SDGs belong to everyone

Over the past three days at the United Nations Headquarters in New York, more than 160 world leaders attended the UN Sustainable Development Summit at the 70th meeting of the UN General Assembly. It was here that leaders formally adopted an ambitious new sustainable development agenda on behalf of their citizens. It is the culmination of three years of inter-governmental negotiations and an unprecedented global consultation that gave voice to millions of people who came together and collectively identified and defined the next development agenda known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Sustainable Development Goals: The People's Agenda

The SDGs build on the achievements of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which end in December this year. While the MDGs were successful in lifting millions out of poverty, there are pending gaps. Globally, 800 million people still live in extreme poverty, 57 million children are still denied the right to primary education, gender inequality continues to persist, and economic gaps between rich and poor households are growing. It is clear that there is still unfinished business.

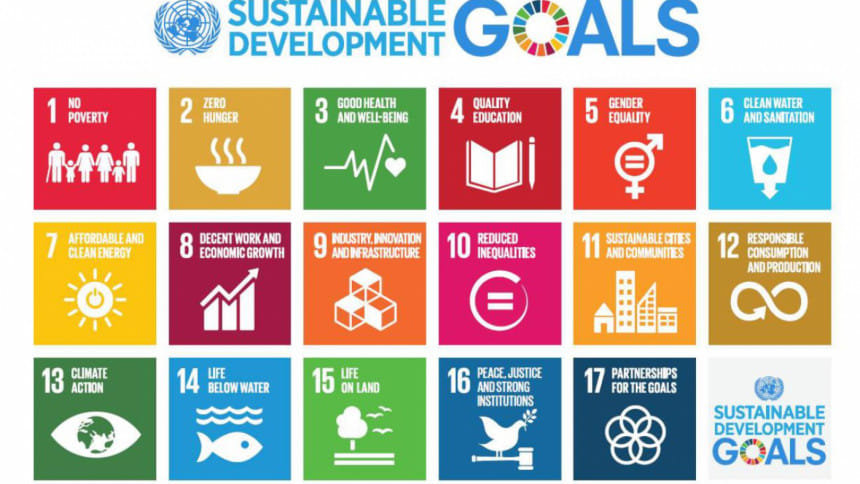

The complex challenges that exist in the world today demand that a wide range of issues be covered but also that there be as wide a consultation as possible to ensure that the world's priorities were identified by people from around the globe. From governments and CSOs to youth, community groups, and individuals, the SDGs were as much driven by governments as they were by the citizens who have the final stake in them. The result is that with 17 goals and 169 targets, the SDGs are broader in scope and more flexible in design. They not only address unfinished business such as the environment, education, health, and gender equality, but acknowledge the importance of the internet and information exchange, the urgency of addressing climate change, and the role not only of industrialisation and infrastructure in equitable economic growth, but the importance of the creators of this growth.

In this way, the SDGs aim to go further than the MDGs by strengthening the facilitators of development and addressing the root causes of poverty. In implementing the next development agenda, economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental protection serve as the compass for a holistic approach to reducing poverty, recognising that many issues affecting the poorest and most vulnerable are interrelated in nature and require multi-dimensional solutions. Crucially, the SDGs are universal, and don't just apply to countries that receive development aid. This contributes to stronger global partnerships and accountability.

The SDGs in Bangladesh

Bangladesh was active in the global consultative process to determine the SDGs, undertaking two national consultations on thematic priorities and on participatory approaches in the means of implementation. One issue highlighted by Bangladesh and echoed by other countries is ensuring the adaptability of a global agenda to a national context. Fourteen of the seventeen SDGs refer to the importance of aligning to national policies, frameworks, and plans, along with nationally defined indicators. This ensures that the SDGs not only reflect the contextual reality of development in the country, but that the goals are nationally owned.

National ownership is not restricted to determining benchmarks for national development, but also generating domestic resources to finance the national development agenda, enhancing inclusiveness, transparency and accountability of institutions and processes, and encouraging active civic participation. Many of the goals Bangladesh proposed as part of the consultations have been incorporated in the final SDG framework, and are also reflected in the Government's 7th Five Year Plan and associated Development Results Framework.

A key area Bangladesh can already begin working on is preparing an institutional arrangement that reflects the integrated approach necessary to implement the SDGs. This can be done through adapting existing coordination for mechanisms such as the Local Consultative Group mechanism of development partners and government. Another element of creating the structures required for implementation of the SDGs is improving the availability and frequency of data for effective monitoring, inclusive of the existing 7th Five Year Plan results framework and national surveys as well as participatory approaches. Suggestions from Bangladesh's national consultations refer to actions such as social audits and participatory planning and budgeting at the local government level, which not only provides accountability, but extends ownership of the SDGs to those with the biggest stake in their success.

Finally, while the SDGs offer a "grocery list" of goals, poverty eradication, shared prosperity, and planetary sustainability cannot be reduced to a simple formula. Bangladesh must determine not only which SDGs are prioritised, but how this prioritisation will take place and in turn, the budget allocation necessary for delivery. This need not be limited to national initiatives, and there is potential for regional solutions that capitalise on opportunities for South-South and Triangular cooperation. While the 7th Five Year Plan provides a template for delivery of the national development agenda, there is also scope for a national prioritisation process that not only educates people about the SDGs, but offers insight into which goals have critical mass support and are deemed to be important for the everyday lives of people. Moreover, the process can be undertaken by government, or alternatively by community groups, NGOs, and CSOs, continuing the open and inclusive spirit of the SDGs.

There is no question that the SDGs are ambitious. Overcoming global poverty requires ambition. In their formation, and in their adoption, the SDGs demonstrate a collective desire to eradicate poverty and strengthen universal peace. There is a cost to human suffering, inequalities, and environmental degradation, stunting a country's ability to prosper, and an individual's ability to contribute to national economies and their own well-being. Development progress is not confined to broad platitudes and noble declarations; it is hard work, and it will take resources, the right policies, and the necessary political will to eventually see a world without poverty. The SDGs don't belong to a single entity, country, or organisation, they belong to all of us. And in this way we all have a part to play.

The writer is the United Nations Resident Coordinator in Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments