Health impacts of coal-fired power plants

What is the most important resource for a nation? Not natural resource. If that was the case, Nigeria, Angola, and Iraq would be developed nations by now. On the other hand, look at the most developed nations in Asia like Japan, Korea, and Singapore. They have one common factor: lack of natural resources. This shortage forced them to develop the best resource on earth - humans. Many envy their rapid development. Can this be replicated in other nations? The answer is yes, the replication is underway in countries like Bangladesh.

Dominique Lapierre, in his famous book City of Joy, described East Bengal, now Bangladesh, as a dejected wetland, devoid of any hope without the city of Kolkata. Notorious warmonger Henry Kissinger termed it a basket case as Bangladesh emerged from 215 years of systematic resource diversion and negligence by British and Pakistani rulers. In only four decades, the country has defied the naysayers, emerging as a miracle economy and a development role model that many nations envy today. The same theme that helped develop Japan, Korea, and Singapore, is in play – human potential. Proper appreciation and nurturing of this human potential has serious development consequences for aspiring nations like Bangladesh.

Rapid development brings its own challenges. Rising power demands that outpaced prediction is one of them. Policymakers have been scrambling to meet the exponentially rising electricity demand. This can lead to a dangerous path – too much focus on short-term needs that leads to the kind of planning that could handicap long-term growth. One such handicap is the destruction of public health through pollution from haphazard planning, leading to costly healthcare and lost productivity in the long run. I am talking in particular about advocating coal-based power plants for short term cost savings, which is too expensive for public health in the long run. When developed nations, like the United States, set up their coal based power plants, they did not have data on long term public health consequences. Fortunately, we do. From their data, we can predict the long term public health and economic costs for a densely populated country like Bangladesh.

Coal-fired power plants pose the greatest public health risk among all industrial sources of air pollution. Their emissions contribute to global warming, ozone smog, acid rain, regional haze, and, the most consequential of all, fine particle pollution. Trans-border pollution will also have serious public health consequences for northeast Indian states. While human movements can be checked through barbed wires, there is no cost-effective way to tame migration of pollutants across national borders. It's imprudent of India to help set up a series of coal-fired power plants inside the borders of its nearest neighbour.

Coal pollution has multiple dimensions that can have multiplier effects on each other. Irreversible chronic harm is caused by air pollutants like sulfur dioxide, particulate matter and nitrogen oxides. Sulfur and nitrogen oxides further react in ambient air, forming secondary fine particulates, while nitrogen oxides are also a precursor for ozone. Inhalation of particulate matters can adversely affect the brain, respiratory system, cardiovascular system, and blood. Coal plants also emit heavy metals and organic pollutants like mercury, led, arsenic, beryllium, chromium and dioxin. These can damage the developing nervous system of children in addition to causing cancer, hypertension, anemia or other cardiovascular diseases. These pollutants affect almost every system of the body, potentially wrecking havoc on public health. The harm will be more pronounced in people who get lifetime exposure from birth.

Heal and Environment Alliance estimates the public health cost of coal pollution in the European Union to be as high as 53 billion Euros per year, even without counting the lost working days. The estimates include 18,200 premature deaths, 2,100,000 days of medication, 4,100,000 lost working days, 28,600,000 cases of lower respiratory symptoms. Clean Energy Taskforce estimates the public health cost of coal plants to be more than $100 billion in the United States. The public health toll can be a lot higher, in terms of incidence for a densely populated country like Bangladesh. Population density in Bangladesh means a larger number of people will be affected by each plant, compared to Europe or the United States.

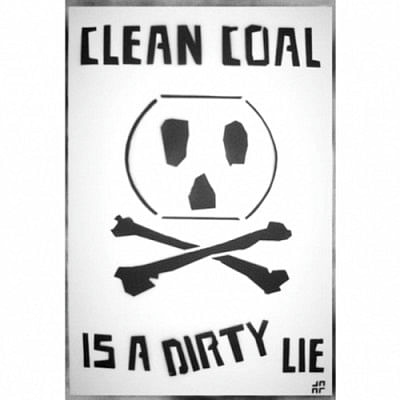

Coal companies are facing what cigarette companies faced before; increased pressure to cut down pollution. Peabody Energy, the largest coal energy company in the US, has recently declared bankruptcy due to rising public awareness and resulting regulatory burden. These coal companies are deploying the same arsenal as cigarette companies; pushing harder into the developing world. They are using marketing gimmicks like "clean coal", "CCS technologies" or "high efficiency coal". These are buzzwords devoid of substance, like "healthy cigarettes".

Nothing is more important for the long term growth of a country than a healthy productive workforce. The recent debate on coal based power plants has largely missed this point – the long-term public health consequence of coal based power plants. India is targeting 100 GW in solar generated power by 2022, which is 10 times the current demand of entire Bangladesh. Their plan includes 40 GW for rooftop solar power systems, which is four times our national demand. Bangladesh can take cues from these plans and follow suit.

These coal plants will pollute the environment for many generations to come. Children born under the coal polluted environment will face developmental challenges and lifetime health issues. They will have to bear additional sufferings, high health costs and substantially reduced earnings. Recent debates on coal power have focused on saving the mangrove forest, global warming and environment. However, it ignored the elephant in the room – multi generational public health costs.

Future generations will bear the burden of pollution caused by short-sighted planning. Policymakers and concerned citizens need to have a hard look at the burden we pass on to our children, grandchildren and their children with the setting up of coal-based power plants.

The writer works for a biopharmaceutical company in Boston. He received his PhD in Biostatistics from Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments