LUNCH AT THE RESIDENCE

Dhaka, August, 1974

Faruq (Faruq Chowdhury, former ambassador and foreign secretary) and I were on holiday from his duties as Deputy High Commissioner in London.

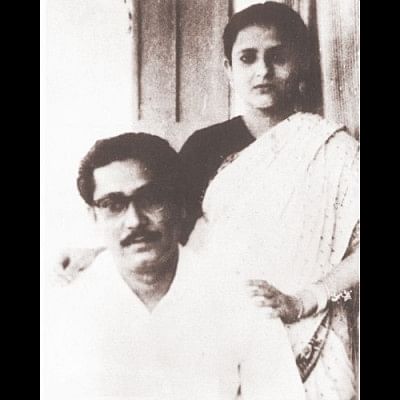

The phone rang at midday at Surma House where we were staying. The phone call was for me and the caller was Begum Mujib, wife of the honourable Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. "Bhabhi, do come for lunch tomorrow -- both Faruq bhai and you." Then she added, "Bhabi, what would you especially like to eat?" To say I was completely overawed would be putting it mildly. I was immediately struck by her affection and warmth.

The next day Faruq and I arrived at Rd. 32, House 10, Dhanmondi - the residence of the honourable Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family. Begum Mujib greeted us with a smile as we entered the first floor. She ushered me into a small ante-room. Kamal her eldest son attended to Faruq. There was another lady present in the small ante-room. She was puffing away at a cigarette. I was curious. Begum Mujib introduced her to me as one of her very close friends. There could not have been a bigger contrast between the two. Begum Mujib -- demure, her head covered with the anchal of her saree. This lady nonchalantly smoking one cigarette after the other. I myself was clad in a silk sari with my shoulders covered and my very short hair pinned below a false bun or khopa. Interestingly, the conversation turned to the latest hair styles young ladies were sporting in new Bangladesh. Begum Mujib affirmately stated, "I really don't like short hair at all, not at all feminine". "Bhabi," I blurted, "I have very short hair, I pinned it up because I was coming to the prime minister's house, this khopa is all false". Begum Mujib laughed and said, "Don't worry bhabi, everything looks alright on you". I was relieved. Again she asked, "Bhabi, what sort of saris do you like?" I replied, "Cotton saris, I can't have enough of them." Immediately, Begum Mujib turned to Rehana, her youngest daughter, and said, "Go bring some nice sarees of mine for this bhabi", pointing to me. Rehana came back with a bundle of sarees. Begum Mujib chose three cotton and one brand new silk sari, and presented all four to me. I was overwhelmed by her generosity.

Then the conversation took another turn - people in power and people out of power. Begum Mujib turned to me and said, "You know bhabi, all these people surrounding me now, singing like Koels (nightingales), they will all disappear the moment your brother is no longer in such a position. Where were all of them the nine months your brother was in jail in West Pakistan? That is why I now look at them and don't say much." I really did not know how to answer as we had never been in power; all of us were children of government servants married to children of other government servants.

Lunch was served and we all walked into the dining area. The table was covered with a plastic table cloth, very much like our own dining tables. I immediately noted the variety of food I had especially asked for. There were many types of bharta including shutki bharta, fish, both small and large. I was not a meat lover, but for Faruq, there was chicken and beef. Again I was touched and flattered. Both Faruq and I sat on either side of Begum Mujib. She plied us with food. The "cigarette" lady sat at the bottom, still puffing away. The children Kamal, Jamal and Rehana joined us. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib was away, overseeing the food ravaged districts of Bangladesh.

At one point during lunch, a young man entered. He greeted Begum Mujib as chachi, glanced at the rest of us and said, "Before you ask me, I will of course eat with you; but when chacha comes I will not speak to him." I thought that this was very rude. Moreover, he appeared over confident and very brash. Then he looked at the "cigarette lady" and addressed her as ma. She was, I gathered soon enough, his mother-in-law.

Suddenly there was a gust of wind, a door opened and there in front of me stood Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, extremely tall, handsome and charismatic. Since then as a diplomat's wife I have seen many of the world's leaders, but I have never again in my life seen so much charisma emanating from one person. The very walls seemed to stretch outwards as if to accommodate him. He just completely filled the room. Such was his presence. His eyes were very red, as if filled with tears. He turned and said, "It is too terrible, my people are suffering so much and there are only twenty four hours in each day. I have to do something, anything to relieve them of their plight." Then he turned and went into his bedroom asking Faruq to follow. He wanted to discuss relief material for the worst affected people.

All of us were silent; the brash young man had disappeared as soon as he saw Bangabandhu. After fifteen minutes, I heard a cry "Jeena, Jeena come here, I want to talk to you". The prime minister was calling me, I wondered why? As I entered he said, "I believe you don't want to come back to Dhaka, so how will your husband help me?" I in turn mumbled, "Bangabandhu, I have one year left for my graduation (I was doing BSc in Sociology at London University) and if I don't complete it, I cannot help my children if anything should happen to their father."

Bangladesh at that time was filled with war widows, living in insecurity. There were no jobs unless you were a graduate. The prime minister looked at me and heaved a sigh, "Yes, you are right. I will call Faruq back in a year's time; are you happy?" I was so relieved as I murmured my thanks. Then he saw me glancing towards his feet, all tucked in crosswise, as he sat on the bed. Now it is common custom for younger people to touch their elder's feet before leaving. I was just imagining how I could do that, no feet were visible.

"So what is troubling you now?" the prime minister asked.

"I cannot see your feet, how will I touch them before I leave?" I replied. For the first time he laughed and said, "No need for that, I will give you my blessings anyway".

We left soon after. As the car turned the corner I curiously asked Faruq, "By the way, who was that brash young man?"

"That was Major Daleem."

8 PM, London, August 14, 1975

I had got through my exams, and Faruq was asked to join President Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's secretariat a few weeks later. We were all packed and ready to leave for Bangladesh in a couple of days. I had just picked up my BSc certificate from the university and was a little late coming home. As I entered, I saw Faruq talking to Viqarul, a very good friend. I greeted them and proceeded upwards to our bedroom. I had a very uneasy feeling; I came down and said ominously, "I just feel something really terrible is going to happen." Both of them said, "Zeena, you and your premonitions!" Soon after we had dinner, Viqarul left and we went upstairs to sleep.

4 AM, August 15, 1975

The phone rang shrilly. Faruq caught the phone, put it down and started howling loudly.

"All of them killed, the entire family gunned down, I cannot imagine Bangabandhu is dead, BBC has just informed me. I have to go to the office now."

And how did I feel? That towering personality, killed by his own people. Begum Mujib, so loving and affectionate. The sons and their wives, newly married, little Russel, ten years old, all gunned down.

Just then the phone rang again. It was Hasina, "Bhabi, I know my whole family has been wiped out". She was calling from Brussels or Germany. (Hasina and Rehana were visiting Europe at that time). "Tell me," she asked desperately, "My little brother Russel, is he dead? I brought him up Kolay, peethay". (In her arms she meant) I lied as I replied, "No, he is alive." I just could not tell an anguished elder sister that the killers had spared no one.

Then another bizarre phone call came "Zeenat," said a voice on the line, "I am Naseem, is there anything I can do to help?" It was Naseem Aurangzeb, daughter of President Ayub, Pakistan's president for ten years, who I had met a few days earlier.

No one else called. I remained stunned; silent, trying hard to mutter some prayers. Faruq returned a few hours later. He answered my mute question, "The coup was carried out by a renegade unit of the army." Then I voiced another question, "But who were directly involved in the massacre of the whole family? Anyone we know?"

"Yes," he replied. "Major Daleem."

In Memoriam

Readers please note that the author of this tragic recollection herself now lives in Road 32, House 14, Dhanmondi, a couple of yards away from "The Residence", now a museum dedicated to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family, so brutally, mercilessly massacred that "Sharoday Prathay" - August 15, 1975. She poignantly remembers that "lunch" so lovingly served by Begum Mujibur Rahman, and especially her encounter with that towering figure -- Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

The writer is an educationist and Owner/Prinicipal, Kids Tutororial School.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments