“There is still hope for a Teesta deal during this visit"

The Daily Star (TDS): Delhi has made it clear that no deal on Teesta will be signed during PM Modi's visit. What will the ramifications of that be for Bangladesh?

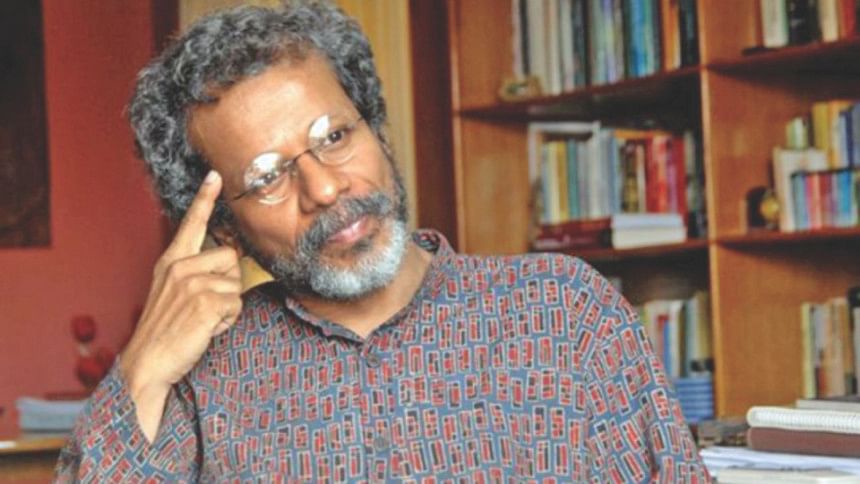

Imtiaz Ahmed (IA): I will still not rule out a deal on Teesta. Sushma Swaraj did not say that the central government is against a deal on Teesta. She basically said that Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee needs to be part of any water sharing agreement on Teesta. The issue then becomes about when and how Mamata Banerjee is brought on board.

PM Modi's visit to Bangladesh is different from that of Manmohan Singh in 2011. Congress did not have a majority then and Manmohan Singh was dependent on other parties and State ministers, including Mamata Banerjee. But PM Modi has a two-thirds majority in Lok Sabha and his government has already completed one whole year.

I don't think he will want to give off the vibe that Mamata Banerjee is more powerful than him and present that image to the international community. Since Mamata Banerjee's arrival to Bangladesh was scheduled one day prior to PM Modi's, some arrangements may have been made regarding a deal on Teesta. An alternative scenario could be that PM Sheikh Hasina will have to visit Delhi or Kolkata within a few months to continue talks on Teesta.

Since the Indian central government has already prepared a draft on Teesta, I don't see why with a two-thirds majority, PM Modi would hand over that kind of power to Mamata Banerjee. There is still hope for a Teesta deal during this visit. If there's no agreement on Teesta this time, we can conclude that there are other reasons and that this Mamata Banerjee affair is just a pretext.

TDS: The Land Boundary Agreement (LBA) is now at the implementation stage. What do you think needs to be done to implement it effectively?

IA: First we need to find the number of people who would opt to go to the other side (of the border). In a survey done in 2007 to find out the number of people willing to shift across the border, the lowest figure was 700 and the highest was 3000. I understand that the bulk of the people would be staying where they are. So in that case we need to see to it that the enclave peoples obtain all the necessary documentation like national ID and voter ID because all these years they lived in enclaves in Bangladesh that were part of India and vice versa. For these people, the LBA ratification is like Independence Day.

The government needs to be careful, especially when it comes to the middlemen employed in the provision of said documents; the civil society, NGOs, watchdogs and media need to watch out as well. Our system of governance isn't exactly the most efficient and chances of corruption are very high.

There's a misconception that the LBA will resolve the issue of cross border movements; in reality, they have nothing to do with each other. There are three things regarding the LBA: exchange of enclaves, adverse possessed land, and demarcation of undemarcated borders. Most of the enclaves are deep inside Bangladesh and India so they're not directly linked to the problem of cross border movements. The latter are mainly related to things like poverty and unequal development.

In the 70s and 80s, these movements could have been attributed to Bangladesh's lower growth rate compared to India. Post 90s, however, Bangladesh has consistently maintained a 6 percent plus growth rate which I think is good enough for people to not cross the border, largely because India's growth rate hasn't been as consistent.

Also, over the years India has built barbed-wire fences for miles after miles. That has put a stop to the flow of people across the border to a large extent because it has now become more dangerous and difficult to cross over. Looking at the recent tragic news of people attempting to go abroad by boat in order to flee poverty, it is evident that the attraction towards India is waning in comparison to Indonesia, Malaysia and other countries.

TDS: How can we reduce the historic trade gap that we have with India?

IA: Firstly, in an age of globalisation, analysing a one-to-one relationship in the context of supply and demand and only looking at the trade surplus or deficit with one country isn't the right way of looking into things. You have to take into account factors such as raw materials being brought in from different parts of the world, value added to the product, cheap labour, etc. After all these processes take place, the final product is exported. From that point of view, I don't see the trade deficit with India to be as problematic. We also have a trade deficit with China.

Consider our RMG sector. 20% of the cotton comes from India, the bulk of it comes from Central Asia; machines used to come from Germany, now they come from China; designs come from New York or Milan; the products get value added in Bangladesh after which they're exported. Bangladesh has a trade surplus with the EU and the US, and a growth rate of 6% overall. We have to look at all these interactions instead of focusing on a one-to-one relationship.

Secondly, the quickest way to reduce trade deficit with India would be to focus on production on the basis of partnership. For instance, it may be cheaper to produce a certain item in Comilla or Sylhet rather than sending goods from West Bengal to Tripura or Assam. It would benefit our workers and would be a win-win situation for Bangladesh and India.

TDS: Bangladesh is situated between two giants: India and China. What are some ways in which we can exploit the opportunities as a result of our blessed geopolitical position?

IA: The easiest way would be to create a robust production sector. China has showed us the way and is a great example. China is one of the largest trading partners of the US. China achieved this feat not with rail and road connectivity with the US but with a globally competitive production sector.

Our RMG sector is the second-largest RMG hub after China. It is not roads or railways that sprouted the growth of our garments industry. It all started with production houses, and road linkages and other forms of connectivity came later. This isn't a chicken-and-egg situation. You have to have the 'honey' which is the production sector, and one of the reasons why it's possible to have a large production sector in this part of the region is low labour costs which, in turn, help make items produced here competitive in the market. In the age of globalisation, it is possible for India, China and Bangladesh to join hands, form partnerships and build production houses to facilitate the movement of goods to different parts of the world. If we build a strong production sector, all this connectivity we speak of will follow eventually.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments