A model, not a test case

In 1976, a book titled "Bangladesh: The Test Case of Development" drew significant attention and the hopeless implications of the title got stuck ever since; most likely, in response to Henry Kissinger's infamous reference to Bangladesh as a "bottomless basket". The book was titled not as "a" but "the" test case for development.

In other words, if "development" would work in Bangladesh, it would work everywhere.

In the 1970s "development" meant foreign capital, foreign aid and foreign know-how. At that time, many feared Bangladesh would not survive as an independent nation. One famine, at least five military coups, four catastrophic floods, and several disastrous cyclones later, where is Bangladesh now?

It has not only survived, but prospered despite the hopeless predictions of 1970s. How did this happen? What makes Bangladesh no longer a test case – but a model – for development, ingenuity and resilience?

A MODEL FOR DEVELOPMENT

In the last 40 years, Bangladesh has made extraordinary improvements in almost every indicator of social development. It met almost all the Millienium Development Goals. The country has made remarkable progress in poverty alleviation, primary school enrolment, gender parity in primary and secondary level education, lowering the infant and under-five mortality rate and maternal mortality ratio, improving immunisation coverage and reducing the incidence of communicable diseases.

A Bangladeshi can now expect to live four years longer than an Indian, though Indians are twice as wealthy. It has made huge gains in education and health. In 2005, more than 90 percent of girls were enrolled in primary school, which was twice the female enrolment rate in 2000. Infant mortality has more than halved from 1990 to 2010.

A MODEL FOR INGENUITY

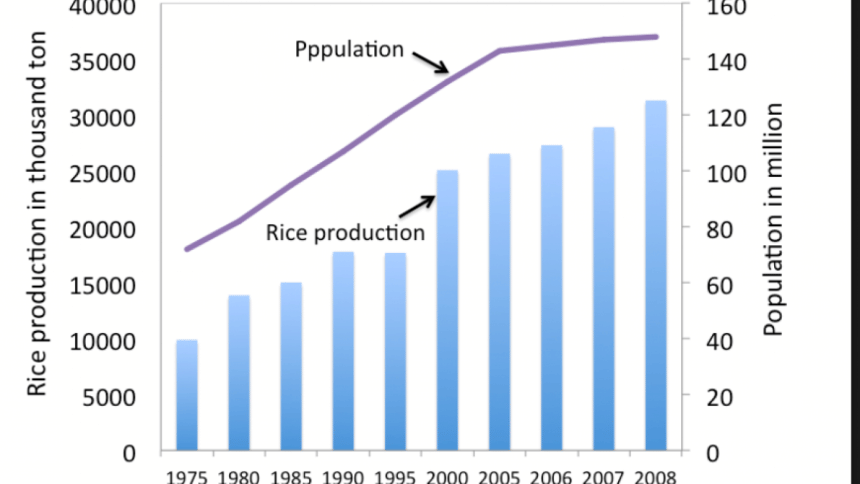

Unlike China's one-child policy or India's forced sterilisation in 1970s, Bangladesh adopted a culturally sensitive and ingenious approach to tackle population growth. Birth control was made free and government and non-governmental workers fanned out across the country to distribute pills and advice. While in 1975 only 8 percent of women were using contraception, by 2010 the number was over 60 percent. Bangladesh has shown one of the steepest declines in fertility rate (the average number of children a woman can expect to have during her lifetime) of 6.3 in 1975 to about 2.2 which is slightly above the "replacement level" at which the population stabilizes in the long term.

Between 1970 and 2010, Bangladesh has more than tripled its rice production - by creatively supplementing traditional rain-fed aman rice with irrigated boro-rice in the winter - although the area under cultivation increased by less than 10 percent. Despite several global food-price spikes, many disastrous cyclones and floods, it has not experienced famine since 1976 and exported 50,000 Metric Tons of rice to Sri Lanka in 2014.

Due to increased urbanisation most developing countries have seen a reduction in rural living standards and a resultant increase in extreme poverty. Bangladesh is an exception here. Ingenious Bangladeshi villagers found actionable solutions within the constraints they have. Homogeneity of language, culture, and religion has proven helpful for NGOs to scale up development efforts. What worked in one village is likely to work in the next village and the next village is not far away. Another contributor to development in rural Bangladesh is the massive migration of over six million Bangladeshis – mostly male – to foreign countries. They send a large portion of their income to their families and relatives in villages. In 2014, they sent over $14 billion. By some calculations, remittances exceed net aid by a factor of 20: a remarkable success for the "bottomless basket" of 1970s. Yet, whether this glowing success indicator is contributing to an apparently hidden – but potentially problematic – social change related to "absent groom" and "runaway bride" in villages remains to be seen.

A MODEL FOR RESILIENCE

The cyclone of 1970 was estimated to have killed over half a million people in Bangladesh while the 2007 cyclone Sidr was more powerful, but killed only one hundredth as many. This pragmatic response to natural disaster shows how effectively Bangladesh has learned and adapted through careful planning and effective implementation of cyclone shelters and early warning systems.

In 1970s, in many developing countries, diarrhea was one of the leading causes of childhood mortality. Many solutions were possible to combat this global problem. Several national and international governmental and non-governmental organisations started working together and developed an extraordinary actionable solution - oral rehydration therapy (ORT) - consisting of sugar, salt, and water to save lives of millions. The development of ORT is considered by many as a magic bullet that has saved more lives than any other medical discovery of our time. The simplicity of ORT and BRAC's implementation strategy to popularise and spread its use made a significant drop in diarrhea related mortality actionable.

BANGLADESH'S MODEL IS NOT AN ORPHAN

Not surprisingly, different groups will fight over who and what is responsible for the successes of Bangladesh. Key contenders include the government, politicians, army, international community, and the NGOs. Success usually has many parents and an independent 'paternity test' for this remarkable story would be difficult and may not be necessary or even helpful. Despite dysfunctional institutions, level of poverty, and widespread corruption, Bangladesh has achieved progress in many social development indicators by creating social awareness and implementing context specific actionable solutions. Many are somewhat surprised by this success and rightfully skeptical about its sustainability because of fragile governance structure, inadequate long-term planning, and uncertainty imposed by changing climate and sea-level rise.

Now, instead of looking for the parent for this story of success or surprise, we should ask: What made this success possible? What will it take to make this sustainable? How to tell this story and engage the world to promote Bangladeshi Brand of Ingenuity and spread this recipe for success to other developing nations?

Please share possible to actionable ideas to [email protected] that we can discuss and create a network of partners to address these societal problems in actionable ways.

The writer is Director of Water Diplomacy, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Professor of Water Diplomacy at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, USA. Twitter: @ShafikIslam

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments