A PERSONAL FOOTNOTE

A year ago today, the world celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. A small part of that history is my personal history, as a senior official of the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, and that of a small group of East German refugees in Hungary seeking safe passage to West Germany. As the world grapples with the present stream of refugees on the same continent, this story is timeless.

Our story begins in June 1989, when 169 East German youths and their families entered neighbouring Hungary. They overran the West German Embassy in Budapest, threatening not to leave the premises till they were recognised as refugees and allowed safe passage to West Germany via Austria. Working in the Protection (Legal) Division of UNHCR at the time, it was my task to go to Budapest to ensure their protection and negotiate an arrangement for their passage to West Germany, which had agreed to receive them.

Let us recall the tumultuous developments that were taking place in Europe in 1989. Agitations against the Soviet Union and revolt against authoritarian regimes in the Eastern Bloc rose throughout the 1980s. By 1989, they culminated in regime changes and democratic reforms in Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. In East Germany, too, protests intensified in 1989. There was widespread and seething anger against the regime. Protestors demanded democratic reform and, in particular, removal of restrictionson freedom of movement. The Berlin Wall, the physical manifestation of the Iron Curtain, was seen by the people as a symbol of division between East and West of Europe as well as between East and West Germany. It was also the period when the Cold War was about to reach an end with a reform-minded Soviet Leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, at the helm of affairs in Moscow.

When I arrived in Budapest in June 1989, I was welcomed to the hotel by the West German Ambassador, who had set up his office there, having been dislodged by the asylum seekers. For the next few days of my stay there we remained constantly in touch. It seemed to me that he was also regularly in touch with his capital, Bonn. He made me feel that the latter wanted to make sure that I did not leave Budapest till I obtained the permission for the asylum seekers to leave for West Germany. I had an eerie feeling that the asylum seekers were part of a larger plan.Whenever I went to see them at the West German Embassy, I was struck by their youthful exuberance and ever joyous, confident and friendly demeanour. I hardly noticed any worries among them, which is normally not the case with most refugees.

In my meetings with the Hungarian foreign office, I was given full assurance that the asylum seekers would be treated as refugees and the Hungarian authorities were fully aware about their responsibilities under the 1951 Refugee Convention. They also reminded me of their meetings with me and my colleagues in Geneva barely six months ago, which culminated in Hungary's accession to the Convention. I still vividly remember the joy we all felt when Hungary announced its decision to become the first Soviet Bloc country to do so.

Little did we realise at the time that there was a specific purpose behind Hungary's accession. Through my talks with Hungarian officials, I came to understand why Hungary wanted to assume international obligation to protect refugees on its territory in the first place. It is because they wanted to use their refugee protection responsibilities, if needed, to counter the obligation imposed upon them by their membership of the Warsaw Pact. An ostensible purpose of the Warsaw Pact was to control movements of citizens from member countries to non-Warsaw Pact countries without permission from national authorities.

My talks with the Hungarian authorities convinced me that the East German refugees were well protected in Hungary and I need not worry about them. Although I was then ready to return to Geneva, my boss, the High Commissioner for Refugees, Mr. Jean Pierre Hocke, insisted that I should leave Hungary only with the refugees. I realised that the High Commissioner was under pressure from the West German Government.

When the authorities learnt about my decision not to leave Budapest soon, I was called in by the Foreign Minister for a chiding. He told me about his disappointment that UNHCR did not seem to fully understand contemporary political developments in Eastern Europe and the imminent changes they forebode. He then explained why the Hungarian Government could not let the refugees go to West Germany immediately as it was waiting for a green signal from the Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, in this regard. The latter apparently was assessing the likely reaction of the Soviet Red Army should the borders be opened by Hungary and an uncontrollable pandemonium ensued. He recalled in this regard the experience of Hungary in 1956 when the Red Army overran Budapest with battle tanks to crush a popular uprising for change and reform.

The Foreign Minister, however, assured me that as soon as his Government received the green signal from Mr. Gorbachev, the barbed-wires on the borders to Austria would be cut and refugees would be able to leave through it. I was invited to come back then if I wished. He requested, however, that in the meantime UNHCR should refrain from talking about it. I understood the reason. As a passing remark he asked me to ponder on the likely fate of the Berlin Wall once the Hungarian borders are opened to East German citizens to go anywhere and they begin to use it.

When I came back to Geneva the next day, the first thing I told my family, friends and colleagues was that the Berlin wall was going to fall soon. This was still June 1989. They of course laughed at me and my daughter reminded me of the nursery rhyme I used to read to her in which Chicken-Licken ran around telling everybody that the sky was going to fall down. Next day the High Commissioner got a call from the West German Foreign Minister, Hans Dietrich Genscher, who complained about my return without the refugees. The High Commissioner was well-briefed for the response.

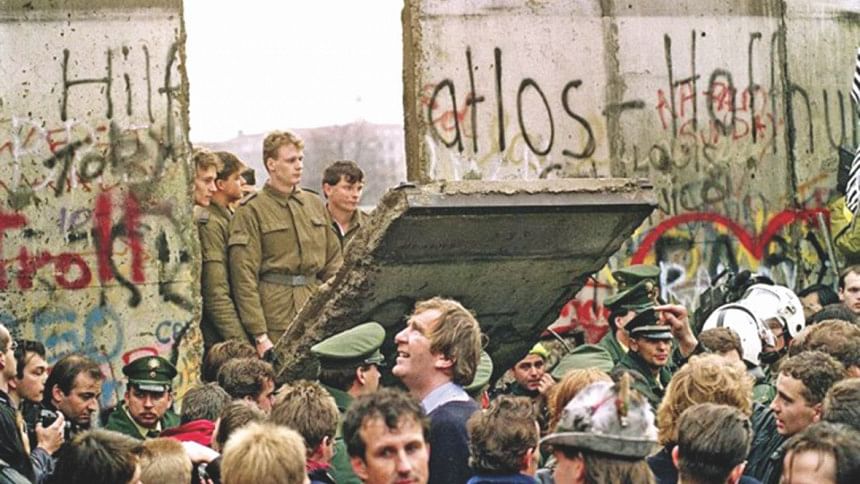

Hungary opened its borders with Austria in August 1989, in tandem with Czechoslovakia, and the rush of East German citizens to leave the country became inexorable. The Government of strongman Honecker fell under intense pressure in October and the new East German Government was forced to consider allowing citizens to travel to the West officially. However, before a decision was finalised, a Government spokesman, Gunter Schabowski, mistakenly announced to the press on November 9, 1989 that East Germans were now free to travel to foreign countries.

The announcement had an electrified effect, the main thrust of which fell upon the Berlin Wall as people began to chip it away to end close to thirty years of its existence. The rest is history and the dawn of a new unified Europe.

Mr. Gunter Schabowski whose historical mistake triggered the final assault on the Berlin Wall passed away on November 1, 2015. He was eulogised by many for his role. We must not, however, forget the role played by the refugees in Budapest and the well-orchestrated role that the Hungarian Government and President Gorbachev played in bringing the developments to a logical, non-violent conclusion.

As historians delve into this period of history, they should analyse the decision of the Hungarian Government to accede to the 1951 Refugee Convention not only in the context of developments in 1989 but also in relation to the large influx of Syrian and Iraqi refugees into Hungary in more recent times and the demand made by the world on Hungary to provide them protection under the Convention. Would the situation have been different if Hungary had not acceded to the Convention then? History is created in such unpredictable ways!

The writer is the Chairman of Research Initiatives, Bangladesh (RIB) and a former Director of UNHCR.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments