Where is our RMG sector headed?

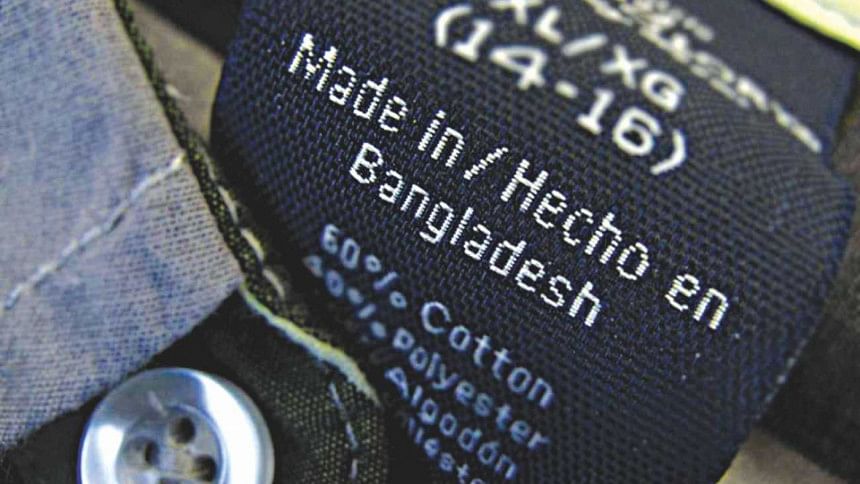

The second Apparel Summit recently took place in Dhaka, on February 25, after a series of dramatic and consequential events. It reflected the tensions of the protests in Ashulia that spurred the debate between illegal work stoppages and disregard of labour rights and dignity. The incident not only tarnished the image of the RMG sector and the country, but also substantially ruined the platform for dialogue between employers and workers. This was observed by the letter sent from 11 members of the US congress to the Prime Minister expressing concerns over the harassment of labour leaders and the near boycott of the summit by five top brands that account for majority of RMG exports from Bangladesh. Thus, the discussion among panelists at the event was definitely food for thought to understand where the RMG industry stands at the moment and what the future will look like for a sector that accounts for about 80 percent of the country's exports and employs more than four million people.

Naturally, during the discussion, the initiatives taken to improve the structural and fire safety of the garment factories in the aftermath of the Rana Plaza collapse were highlighted. The success of the work of Accord, Alliance, the National Action Plan, and ILO portrayed the sincerity of entrepreneurs and the government in making the sector more transparent and compliant. In addition, the minimum wage of RMG workers was increased from BDT 3,000 to BDT 5,300. Hence, shifting the scenario from a potential massive setback for the sector to now heavily driven towards a realistic export target of USD 50 billion by 2021.

However, this resulted in another debate: how will the remediation work be financed? This brings about the issue of fair prices or sustainable sourcing. This means that buyers will pay more as the cost of doing business becomes higher due to investment in compliance measures. Now, this is contrary to the business practice of profit maximisation, as the price of the end product is decided by consumers. Therefore, a structure of competition is created in the supply chain causing a race to the bottom which hampers labour wages and rights as buyers will have to source from more economic destinations. Furthermore, there is the question of whether the minimum wage is the living wage and whether increasing it will result in an inflationary pressure, causing further rise in prices of rent and commodities and possibly reduce competitiveness.

These concerns have made the government and the RMG entrepreneurs advocate strongly for a level playing field. This means rules that apply for the structural, social and environmental compliance in Bangladesh should be adopted in other major RMG exporting countries. It will prevent any unfair competitive advantage they will have through manufacturing cheaper products by ignoring those standards. This is a justified claim because despite the efforts made by government and RMG factory owners in the last years, any error or mishap has been received with substantial negative international press placing an undue pressure on the country and its economy. Contrarily, very little is spoken of competitor countries that are yet to take on similar initiatives matching the scale of Bangladesh. However, it is also noteworthy that the existence of Accord and Alliance that ensured transparency in the sector has presented Bangladesh as a relatively more reliable destination for sourcing, thus giving the industry an upper hand. Therefore in the discussion that has emerged about what is the way forward after the expiry of these programmes in 2018, it must be understood that it is imperative, should a new local initiative succeed Accord and Alliance, it has to be as effective and internationally acceptable as its predecessors.

Finally, it cannot be denied that in addition to the continuous sincere efforts of the entrepreneurs and the commitment of a hardworking labour force, the rapid expansion of the RMG sector is also due to the support it received nationally and internationally. These are tough cash incentives, access to resources in low cost such as gas and water by the factories, bilateral agreements with 28 countries and the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) of the European Union. As Bangladesh is a Least Developed Country (LDC), it enjoys duty and quota free access to the EU market under the Everything But Arms (EBA) provision of the GSP. This will cease to exist after the country graduates from LDC status, potentially by 2024.

In order to continue to receive zero duties after that, the country will have to apply for GSP+, meaning the country will have to ratify and effectively implement 27 core UN and international conventions. In addition, the country will have to accept without reservation reporting requirements imposed by those conventions and cooperate with the extensive EU monitoring procedure. Of the 27 conventions, Bangladesh is yet to ratify the ILO convention concerning "Minimum Age for Admission to Employment", and has often failed to provide timely reporting on the implementation of the ones it already ratified. Although this transformation is a matter of the next decade, yet consistency, coherent policy making, and maintained stability are fundamental to keep on this rapid expansion by enabling investments in the RMG sector in order to avoid any trade shocks and achieve the USD 50 billion USD export target on time.

To sum it all up, the RMG industry has come a very long way and has tackled major hiccups. Nevertheless, the road ahead is very challenging and to keep this sector vibrant, the stakeholders need to act simultaneously and coherently. There will have to be significant focus on reducing operational costs through efficiency in using resources such as gas, electricity and water. Workers will need to undergo skills development training to increase their productivity and a new set of home grown middle management will have to be developed who will be effective and compliant, enabling retention of the export earnings within the country. The RMG factory owners will have to collaborate with the international community in that regard in order to ensure effective technology transfer. There is also the need of social dialogue between owners and labour representatives to mitigate conflicts and reach common grounds. Both national and international media will have to be engaged to highlight the achievements of the sector. Finally the government must maintain stability and a favourable investment climate to finance infrastructure, in order to ensure efficiency and increase capacity of both production and transportation of goods, and also sustain an exchange rate regime that will keep our competitiveness. Last but not the least, the government will have to safeguard the rights, livelihood and dignity of the factory workers, and work to make their voices heard as they are the life and blood of the Bangladeshi RMG industry.

The writer is a development practitioner.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments