Mammaries of the socialist raj

The people caught most unprepared by the PM's strike on currency are the bureaucrats. The problem: They've been there, done that.

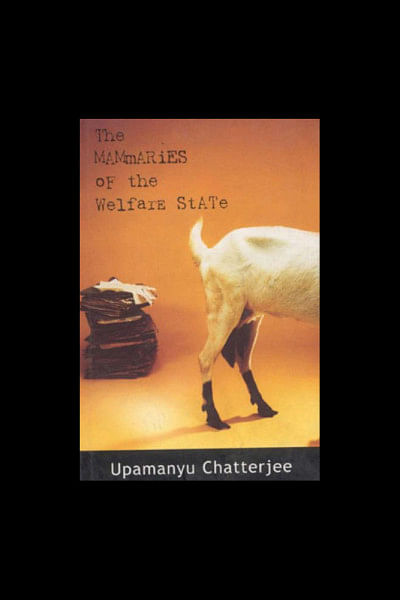

The headline of this week's National Interest doesn't suffer from a mischievous typo. Nor do I claim to be inventing that expression. It isn't even a cheap, but tempting, pun on the way true Punjabis would often pronounce "memories". I wouldn't dare, having started to learn English (from Standard VI, as was the norm then) from that notorious centre of academic excellence called Bhatinda in 1966. I am, in fact, borrowing it from The Mammaries of the Welfare State, the much-acclaimed work of formidable civil servant Upamanyu Chatterjee.

Both Bhatinda, and the year 1966, however, have something to do with this and not because "via Bhatinda" has been the familiar old way to mock somebody for having acquired his academic degrees in a twisted way. It is because this is where Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Friday made a spirited defence of his demonetisation, or "war against black money and corruption" while laying the foundation stone of a new (and genuine) All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS). The year 1966 becomes relevant because that is when Indira Gandhi became prime minister and started building our deepest "socialist" state. She inherited a post-war, chronically famine-struck shortage economy and launched the toughest, roughest and the most irrational rationing in our history.

People put up with it stoically for some time, accepting the reality of ship-to-mouth existence. But within a couple of years, it had gone too far as the bureaucracy discovered more inventive forms of rationing, controls and enhancing its own power. District magistrates (DMs) were empowered to grant sugar quotas for weddings; maida (white flour) and sooji (semolina) were then added to the list. Kerosene was already rationed. Cement, too, joined the list (and it was the last one to go). The citizen's view of this government was conditioned by the quality of rationing management. Not surprisingly, the most popular anti-Indira slogan of the Jana Sangh (the BJP's older avatar), was: "Indira tere shashan mein, kooda bik gaya ration mein (Indira, in your reign, even garbage sells at the ration shop)."

Undeterred, however, the socialist state marched on. By 1970, cheaper, dull-coloured — may be inspired by Mao suits — cotton was also sold on ration cards. At one point there were school notebooks as well. The civil service felt more and more empowered. They had the power, for example, to determine how many guests you were to reasonably expect at your child's wedding and how much halwa you should feed per barati (no halwa without sooji and sugar). Until the socialist sarkar brought in its guest-control order, limiting the number to a virtuous 25 at a wedding. Of course, nobody followed it, and soon an arbitrage built, where inspectors charged you per head by the number of additional guests they let you feed, just as the caterer might bill you for feeding them. The crowning glory of the shortage economy was the ban on khoya (reduced milk) and other milk products, including paneer, barfi, gulab jamuns and rasogollas during summer months when milk was in short supply.

The promise of the socialist raj was to bridge the gap between the rich and the poor, the ruler and the voter. The result was the exact opposite. The rich continued to get richer, and happily bought (or rented) their way out of the system while the rest were resigned to being colonised by the bureaucracy. We even learnt to laugh at our misery. Example: A farmer (in Bhatinda, where else) applied for a licence for a cannon. The DM asked to see who this nutcase was. "Huzoor," the farmer said earnestly, "When I applied for five quintals of sugar for my daughter's wedding, sahib bahadur (the DM) had allotted me 25 kg. So, now I just need a licence for a pistol, but better to start with (applying for) a cannon."

Or there was Bollywood, with a string of Manoj Kumar-style hits that had the hoarder, black-marketeer, profiteer as the bad guy, villain, murderer, even rapist, but never a bhadralok officer. Google the 1974 superhit Roti, Kapada Aur Makaan, which coincided with our historic inflation peak of 27 percent. Check out its evergreen song "baaki kuchh bacha toh mehngayi maar gayi..." How familiar Verma Malik's lines seem now when we queue up to draw a little bit of the latest item on rationing: Currency notes, from our own bank accounts. The song goes on: "Ration mein jo lineke lambayi maar gayi/Janata jo cheekhi chillayi maar gayi (endless ration lines kill us, and if they don't, just the pain of protesting kills the masses)."

The decades of socialist rationing created super (sarkari) elites within a society that was always brutally unequal and also generated the most corruption and black money. It is fashionable to self-flagellate and say, we Indians are like this only, genetically designed to be dishonest and corrupt. The fact is, we aren't perfect, but our establishment, or the state, our leaders and in short the "system" left us no chance through these decades of socialist self-destruction. In our most state-controlled garibi hatao years, during 1971-83, there was zero decline in the percentage of people below the poverty line. But such was the majesty of the socialist raj that we still hang on to its memories and hail Indira Gandhi as our greatest leader.

The post-Google generation may have no connect with this, but their parents do. As does our bureaucracy. That's why any thought of fresh rationing and controls is mouth-watering. It also brings back the old, socialist, control-raj basic instinct. So what does the "system" do when surprised by demonetisation but dust out old manuals: Rs 4,000 per head with ID photocopies. Then, as too many come in, indelible ink. When that's not available in a hurry, halve the limit. Still can't manage, withdraw, never mind the prime minister and the RBI both promised they won't until December 30. The state always knows best. The initial list of evidence for drawing Rs 2.5 lakh of your own money for a wedding was drafted by the same person who wrote the wedding sugar allocation rules in the sixties — maybe even literally so, as someone merely pulled out something from the archives and filled in the blanks. This requires more research and detail than is possible in a mere column, probably even a Harvard Kennedy School doctorate on how Indian bureaucracy thinks. Each decision taken since November 8-induced panic harks back to a tried and discarded practice of the socialist past.

You still have doubts, check your old passports. Not too old, in fact, anything until early nineties when P V Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh reform changed things. The last few pages would be soiled with clumsy, mostly illegible entries, rubber stamps and all, by bank clerks listing exchange issued to you for foreign travel (on RBI permits printed beautifully on currency-grade stationery), then exchange brought back and refunded to the bank and so on. And what did our "system" just do to "facilitate" poor foreign tourists who were stupid enough to come to India and get caught in this man-made currency famine and rationing: Offer them Rs 5,000 (USD 71) per week while similarly soiling the backs of their passports. When in doubt, or in panic, and short of ideas, go back to the past, however awful and discredited. You won't doubt Prime Minister Modi's determination to change India. You'd doubt, however, if he can do so by using the same old bureaucracy hanging on to bountiful mammaries of the socialist raj, which fed corruption and black economy in the first place.

The writer is an Indian journalist.

Twitter: @ShekharGupta

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments