A Massacre in Africa

WHY is it that schools and schoolchildren have become such high-profile targets for murderous Islamist militants? The 147 students killed in an attack by the extremist group Al-Shabab at a college close to Kenya's border with Somalia are only the latest victims in a succession of outrages in which educational institutions have been singled out for attack.

Last December, in Peshawar, Pakistan, seven Taliban gunmen strode from classroom to classroom in the Army Pubic School, executing 145 children and teachers. More recently, as more than 80 pupils in South Sudan were taking their annual exams, fighters invaded their school and kidnapped them at gunpoint. Their fate has been to join the estimated 12,000 students conscripted into children's militias in the country's escalating civil war.

Every day, another once-vibrant Syrian school is bombed or militarized, with two million children now in refugee camps or exiled to makeshift tents or huts. And next week will mark the first anniversary of the extremist group Boko Haram's night-time abduction of 276 schoolgirls from their dormitories in Chibok, in Nigeria's northern Borno state. With continued assaults on local schools, Boko Haram has escalated its war against education – making the last two years Nigeria's worst in terms of the violation of children's rights.

In the past five years, there have been nearly 10,000 attacks on schools and educational establishments. Why is it that schools, which should be recognized as safe havens, have become instruments of war, and schoolchildren have become pawns in extremists' strategies? And why have such attacks been treated so casually – the February abduction in South Sudan elicited barely any international comment – when they in fact constitute crimes against humanity.

In the depraved minds of terrorists, each attack has its own simple logic; the latest shootings, for example, are revenge by Al-Shabab for Kenya's intervention in Somalia's civil war. But all of the recent attacks share a new tactic – to create shock by exceeding what even many of the most hardened terrorists had previously considered beyond the pale. They have become eager to stoke publicity from the public outrage at their methods, even transmitting images of their crimes around the world.

But there is an even more powerful explanation for this spate of attacks on children. A now-common extremist claim is that education is acculturating African and Asian children to Western ways of thinking (Boko Haram in the local Hausa dialect means "Western education is a sin"). Moreover, extremists like Boko Haram and Al-Shabab calculate that they can attack schools with impunity.

Hospitals tend to be more secure, because the Geneva Conventions give them special protection as safe havens – a fact often recognized by even the most murderous of terrorist groups. Until recently, we have done far too little to protect schools and prevent their militarization during times of conflict. But, just as wars should never be waged by targeting hospitals, so combatants should never violate schools.

Once slow to respond, the world is now acting. Thirty countries have recently signed up to the Lucens or Safe School guidelines, which instruct their military authorities how to prevent schools from being used as instruments of war. Leila Zerrougui, Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, recommends designating abductions of children from schools a "trigger violation" for the naming of terrorist organizations in the secretary-general's annual report to the Security Council.

And, thanks to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, the Global Business Coalition for Education, and former Nigerian Finance Minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Nigeria has now piloted the concept of safe schools. This has meant funding school guards, fortifications, and surveillance equipment to reassure parents and pupils that everything possible is being done to ensure their school is safe to attend. Now, under Prime Minister Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, Pakistan is adopting the safe school plan.

In a year when there are more local conflicts than ever – and in which children have become among the first (and forgotten) casualties – it is urgent that we make stopping attacks on schools a high priority. In dark times, children and parents continue to view their schools as sanctuaries, as places of normality and safety. When law and order break down, people need not only material help – food, shelter, and health care – but also hope. There is no more powerful way to uphold the vision of a future free from conflict than by keeping schools running.

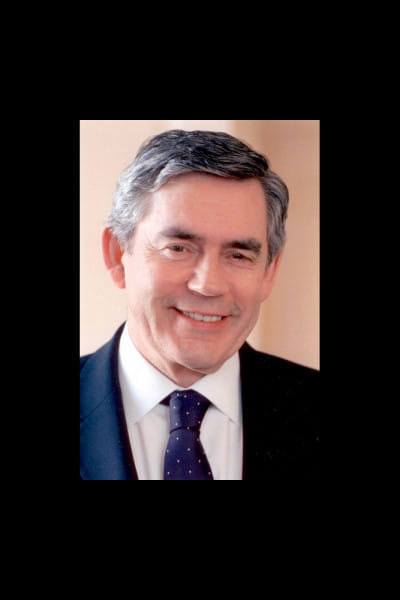

The writer is former Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer of the United Kingdom, is United Nations Special Envoy for Global Education.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments