Is Depreciation Warranted?

If China can devalue its currency, why can't Bangladesh? The answer lies in market power which has snatched substantial part of the manoeuvring capacity of the central bank to manage the exchange rate. The central bank cannot take actions that go against market signals. Nor can it change the long term value of the currency by resorting to short term opportunistic interventions of buying, selling, and sterilisation in the foreign exchange market. The market is cruel enough to recover the true value of any asset, including currencies in the long run.

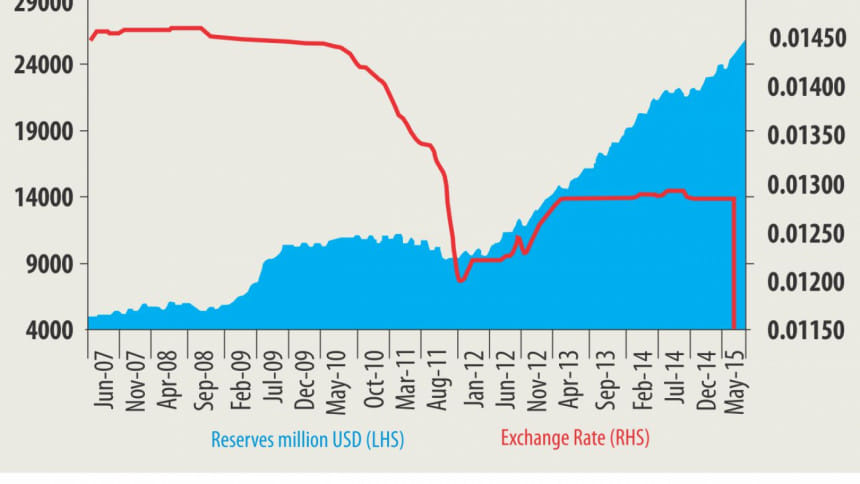

While Chinese and Indian currencies are depreciating, there seems to be a pressure for the taka to appreciate, especially since January 2012, as shown in Figure 1, leading to a higher exchange rate where the taka will be able to buy more dollars and euros than before. In theory this sounds interesting as the taka will become stronger than it is now when compared to the US dollar, but the results have been mixed. We need to start from the concept of the exchange rate to interpret these mixed impacts on exports and imports owing to any move in the value of our domestic currency.

Although there are two ways to define the exchange rate, the best way to define it is to determine the amount of the foreign currency that one unit of the domestic currency can purchase. Simply, the amount of the US dollar that Tk 1 can buy is the exchange rate for Bangladesh. If we need to spend Tk 80 to buy $1, the exchange rate in Bangladesh will be 1 over 80, equalling 0.0125 as shown in Figure 1.

The benefit of defining the exchange rate this way is to relate the term 'depreciation,' with a fall, and the term 'appreciation,' with a rise in the number. Economists like Paul Krugman, Oliver Blanchard, and Gregory Mankiw followed this, as students find it to be a straightforward and comfortable definition, while economist David Romer followed the inverse style, which is often confusing. Say tomorrow we need Tk 100 to buy $1- this makes the exchange rate 1 over 100, i.e. 0.01, which is clearly a depreciation because 0.01 is less than 0.0125.

Having defined the exchange rate this way, expectations have risen to see depreciation of our taka in the backdrop of depreciation of the Chinese yuan or the Indian rupee. If depreciation does take place, the domestic currency, taka, becomes weaker before the dollar, making our exports cheaper, therefore, leading to an increase in foreign demand for Bangladeshi garments. Thus, depreciation fuels export competitiveness and that is why exporters often lobby for depreciation.

Importers, however, represent the other side of the coin, and they dislike depreciation which erodes their purchasing power of foreign goods. The best way to avoid criticism from either side is to authorise the market to determine the exchange rate based on the demand and supply of the foreign currency. And the exchange rate which Bangladesh Bank determines now has been largely market-based since May 2003, although the central bank irons out fluctuations to maintain stability in the exchange rate so that foreign investors feel confident while investing in Bangladesh.

We call this the 'managed float', while the Western world termed it the 'dirty float.' If the supply of the dollar, for example, is greater than its demand, excessive supply of the dollar will reduce its price, making the taka stronger even though the bank or the government has done nothing to deliberately pump the value of the taka. In another situation, if the euro loses its value against the US dollar, the taka automatically becomes stronger against the euro, since we are pegged to the US dollar. Both these incidents have taken place recently, making the depreciation of taka almost impossible.

The supply channels of the dollar are now stronger than those the demand channels. We have a $10 billion trade deficit and almost a $6 billion service deficit, our remittances amounting $15 billion eventually help us land on the current account deficit of more than $1 billion - less than 1 percent of the GDP and thus, easily manageable. The dollar glut that we are facing is mainly attributable to our burgeoning capital and financial accounts, which have been net receivers of billions of dollars in the recent past. Since our domestic lending rate, close to 12 percent, seems very high to domestic investors, they have resorted to London's lending rate close to 5 percent, and thus have kept on borrowing foreign funds to reach $5 billion. In addition, we have foreign direct investments and trade credits.

These huge balances in capital and financial accounts easily eclipse a meagre current account deficit, ultimately ballooning the overall balance in the balance of payment. The overall balance has been between $4 to 5 billion in the last three fiscal years. And this amount has been added to the previous year's balance of international reserves, making it healthier than before.

Figure 1 shows how our exchange rate has been on an appreciating trend since January 2012 – a timeline that marks the dawn of vigorous growth in foreign reserves. A positive relationship between them is obvious. This scenario makes the taka stronger and exerts an appreciation stimulus on the exchange rate. Mega infrastructural investments and further liberalisation are needed to check this appreciating pressure on our currency. While India or China share different scenarios, following their steps in depreciation would be akin to going against the stream of market forces and thus, is unwarranted.

The writer is chief economist of Bangladesh Bank.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments