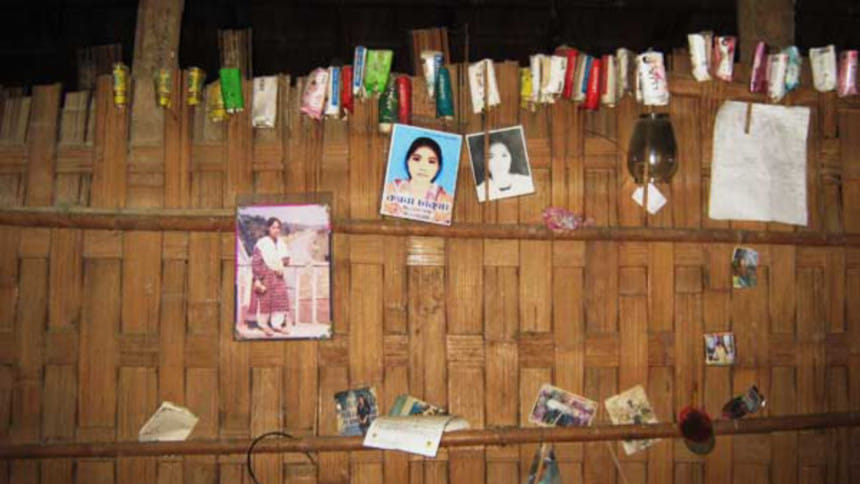

For the Kalpana Chakma I know and the one I never will

I never knew Kalpana di – not personally anyway -- the fearless indigenous activist who was snatched away from us by "mysterious" powers-that-be 19 years ago, when she was only 20 years of age. I've only known her through the breathing words of her diary, published as a book by the Hill Women's Federation; I've known her through those words that the state deemed too dangerous, through those nuanced critiques of patriarchy, ethnocentric nationalism and militarism, through her insistence that the struggle for liberation from Bangali oppression should not subsume the struggle for freedom of indigenous women from the dual oppression of patriarchy and ethno-centrism. I've known her through her brother, Kalindi Kumar Chakma, who -- still haunted by the last words of her sister, "Dada, mahre bacha!" (Brother, save me!) -- has waged a relentless fight for the last 19 years in the pursuit of justice for his sister, despite repeated threats and harassments from powerful quarters. I have known her from her comrades – both adivasi and Bangali – who keep her memory alive, through their protests, writings and exhibitions, and through their own work against the systematic oppression of adivasis in the CHT.

But I've also known her through – or despite – the careful manoeuvres to discredit her memory and deny her abduction. I've known her through the farcical show staged by the powers-that-be for the last 19 years in the name of justice, a charade that has made a mockery of the rule of law, and highlighted the ways in which the law can be made subservient to the interests of the powerful. I've known her through the deliberate attempts by the state, during numerous investigations, to erase the eyewitness accounts of her brother which claimed that a group of 12 army and Village Defense Party (VDP) men – including Lieutenant Ferdous, Saleh Ahmed and Nurul Haq (as named in the first FIR) – picked up Kalpana from their house. I've known her through the questionable report submitted by the Commission formed to investigate her abduction. A report which, kept hidden for fourteen long years of her disappearance, when finally published, insisted that she had been "willingly or unwillingly abducted." Because, apparently, willing abduction isn't an oxymoron.

The police reports, one submitted in 2010 and another in 2012, also made similar claims; they not only discounted the eye-witnesses and testimonies of indigenous villagers, but did not even question, let alone arrest, the main accused in the FIR. Kalindi rejected both the reports, and his lawyers pleaded for a judicial inquiry, stating that another police investigation was very unlikely to lead to a fair investigation. Not surprisingly, that request was turned down and another police investigation was ordered, with specific directives that the three named in the FIR be interrogated and their testimonies recorded.

Those of us who were at the hearing in Rangamati – did we really think that justice would finally be served through this new investigation, that the police would have the power to challenge the all-powerful institution that is given all but absolute impunity by the state?

Maybe the optimists amidst us still held hope, even after this long delay, in the rule of law, in justice, in the state's assurance that all lives are equally valuable. But, alas, the farce continued, as the date for submitting the report got postponed 22 times! A progress report, submitted to a Rangamati court last year, reads, "Since the key witness of the case is the victim herself… the investigation of the case cannot be completed until she is found." Through this claim, the state is essentially setting a dangerous precedent that cases of enforced disappearances cannot be resolved until and unless the victim is found! And why is Kalpana the only key witness to a case that had two eye-witnesses, her two brothers? The investigator in charge of the case did not even take the testimony of Lalbihari Chakma, who, too, had been dragged out of the house, along with Kalpana.

So far 35 investigation officers have investigated the case, to no avail. It's perhaps high time to conclude that no investigation conducted by the police would lead to an acceptable and fair outcome. If the state itself does not want the case to be resolved and the perpetrator(s) arrested, how can we expect an investigation officer, no matter how valiant and honest, to be able to do so?

19 years later, it's not only justice for Kalpana which remains outside of the reach of the adivasis. The promises made in the Accord, too, remain unfulfilled 19 years on, with incidents of exploitation of adivasis, violence against adivasi women, land grabbing by settlers and state institutions and curbing of dissent taking a more ominous turn with each passing year. Bangali settlers and law enforcement officers stationed there continue to enjoy impunity for crimes committed against adivasi communities. Dissent by indigenous groups is met with violence from different quarters. What would Kalpana have said, or thought, I wonder often, if she had lived to see the continued oppression of her people, even after "peace" has been established in the region?

I've only known Kalpana di in snippets, from conversations and debates, tears and struggles, state propaganda and alter-narratives. In all likelihood, I'll never really get to know her beyond these imaginings. But for as long as we are alive, a part of her will live with us who dream of a more egalitarian and democratic society, and with every indigenous activist who continues to fight for the freedom of the adivasis.

The writer is a journalist and activist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments