Rationality of fuel prices

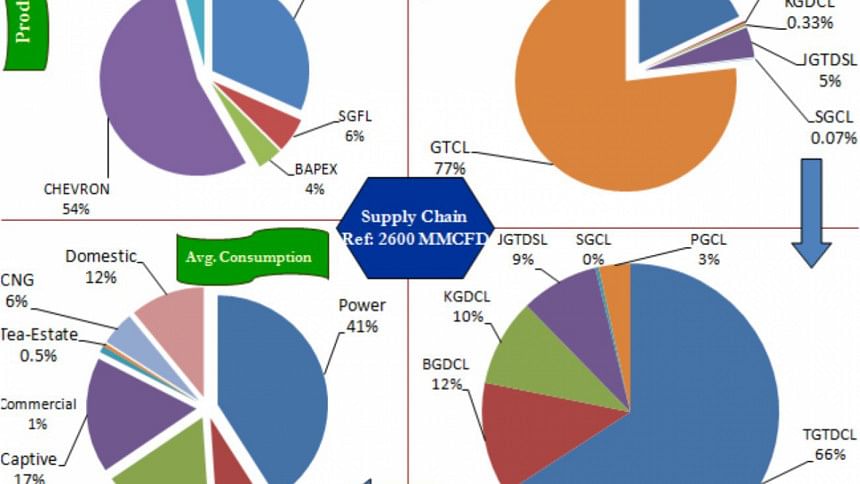

It is now generally agreed by all major stakeholders that gas reserves in the country are finite and depleting. In the absence of significant new gas field discovery over the last few years, we are now stuck with a proven and probable gas reserve of around 14 trillion cubic feet (tcf). With our current consumption of about 1tcf per annum, current gas reserves should last a little more than a decade, since gas production will start to dip as wells near the end of their shelf life. Yet, we continue to waste this precious resource with unrealistic pricing. The discrepancy in pricing between one unit of compressed natural gas (CNG) and per litre of octane is so vast that it has fuelled the massive conversion of vehicles that is eating away increasingly at our daily production of gas. Experts have stated that current CNG consumption stands at around 6 percent of our daily natural gas production.

The government has been toying with the idea of introducing liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) as an alternative to CNG. While this makes sense, the reality is that the introduction of LPG for large scale consumption at consumer level is still some years away as associate infrastructure will have to be built starting from terminals to LPG stations and actual conversion of vehicles. All this requires finance and time. So, what are we to do in the meantime? Letting things stand as they are is not really an option. Cheap gas is not so cheap anymore given that there are far more pressing needs for gas than powering sedans and luxury vehicles. For instance, the Chittagong industrial belt has not been able to expand for many years as there is no new gas connection for new industries or even established industries that wish to expand. The chronic shortfall of around 500 mmscfd (million million standard cubic feet per day) of gas has not been addressed as there is simply no extra gas available.

Introduction of CNG for private vehicles was done on the premise that at the time Dhaka was suffering from massive air pollution. Price per cubic feet (cft) of gas was kept at a throwaway Tk 8 per cft. Over a very short period, vehicles of all sizes and capacities ranging from cars to 4-wheelers and more alarmingly, city buses had converted to this very cheap fuel. Over the last eight years, price of CNG has moved from Tk.8/cft to the present rate of Tk30/cft. Ironically, global oil prices per barrel have flattened out at around US$40-45 in the international market over the last one year. But we find that Bangladesh Petroleum Corporation (BPC) is making bumper profits by selling Octane at the same Tk 99 per litre. BPC arguments notwithstanding, with petrol costing three times as much as CNG, there is zero possibility of stopping the mass conversion of new vehicles hitting the roads and CNG consumption of the overall daily production of gas will continue to mark a steady growth.

We are informed by the finance minister that the government is mulling a cut in fuel prices within a fortnight. This is very good news indeed. The question of course is: precisely how deep a cut is the government considering? According to what has been presented by one energy expert at a recent seminar 'Energy Challenges 2030' organised on August 23, BPC will still make profit if octane is sold at Tk 50 per litre. To what extent prices will be reduced is a decision for the government, but consider this. Would it not be more rational if prices of per unit of CNG were raised and price per litre of octane/petrol reduced to meet halfway? For instance, a price differential of Tk 10 between CNG and petrol/octane would have far greater impact at retail level than simply slashing prices of octane.

It would discourage conversion or even usage of CNG because the average vehicle must wait for hours every day to refuel at CNG pumps. There is also the question of wear-and-tear since CNG conversion reduces engine life significantly on petrol-driven vehicles. And it is not only the engine that gets a shorter lifespan; a 45+ kg cylinder stuck in the boot of a vehicle plays havoc with its suspension, leading to faster than usual replacement of many parts. Vehicle owners would take all that into consideration if CNG was no longer a cheap alternative to liquid fuel like octane and petrol. Most owners would opt to go for a petrol refill instead of wasting several hours a day waiting in line to top up. And CNG-driven vehicles would ration their travel which would also have positive impact on the incessant gridlock the city has become so used to.

More importantly, now that gas supply has hit a wall, natural gas usage has to be prioritised in the national interest. With little or no headway in finding viable alternative primary energy resources, we have to take some hard decisions on whether continued usage of CNG at current price level is feasible. Can we afford the luxury of pumping cheap fuel into carriers for the more affluent in society while industry starves? It is hoped policymakers will take these issues into consideration when revising fuel prices in the coming weeks.

The writer is Assistant Editor, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments