“I Don't Like Twirling the Baton of Politics”

BEFORE we knew it, it was the year 1970. There were political movements all around. The confrontations of the students and the public of East Bengal had reached their peak. A troubling time came then – everything seemed to be in a state of vexation. There was no tolerance anywhere, for anything. The growth of artistic sensibilities and the fine arts came to a halt. All around there were propagandas for the election; there was a sense of excessiveness, excitement regarding the election everywhere.

The Pakistani supporters suffered a terrible defeat at the elections. The supporters of independence were victorious. I wasn't able to reflect the expression of art in anybody. Gradually, the difference between night and day began to dissolve in my eyes. After overcoming every layer of time, Bangalis achieved victory in the elections. Ordinary people were overwhelmed by the happiness brought about by this triumph.

However, Yahya and Bhutto did not want the power of the state to be handed over to the Bangalis. After that, what happened was inevitable. On the dark night of March 25, 1971, the Pakistani military began to murder the Bangalis in Dhaka. Then came the sovereign Liberation War. All over the country, some people went against the liberation movement. They initiated the Shanti Bahini, the Rajakar Bahini, the Al-Badr and Al Shams Bahini. They started murdering innocent citizens. The leader of such forces in Narail was Solaiman Maulana of the village Tulorampur.

This notorious leader of the Rajakar force had murdered thousands of people. He buried alive eight to nine members of the Tarafdar family near the Wapda rest house in Rupganj. The mass grave has been conserved. Even today, this mass grave brings tears to the eyes of people. Every night Solaiman's men would slaughter people and throw their bodies in the River Chitra.

In the morning, one could see the bodies floating over the Chitra. The people of the locality were murdered. People who did not belong to the locality were also murdered. Those who were captured by the Rajakars on their way to India were taken and murdered by Solaiman's men at the launch ghat. The residents of Narail are not unaware about this. It isn't possible to make anyone realise in words what we had gone through in those terrible days and nights.

I don't want to understand any kind of politics. I don't like the twirling of political batons. I love my country, people and the earth. Am I Muslim in the eyes of religious fanatics? I am guilty of many sins. I paint pictures, but can't give life to them. I socialise with the people of the najayez (illegitimate) people of the Hindu community. I stay with them. That's why they wouldn't let me survive. The notorious rajakars of this place, Ghafur, Jabbar, Shafiraddi, Abu, Bajlu threatened to kill me. The names of the people I listed were killers; no one can say how many men and women they murdered. Looting, pillaging, raping – they didn't leave anything aside.

Disorder prevailed all around. From the people of remote villages, we learnt about their misfortune. The rajakars would plunder the houses of Hindus and set them on fire. People could see the smoke from burning houses, wounding into a ring and flying in the air. This was the scorched earth policy of the Pakistanis. But where could I go? I didn't have the scope to leave the city. I could understand that the rajakars were keeping an eye on me. I devised a plan to play them at their own game. I learnt that the Pakistani captain who was stationed at the Wapda rest house in Bhowa Khali was a Sindhi.

The Sindhi race was very different from the Panjabi race. There are more tolerant than Panjabis. One day I spoke to him. I introduced myself. I didn't forget to mention about my conversations and acquaintances with the former governor and prime minister of Sindh. I informed him about our long stay in Jamshed Road, Karachi. I explained everything to him in Urdu. Finally I informed him that the rajakars of that area had threatened to murder me. Meanwhile, the captain seemed to have melted. He accepted me as an elderly artist. For a couple of days, I travelled in the captain's car upon his request.

In the meanwhile, the captain castigated the chief of the Rajakar Shanti Bahini, Solaiman Maulana, and his men. In a way I was free. I was free of the fear and misgivings of the Rajakars. I started to wander in a free manner. At that time my movements were no longer under the surveillance of the rajakars. So one day I walked past the zamindar bari of Hatbariya and gradually reached my former workstation in Chachuri-Puruliya. I first went to Anil Sarkar's house; Anil's house was situated in the west side of Chachuri Bazaar. While in Narail-Rupganj, I had heard about the suffering of ordinary people but had never witnessed it.

Now I began to see the suffering. My heart was never ready to witness this scene. Thousands of women and men, young people were fleeing to the west in fear of their lives. The elderly were unable to walk; their family lifted them in a raised seat and were thus taking off with them. Behind them ash, burnt earth, the blood-splattered bodies of their loved ones, were all giving chase to their bloody terror. They were fleeing toward the west, past Chachuri-Puruliya, Musiya, Egarokhani. Further to the west – to the refugee camps on the land of India.

I became completely quiet. I still shiver when I think how humanity was tainted during the Liberation War of 1971. I stayed in Indu Das' and Anil Sarkar's house, and protected my life through different tricks. I even saw the infernal activities of the Pak military. Bodies over bodies, people with their eyes binded being murdered, a war carried out in protest, a mountain of dead bodies – later everything that emerged from my paint brush was all a result of my experience. I don't paint pictures from ideas taken on loan.

1971 is the bloodshed of my idea. I don't ever want to see it in a trivial light; there's no scope of seeing it in a light manner. There's no doubt that our artists effortlessly bring alive the liberation war on their canvas. However, how can that picture be complete if the artist hasn't seen or lived that reality? Many of them (the artists) haven't been able to capture the freedom fighters' anger, their grievances, their willingness to sacrifice for their country.

Freedom fighters have been shown not as a fighter but in the guise of farmer with a gamcha on his head, as he chases his cows and shelters his crops. This is the result of not seeing a freedom fighter in real life; the result of only painting from stories heard about freedom fighters instead of actually seeing them.

Yes, you are right, I haven't worked on the war. It wasn't possible for me to take part in the war. I heard and learnt about the war. How can I encapsulate it with my brush if I hadn't seen it? But I have borne the journey of the swelling protest of countless people. There is no pretension in that.

I believe that the subject of the liberation war should first be instilled in thought and intellect. The creativity of an artist can in no way be taken lightly. You have to stand in support of the conscience. Either you will stand by the truth or you'll write and paint about the dishonest path. No fraud can take place in this regard. The conscience of the liberation war is not just a picture of fights and murders. The history of free thought, philosophy and the path to human progress will be a part of the conscience of the liberation war. We aren't able to do works of such good quality. Are there any good films on the liberation war? No work has yet been done like those following the Second World War. There also haven't been good artworks painted on the liberation war. An unknown work had been done on the liberation war in Narail in 1974.

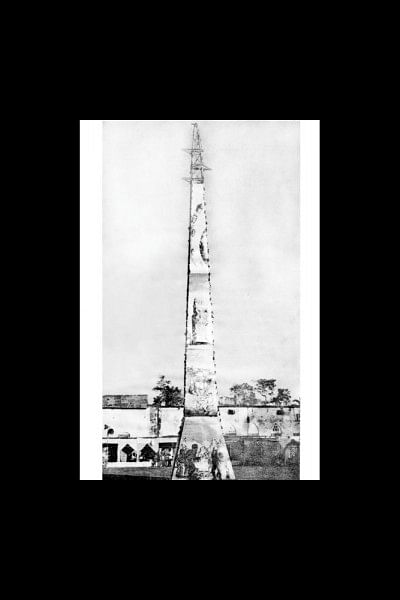

Agricultural, educational, cultural and artistic exhibitions are organised in the courtyard adjacent to the Government School in Narail. A huge tower, which is almost 90 feet in height, was built here. This tower focuses on the evolution of human beings from ancient times. I included five paintings here. The activities of the working people of ancient times found place in the lowest rank. The painting above that portrays the eternal rural people. The one above that reflects the civilisation of cities. And the one above that was a portrait of a journey into space. At the top of the tower was a huge globe which showcased the map of the whole world. This picture of the continuous evolution of civilisation carried the story of an inspired conscience, the history of human progress. It carried the tidings of freedom, of the liberation war.

Publisher: Monon Prokash

Translation: Upashana Salam

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments