Pondering the imponderable

A few days ago, in a news interview in Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) radio here in the US, a journalist covering events in Afghanistan provided a grim view of the prospects of democracy in that country. He doubted if Afghanistan could have a democratic government any time soon, and added that the people of Afghanistan would be lucky if the country could rise to the level of even Bangladesh in one generation. That was a compliment to Bangladesh I thought, however left-handed it might have been. At least there are people in the outside world who thought of Bangladesh as a democratic country. I wondered if the journalist was aware of what was going on now in Bangladesh in the name of democracy and democratic practices. But he was a savvy journalist, and I am sure he knew full well what was going on in Bangladesh.

That an international journalist considered Bangladesh a democratic country is not an endorsement of the current politics of violence in the country; it is a recognition of what the country achieved over last four decades to establish a tradition of democracy, however flawed it may be. It has not been always an easy ride, since the country that was founded on ideals of democracy and secularism had its constitutional ideals badly mangled within four years of its birth.

It would take another two decades to reestablish democracy, but not before long periods of movements led by the same set of political leadership that paradoxically is bringing the country to its knees now. It is an irony that the leaders who fought shoulder-to-shoulder against an authoritarian regime and brought back the rights of the people would be engaged in politics of confrontation and apparently a battle for personal power.

This need not have happened if the major players of today's politics actually had the interests of the country in their heart. This would not have happened if the parties in today's politics of confrontation respected the wishes of the people they claim they are fighting for. Because what is really at stake is not their own political future, but the future of the country.

It took us more than forty years to come to where we are now. Our institutions may not be very efficient, but we built these institutions through hard work of our people who were led by one goal, that of building a new country that was born out of struggle and sacrifice of millions. Made in Bangladesh is a label displayed in products that are marketed globally and is a matter of pride to Bangladeshis at home and abroad, as are the Bangladeshis who have earned a name for their country serving all over the globe.

The accomplishments of forty plus years did not happen in a vacuum, nor would these have happened if the country were a rudderless ship. Our politics may not have given us a statesman of vision, but despite the vagary of politics we got leaders who took their own initiatives to build the country of their dream. They built institutions and teams who would give leadership in education, rural development, health, and employment generation. Entrepreneurs built a large manufacturing sector employing hundreds of thousands of females, and filled in growing global demands for quality and cost-effective products.

The labour sector boomed, exporting labour to countries that appreciated the quality and hard work of our people. The biggest irony, however, is that when the country was developing economically strong, politically it witnessed a downward spiral beginning the day democracy was restored. Politics of cooperation yielded place to politics of confrontation.

A new dawn ushered the country into an uncertain time and a more uncertain future. Normal politics became abnormal, and the abnormal became the new normal. From this point, the country entered into a new paradigm of struggle for political power, in which street would replace the parliament, political debate would be replaced by armed violence and terrorism, speech would be replaced by bombs and explosives, and political campaigns by murder and arson. Vengeance, intransigence and intimidation became the new characteristics of politics. Each of the two major parties that ran government in last twenty years (except for 2006-2008) faced boycott or violent opposition in their tenure with shutdown and strikes that would paralyse the country for days and cause the economy to founder.

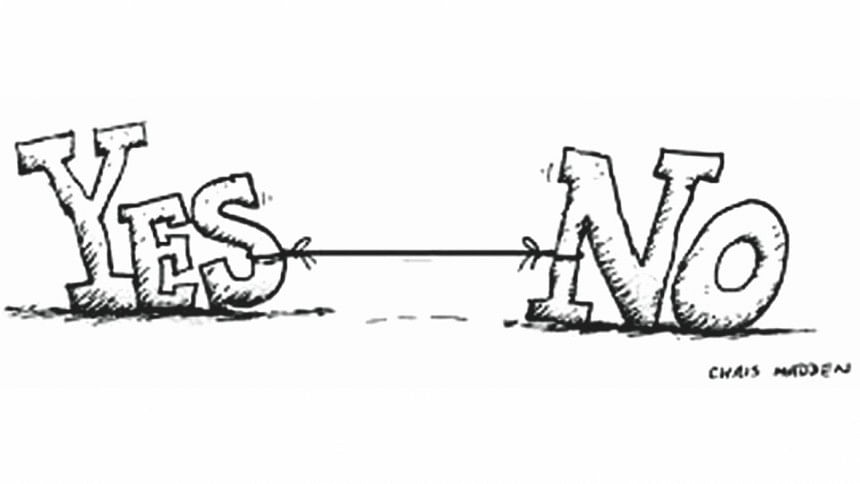

Confrontation between political parties is expected, but within the parameters of law and institutional structure. Such confrontation would normally happen in election campaigns, wooing of voters, and in the parliament. But in our case this confrontation has only one meaning, violence and terrorism. The government bears down on opposition with repression and excessive force, and the opposition responds with greater violence. What the two parties refuse to admit is that, in this politics of confrontation, the people are their hostage and future of the country is at stake. By refusing to open a dialogue to end this confrontation they are only taking the country to a precipice of grave danger. Politics of confrontation and vengeance is not what Bangladesh was founded for, nor was it founded to benefit a coterie of political groups. Will sanity return to our leaders so they end this cycle of violence and terrorism?

The writer is a political analyst and commentator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments