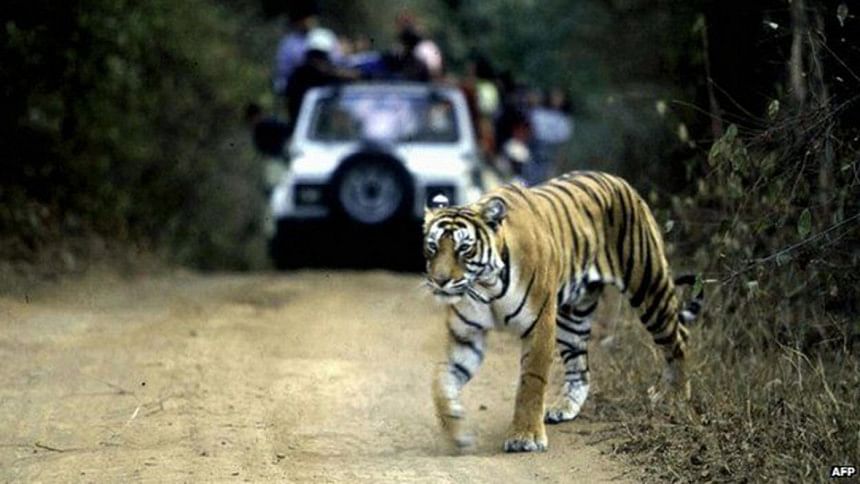

He was fearless and, to the delight of tourists, had been known to sit in the road, blocking the path of the jeeps that ferry visitors around.

Controversial decision

This weekend Ranthambore National Park, one of the most popular places in India for tiger safaris, took action.

Ustad was shot with a tranquilising dart, loaded into a cage packed with ice to keep the big cat cool, and driven to a zoo 400km (250 miles) away.

Now Ustad is caged in an enclosure smaller than a football field.

It has proved a controversial decision. Some wildlife activists say locking Ustad up is illegal and are campaigning to have him moved back into the park.

The Jaipur High Court is to hear a case brought by Chandramauleshwar Singh, a tiger lover and a regular visitor to Ranthambore.

He says caging Ustad is a breach of the Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972, which says wild animals can only be kept in captivity if India's chief wildlife warden is satisfied that they can't be rehabilitated in the wild.

Singh maintains that the evidence to make that judgement isn't available because, he says, the decision to move Ustad was made without "any scientific probe or investigation into the circumstance of the attack".

He argues that the attack on the guard was an aberration, that Saini was only attacked because he had trespassed onto the tiger's territory.

Ustad lived near a temple visited by thousands of pilgrims every day for almost eight years without incident, he claims.

Singh argues the real reason the park decided to move Ustad was because of pressure from the local tourist industry, which feared visitors would be frightened off by the presence of a man-eater.

And one of India's most respected wildlife experts supports the park's decision to relocate Ustad.

"In my 40 years of experience of the tigers of Ranthambore, T-24 is the most dangerous tiger I have ever encountered," Valmik Thapar told the Hindustan Times newspaper.

He paints a very different picture of Ustad's behaviour.

The tiger has a grim record of previous offences. The park says this is his fourth human kill.

T-24 was accused of killing a 23-year-old local man in 2010 and a 19-year-old boy in March 2012.

He is alleged to have struck again in October 2012, when another forest guard was savaged.

'Benefit of doubt'

And he is not just a killer. According to Thapar, the corpses of the villagers were partly devoured.

The only reason the tiger didn't eat the forest guards was because their bodies were retrieved while the tiger was kept at bay, he claims.

He says the problem is that Ustad has lost his fear of humans.

"After the first two kills I had suggested that this tiger be relocated to a captive enclosure but the tiger was given the benefit of the doubt," says Thapar.

The case raises questions for tiger conservation worldwide because India has been very successful in its efforts to increase its tiger population.

In January it announced that tiger numbers were up by a third, from 1,706 in 2011 to 2,226 in 2014.

Yet over the last century 93% of the habitat in which tigers used to live has been lost. Meanwhile the human population continues to grow.

That means people and tigers meet more often, occasionally with disastrous results.

More than 60 people are killed by tigers every year in India.

The fear is that the stories of man-eaters like Ustad will turn people against tigers, undermining the long-term conservation effort.

"Our feelings today must be for the families who suffered tragically in these five years that have gone by," says Thapar.

"Any person or group who believed that he should have not been relocated would have to bear the responsibility on their shoulders for the next human kill and the accelerating conflict that could result."

He is adamant that relocation is the right decision.

"T-24 was given the maximum benefit of doubt that any man-eating tiger has ever got in recent Indian history."

But ultimately it will be the court in Jaipur on 28 May that will decide Ustad's fate.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments