‘Forget princess, want to be astrophysicist’: Bangladeshi scientist at NASA becomes an inspiration

"Forget princess, I want to be an astrophysicist."

An excited young girl, wearing a T-shirt with these words, made Mahmooda Sultana's day.

The girl approached Mahmooda and said, "When I grow up, I want to be just like you. I want to work at NASA."

"She took a photo with me, which I treasure… She made my day!" Mahmooda recalled the incident which took place last year when she gave a talk at Baltimore middle school.

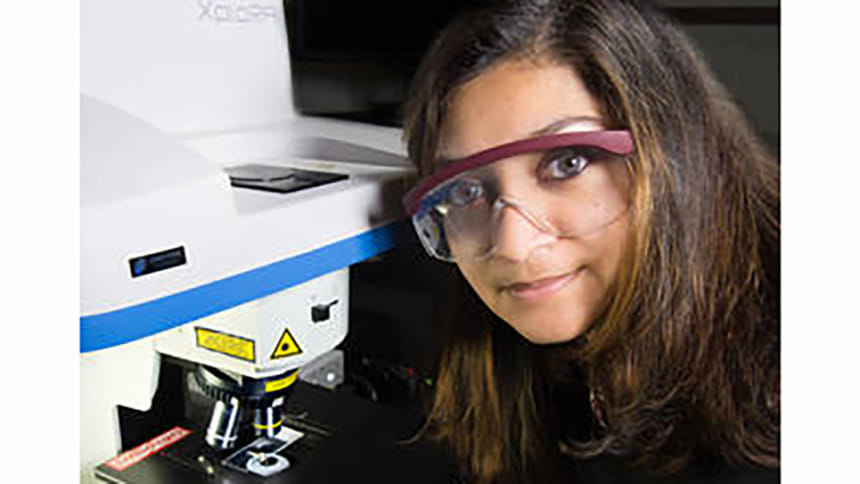

Mahmooda Sultana, originally from Bangladesh, is an award-winning scientist and former aerospace engineer at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, working at present as the associate head of the Instrument and Payload Systems Engineering Branch under Engineering Directorate.

She joined Goddard in 2010 after completing her PhD in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). At Goddard, she develops new instruments and oversees instrument systems engineering work on various flight missions of the space center.

She won the Goddard's Internal Research and Development Innovator of the Year award in 2017 for her groundbreaking inventions on nanotechnology.

"My current role allows me to contribute to Goddard's mission in many different ways. I help develop new instruments using cutting-edge technologies that enable new science missions. I also help provide supervisory oversight over the instrument systems engineering work on various flight missions and provide branch management support," Mahmooda said in an interview to Elizabeth M Jarrell at the Goddard Space Flight Center.

"I grew up in Bangladesh. When I was 14, my family moved to southern California," she said.

Mahmooda said her father, who worked as a civil engineer, inspired her to pursue science. However, she noticed a lack of women engineers in her community.

"My father was a supervisory civil engineer for the government. He built dams and barrages that controlled the water flow from the Himalayas and India to prevent flooding. He used to take us to the field and explain how the different components work. He let us play in the control room. That definitely got me interested in understanding how different devices worked."

"We lived in a community where all the government engineers lived together. All our neighbors were engineers. There was not a single woman engineer that I remember in that community of hundreds. My brain automatically presumed that women did not grow up to become engineers."

"My great uncle was a physicist at NASA's Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley. I loved hearing about his work. Growing up, I wanted to be a mathematician. I loved math, physics and chemistry. I wanted to be a mathematician or a scientist and work for NASA," she said.

Mahmooda graduated in chemical engineering, with a minor in math, from the University of Southern California. Later she pursued a PhD in chemical engineering on a fellowship at the MIT.

"By that time, I felt that chemical engineering seemed to offer the most options for future work," she said.

Mahmooda, however, noted that her parents were very disappointed that she did not choose to become a medical doctor.

"Their expectations had to do with cultural conceptions… The best students in South Asia typically go into engineering or into medicine. Sciences and arts are usually second choices. I thought I could go to college for chemical engineering and then go on to medical school. My parents really liked that plan. That is how I got into chemical engineering. But, once I was in it, I loved the discipline."

She also noted that her parents are now happy that she works at NASA.

"I went to a career fair at MIT in my final year. I had one resume left after distributing my resumes to the companies and research labs I was considering at the time. I saw the NASA Goddard booth and suddenly remembered how excited I was about working for NASA growing up. So, I decided to give my last resume to the then-associate branch head of the detectors branch, Thomas Stevenson."

"At first, he said that the detectors branch did not have a lot of opportunities for chemical engineers. When I described my multidisciplinary thesis work to him on micro electric mechanical devices, he was immediately interested. We had a follow up phone interview and I got a job at Goddard. So, it was quite serendipitous."

"Initially, I was part of a team that worked on the microshutter array for the James Webb Space Telescope. This array includes hundreds of little windows that can open or close to let light into the detector. The microshutter array was one of the most interesting projects I have worked on."

"My parents were quite proud that my work at NASA contributed to scientific knowledge and enabled new missions."

Mahmooda, who developed several new nanotechnology-based instruments for use on future space missions, holds a number of patents and have more patents pending in nanotechnology.

One of her inventions is a multifunctional sensor platform made of nanomaterials on a single substrate, which will be able to detect key gases needed for the origin of life, and can be used to explore habitability and life on other planets.

She is also developing a multispectral imager using quantum dots [nanometer-sized particles of semiconductors that have interesting optical properties].

Mahmooda also collaborates with several other organisations, including MIT, Northeastern University, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and LPS on some of her projects, and partakes in outreach initiatives to inspire more young girls to become engineers and scientists.

"I now give talks at high schools and middle schools sharing my journey to serve as an example to the young girls. I want them to know that they can become a scientist or an engineer at NASA too if that is what they would like to be in life," she said.

"Last year, I gave a talk at a Baltimore middle school. After my talk, a young girl approached wearing a T-shirt that said 'Forget princess, I want to be an astrophysicist.' She took a photo with me, which I treasure. She said, 'When I grow up, I want to be just like you. I want to work at NASA.' She made my day!" Mahmooda added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments