Letter from QANATAR

When I received my marching orders for Egypt, I knew it was meant to be a punishment posting. Based on unsubstantiated allegations of supporting her opponent, the then Prime Minister had decided my fate; I was to go to oblivion. To me, a posting to Egypt was a gift. I had long cherished the desire to see the country of the pharaohs, walk the streets of old Cairo, browse around Khane Khalili bazaar, sip coffee in the coffee shops frequented by the great Egyptian Nobel laureate Nagib Mahfouz and visit the famed Al Azhar University where my uncle studied in the 1930s. But my mission to Egypt became much more challenging and meaningful when browsing through old files in the process of cleaning up. I found an English translation of a letter written in Arabic by my Egyptian staff seeking permission to visit two Bangladeshi prisoners long interned at the Qanatar prison. I was told that an Egyptian staff member visited these two prisoners twice a year to verify if they were still serving their life term for smuggling drugs into Egypt, an offence for which there is no mercy. While visiting, he would buy some local food for the prisoners and check on their welfare. The two Bangladeshis, one a cook and the other a sailor, were working on a foreign vessel when the Suez Canal police inspected it. The police claimed to find drugs in their luggage. Both denied the charges but under Egyptian law and the language barrier, there was no respite for them. By the time I presented my credentials to President Hosni Mubarak in 2006, the two Bangladeshis had served nearly 18 years behind bars. Egyptian prisons are in the middle of deserts, far away from civilisation. Prisoners serving life terms had little hope of returning home and seeing their loved ones again. The twice-yearly visits from the Embassy were therefore greatly cherished as this was the closest to being in touch with Bangladesh.

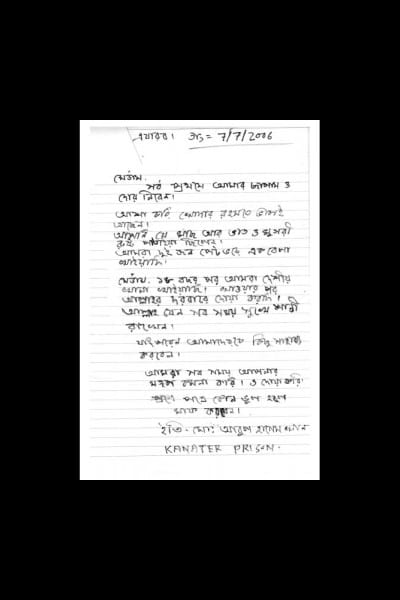

I had found my mission in Cairo. Instead of sending the Egyptian staff who did not speak a word of Bangla, I sent my First Secretary to visit the prisoners. Apparently, this was the first time that a Bangladeshi had visited them at Qanatar. He took with him home cooked food prepared by our excellent cook Ramiz. Soon thereafter, I was pleasantly surprised to receive a letter dated July 7, 2006 from the Qanatar prison which read "Madam, Please accept my salaam and doa. Hope by the grace of God you are keeping well. With the fish, rice and chicken roast that you sent the two of us had one huge meal that filled our stomach. Madam, after 18 years we ate deshi food. After our meal we prayed to Allah so that he may keep you happy and peaceful at all times. If you can, please help us. We wish you well and we are always praying for you.…………… Sincerely, Md. Abul Hashem Khan, Kanater Prison".

I needed to get them freed.

While petitioning for pardon with the high and mighty in the Egyptian government of Hosni Mubarak, I was repeatedly reminded that the presidential pardon was not applicable to drug smugglers. From Embassy staff to friends in the diplomatic community who had sailors languishing in Egyptian prisons on similar charges, everyone warned me that it was an impossible mission. I refused to accept that argument and tried to get their names on the yearly presidential pardon list, until it was time for me to leave Egypt.

As I was about to leave the country, the president's Chief of Staff Mr. Suleiman Awad called to say adieu and let me know that there was hope that my prisoners could be considered for pardon soon. In November 2007, I returned to Dhaka with great sadness as the prisoners could not return home despite my best efforts. Next year, in January 2008 Counsellor Shahidul Karim informed me from Egypt that the two Bangladeshis were pardoned and released.

The cook having received his freedom from prison was imprisoned by his heart. On receiving news of his pardon, Hashem died of a massive heart attack and was later buried in Egypt. His shipmate came back to his family after living under the sands of an Egyptian desert for more than 18 years.

The letter from Qanatar remains my priceless memento from Egypt.

The writer is a former ambassador.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments