Is everyone celebrating?

The euphoria, both inside the country and outside, which followed the recent and historic elections in Myanmar, was only to be expected. One hopes, at the same time, that it was not premature. History is awash with instances where populist and charismatic leaders turned out to be inept administrators and ended up becoming autocratic dictators. Hopefully, Aung San Suu Kyi will be among the exceptions.

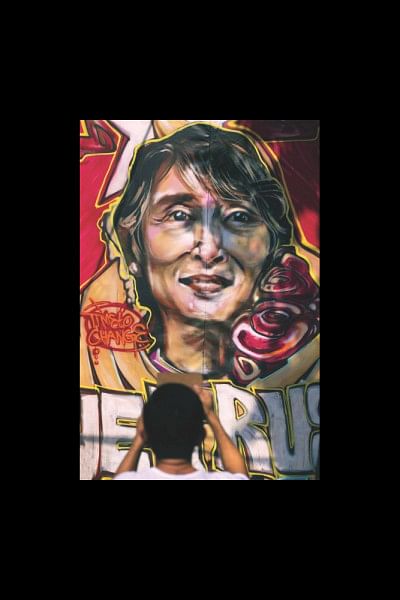

Riding a wave of unmatched popularity and cashing on her personal charisma, Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi led her National League for Democracy (NLD) to an unprecedented landslide victory at the polls held on November 8. After more than two decades of defiance in the face of repressive authoritarianism, Suu Kyi's resilience stands vindicated. Her perseverance has been duly rewarded. The military backed party USDP has conceded defeat.

Suu Kyi, the daughter of the country's independence hero General Aung San, headed a non-violent opposition to Myanmar's military rulers since the aborted 1990 election, a great part of which she was forced to spend in isolation and under house arrest. No amount of repression, however, dampened her indomitable spirit. She even spurned offers of freedom from imprisonment by the military rulers if she agreed to leave the country for good. The decision meant not seeing her British husband before his death from cancer in 1999 or watching her two sons grow up.

As the dust of her resounding victory settles, Suu Kyi and her colleagues will have to take stock of certain sobering realities that lie ahead before her party takes office in March next year, assuming of course, all else remains same till then.

The ruling junta has accepted the outcome of the election, with the caveat that Myanmar must have a 'disciplined democracy', the implication of which is open to interpretation. The country's constitution crafted by the military rulers stipulates 25 percent seats in the parliament for the military. These seats will not be elected but appointed. Besides, the constitution also ensures that the key ministries of Defence, Home and Border Affairs will be headed by the military. These arrangements mean that even with such a strong mandate, the NLD will not be allowed complete sway over decision or policy making.

Then there is the big question of who will become the country's president, which is the office of the chief Executive. The current constitutional provisions bar Suu Kyi from assuming that exalted office as her sons have foreign citizenship. The military is unwilling to change that. Besides, one of the two vice presidents will come from the military, thereby putting checks on whoever becomes the president. Suu Kyi, however, surprised observers by announcing that she will be 'above the president', a call not seen as being in line with conventional democratic norms and practices.

Hence managing the transition without giving cause for worry to the military will be a major challenge for Aung San Suu Kyi and her party. As things stand presently, the NLD may be left with little choice than to settle for sharing some power with the country's military and the people of Myanmar may end up living with "controlled democracy", which is perhaps better than no democracy.

Internationally, Suu Kyi will also need to address the lukewarm response to the election outcome from China, Myanmar's most important and strategic neighbour. Beijing, which has for decades been close to Myanmar's successive authoritarian military leaders, has so far stopped short of congratulating Suu Kyi or the NLD and has only provided assurances of assistance, friendship and "mutually beneficial cooperation". China had taken a pragmatic stance on the evolving political developments in Myanmar and the Communist Party invited Suu Kyi to Beijing in June this year, a recognition that the party she leads would most likely come to power. While in Beijing, Suu Kyi met President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People, a symbolic gesture usually reserved for visiting heads of governments or states. Beijing will now wait to see how far this crucial relationship evolves as per script, Beijing's script.

Among all the jubilations following the election outcome, one group that is holding back on celebrating just yet is the Rohingya Muslim population living in the Rakhine state. Stripped off their right to vote by successive military governments, this ethnic and religious minority group had no role to play in this historic election and was reduced to being silent spectators. The country's Election Commission even disqualified every single Muslim candidate.

For long the Rohingyas have been a persecuted and a discriminated lot. This group continues to suffer from scorn and open hatred by Myanmar's Buddhist majority, especially the powerful Buddhist clergy. More than a hundred and forty thousand of them are passing their days in utter misery in refugee camps after being internally displaced following the violent Buddhist-Muslim riots of 2012. Their treatment has drawn international criticism and censure. Even Suu Kyi, feted by many in the West as a champion for democracy, has been criticised abroad for her disturbing silence on the fate of the Rohingya Muslims. As the Election day drew close, she was even quoted as saying the issue is "being exaggerated" by the critics, clearly opting for a 'pragmatic' approach meant to pacify the Buddhist majority. In so doing, she risked raising further fear among the Rohingyas and the international community alike. Dealing with this issue, therefore, will be one of the most controversial, and unavoidable, in a long list of issues Suu Kyi will inherit from the military government. An NLD led government will in all likelihood come under increased international pressure to take a definitive stance on this sensitive yet critical issue.

However, Suu Kyi is also aware that speaking out for the Rohingya would carry a political cost at home, both among the Buddhist majority and the powerful military establishment, and even among some in the NLD. The hardliners see the Rohingyas as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. She could see a haemorrhaging of support by taking up the cause of the beleaguered minority too openly.

The NLD also faces a powerful local rival in the Arakan National Party (ANP) that has been accused of stoking anti Muslim sentiments and has even called for the deportation of the Rohingyas. The ANP won most of the 29 national level seats in Rakhine and has a decisive control of the state's regional assembly. How she will balance the diverse positions will be a real test of her political acumen. There is also a bigger angle to this issue. Scorned and fleeing persecution at home, exiled Rohingya refugees, especially the youth, have become easy recruits for extremist groups like the Al-Qaeda and now the IS.

So far the NLD has offered little in the way of clear policy to tackle the Rohingya citizenship status or their resettlement and integration in the society. The only ray of hope, albeit a guarded one, came from comments by the Party's senior leader Win Htien that the 1982 Citizenship Act that denied the Rohingya full citizenship "must be reviewed because it is too extreme". What that will mean in concrete terms once the NLD assumes office is something one will have to wait and see.

Till then, the Rohingyas may continue to hold back on celebrating Aung San Suu Kyi's thumping victory.

The writer is a former Foreign Secretary and Bangladesh High Commissioner/Ambassador to Sri Lanka, Germany, Vietnam and the United States.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments