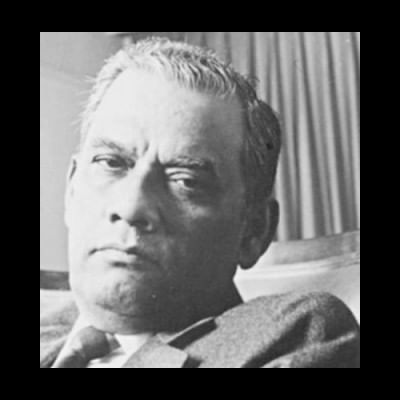

A lighthouse has gone dark and silent

Iowe him my first job, the memo-writing skills, the vast concourse of discourses on virtually everything on earth, and roughly half the books in my collection. And when AKN Ahmed died of a stroke on February 24 in a Washington DC hospital, this entire inventory wobbled like a miserable prop bereft of its support. Death took more than a man last Wednesday. I personally lost a bulwark against this mad, mad world.

Except for the first six years when I studied in Washington DC, ours was a long distance relationship, spanning more than 35 years. Every time we met, our conversations quickly veered towards serious discussions. AKN Ahmed was the most avid reader of books I have known, switching from one book to another in one conversation faster than some of us could turn pages in a book. During the visits, whether he was in Dhaka or I was in Washington, he gave me at least a dozen books every year, and if you multiply it by the number of years we knew each other, that many books I have received from him over the years.

When Mr. Ahmed retired as the second governor of Bangladesh Bank in 1976, he had almost half of his life left ahead of him. He told me when I met him last August in his Watergate apartment that he was pushing 92. Before I left, he hugged me and told me it could be the last time we were seeing each other. He walked with me to the corner of the Watergate complex and stood there until I crossed the road to The George Washington University campus on the other side.

His son Ruben Ahmed introduced me to AKN Ahmed in 1981. By that time Mr. Ahmed had moved from London to Washington as the chief economist of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International with his imposing office in the US capital. In the early 1950s, he worked in The World Bank, and in the mid-1970s, he served the International Monetary Fund as an advisor. He was simultaneously the Bangladesh ambassador to Japan and Korea in the mid-1980s.

Three to four years ago, Mr. Ahmed amusingly told me that he had decided to move from Dhaka to London because all his friends were there. Afterwards, he decided to move again because he had realised that most of his living friends were settled in the United States. Then he said he was ready to move again because all his friends had migrated to a new country, and bobbed his index finger up and down in the air pointing at the sky.

AKN Ahmed was the only person I have known who lived to think but didn't have to think to live, because, as he told me once, an invisible hand always pushed him to the next slot. He believed in the grand design of things and success to him depended not on attainments but on attempts. Mr. Ahmed fathered a number of organisations in his lifetime, but he resented that most of them died and the surviving ones were deformed. His latest disappointment was BASIC Bank, which was his brainchild and of which he was the first chairman. I quipped that in his days the chair made the man, but now the man makes the chair.

He had spent almost one year in captivity in Pakistan between 1971 and 1972, but he wasn't as stricken as he was during each one of the three crises in his life. First was when he decided to resign as the governor of Bangladesh Bank in 1976. It was around this time that he had suffered a heart attack that required him to undergo a cardiac bypass surgery.

The second agonising crisis was when the Bank of Credit and Commerce International collapsed in 1991. He was subjected to an FBI investigation, which eventually couldn't link him to any wrongdoing. He told me he never feared that he was going to be implicated, but the sheer irritation of being under the scanner tested his patience.

The third crisis left him reeling for the remaining days of his life. His daughter Ramina's untimely death sucked the life out of him, after which he lost the zest for life. The man who analysed everything and left nothing to chance was confronted with a void that couldn't tell him why he deserved such a cruel hand of fate.

Even then, he was like a lighthouse until his last breath, beaming across the sea on stormy nights. He never stopped reading books and sharing his erudition to help others organise their thoughts. He wrote a number of books and articles, forever keen to dispel confusion in other minds. His mastery of subjects and the clarity of his thoughts were impressive. He could explain even the most complicated things in simple words. He was my rescuer every time I felt lost.

Last time I talked to AKN Ahmed was about three weeks before he died. I promised to call back after he returned from his trip to Florida where Ramina's daughter had given birth to her first child. The trip must have brought him some kind of a closure, after which he couldn't care if he lived or died. The eternity has lost a speck of dust, the world a headcount, the country a worthy son, but I have lost a lodestar in the sky.

The writer is editor of the weekly First News and an opinion writer for The Daily Star.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments