A narrow spectrum of debate

"The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum."

–Noam Chomsky, The Common Good (1998)

Sometimes it seems that Bangladeshis have been debating the same thing over and over again, failing to reach any consensus and only driving deeper wedges between the people. Consider that the headlines of the past decade are not very different from the one you are reading today. Yes, there are new phrases, events and figures; but the issues remain the same. And this pins us down to pointless, zero-sum controversies where the only winners are those trying to distract citizens.

The first announcer of independence is one such controversy that serves no practical purpose. In truth, the whole of Bangladesh proclaimed independence from an unfair and exploitative union: some through radios, some through songs and others through bullets. Whose voice came to provide an outlet for national sentiments is of little consequence. If a young major – at any point – conveyed a message from the leader of the struggle, it would make him a messenger. His proclamation on behalf of the leader does not make him equal or comparable to the leader. Each has his own place in history and will be remembered according to their character, integrity and deeds. Yet the controversy has haunted the nation for decades. Readers may note how the scenario presents us with two acceptable opinions, but allows lively debate within that spectrum.

Another never-ending and zero-sum debate is the question of 'Bangalee' versus 'Bangladeshi' national identities. It is difficult to write about this without being misunderstood and/or labeled as partisan, but I am nevertheless going to try. Unless qualified by what each entails, the terms in and of themselves convey no meaning. There is no value in philosophical grouping of populations, unless such categories are used to allocate state membership, protection, opportunities and resources. Still in the Bangalee-Bangladeshi debate, people toe the party line without engaging in self-reflection and critical questioning: how does this categorisation help achieve the development vision of Bangladesh? What changes if a citizen changes his opinion? Rather, all sides spar on blindly; loyally; instinctively. Such uncritical parroting of party lines, on all sides, is self-serving and no more than a reaffirmation of loyalty to political cliques.

To say that these ageing debates have no visible end in sight and add little value to domestic discourse is not to say that they should not take place, but merely that they should not be at the centre of all socio-political discourse. Binary controversies and stifling of alternative narratives are not at all unusual in countries in the process of generating national myths. In fact, the post-WWI era of nation states necessitated a process of differentiation, whereby nations had to stake out their unique mythology.

In modern Bangladesh, the tension of generating consent is heightened by the presence of broad, democratic ideals. Theoretically, the process of consolidating mono-myths is at odds with diverse stories, viewpoints and narratives ushered in by democracy. It is through the interaction of these two that nations find their identities. There is no doubt that Bangladesh is at this very critical juncture.

What is disappointing is Bangladeshis' inability to escape narrow debates with predefined positions. Let me provide an example. The Shahbag Movement of 2013 was initially heralded as the 'Bangla Spring'. The most common narrative goes that it took off with a lot of promise, but was entangled in political maneuvers soon after. While a core group survives, Shahbag's en masse urban middle-class support has waned. It is still important to note that the movement did not fail to fundamentally impact the culture, manner and language of popular protests.

The Shahbag Movement quickly lost impetus with the rekindling of an old controversy. The surge of nationalist sentiment was predictably countered with what is typically dubbed 'the Religion Card': any populist strategy that depicts a rival action (or inaction) as contrary to the dictates of religion. The 'atheist' controversy of 2013 was masterful, cunning and preyed easily on the naiveté of the God-fearing masses. Before the week ended, the electronic and digital media were abuzz with discussions about the religious orientation of bloggers (or lack thereof) and later, the murder of blogger Thaba Baba. Surreptitiously, an important conversation was subverted and channelled toward ancient binaries.

It is time to reflect on why Bangladesh still remains so mired in historic debates. Political analyst and commentator Zia Hassan in a recent post questioned why the laundering of Tk. 76,000, routine deaths from road mishaps or the lack of playgrounds for children are not issues for opposition parties – but the exact number of deaths in the Independence War of 1971 is. There are dozens more deserving issues – ranging from building safety to dying rivers and forced prostitution – that need attention and action, but are seldom covered with any enthusiasm. We need to ask ourselves, why is this so?

Historic debates are sustained through political strategy, propaganda, politicisation of civil society and failure of media to shape fresh, pragmatic agendas. A semi-literate population, cleaved along lines of historic allegiances, provides the ideal base for sustaining age-old controversies.

In layman terms, democratic action – as understood beyond mere elections – is informed by media and civil society, and carried out by citizen activists. All three, along with political rivals, act as pressure groups in order to influence policy outcomes. But what happens when these functions and relationships change? I argue that three major changes are disrupting the check and balance inherent in democracy.

The first trend is increasing self-censorship by media, stemming from the fear of backlash from beneficiaries of the current system. With the corporatisation of media, journalists and analysts have turned more risk-averse, content to ensure job-security. More importantly, over-reliance on advertising revenue compromises media's role and effectiveness as a critic of the establishment. Quite recently, two large print-electronic outlets learnt this lesson the hard way. The influence wielded by such control over media earnings gives authorities the power to shape conversations and recommend analysts and commentators (who in turn shape the agenda). The media now has less motivation to challenge existing paradigms.

The second trend is a weakening of the link between public 'opinion' and 'activism'. At the heart of this weakening, lie the degradation of 'news' and the very nature of how citizens utilise the information that they are given. Readers will appreciate that the Age of Information is also the Age of Misinformation. There are now unsubstantiated reports, unverified videos, unsubstantiated analyses and unreferenced arguments floating around on the Internet. There are satire pieces being peddled as facts. There is hate speech being advanced as rational thinking. Given the human tendency to pick up facts and arguments that support their own worldview, all political cliques are busy amassing evidence on their side without verification or critical thinking.

What is done with media information has also changed radically. As the population becomes connected via the internet, less and less people seem to be interested in physical activism. Instead, the inherent human need to protest and reform is being fulfilled by making online posts. These posts garner 'likes' and 'comments' alright – but seldom emerge out of the ether into physical reality.

Citizens' inability to translate information and analyses into political action means journalists now have little incentive to play the critic, to keep widening the range of discourse and reporting on the various issues of national development. The cost of antagonising prevailing powers remains the same, but the reward (citizen awareness and activism) has dwindled. It makes agenda shaping a less rewarding, less useful preoccupation.

Thirdly, in the age of social media, there is also a personal cost of critiquing the establishment and dominant narratives. Social incentive to conform has been very high. Broadband labelling as war-criminal sympathiser is rampant. Organised maligning campaigns against dissenters have reached Goebbelsian levels. Dissent is reward with, and only with, exclusion.

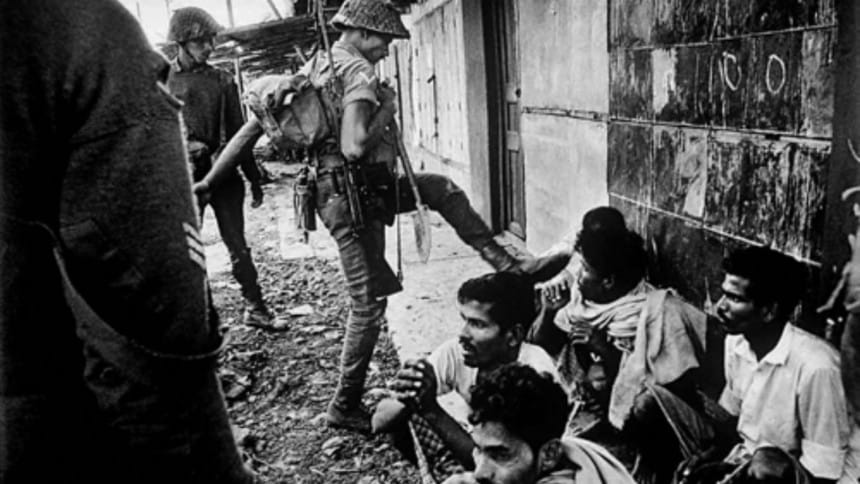

The only escape from the vicious cycle of rancid debates can come from judicious political leadership. Yet, the most prominent opposition leader has again rekindled the controversy of exact numbers from the 1971 genocide perpetrated by the Pakistan army. While no rational society should be opposed to scientific and rational inquiries into historical events, provocation for the sake of provocation is juvenile and counterproductive. The only broadening of horizons has come from an opposition stalwart who appallingly questioned the intelligence of martyred intellectuals of 1971 for endangering their own lives! While we ignore this ignominy, let us also be grateful that the martyred visionaries had the integrity, courage and fortitude to risk their very lives; let us take a minute to thank our stars that they were not like today's leaders.

The writer is a strategy & communications consultant and can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments