Unravelling a forgotten chapter

West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee has done well to declassify the files on Subhas Chandra Bose. Prime Minister Narendra Modi should have followed suit and make available to the public the documents and papers which the Centre possesses on Bose.While declassifying 64 files comprising 12,744 pages, the chief minister informed the media that documents proved the Bose family was spied upon. "It's proven…I will only say it is unfortunate," Banerjee said. The first disclosures in April by a media house revealed a 20-year surveillance on the Bose family, between 1948 and 1968. These were accessed from only two declassified special branch files of around 50 pages. The papers reveal how dozens of spies of the Intelligence Branch, as the state IB was then called, mounted surveillance on Netaji's older brother Sarat Chandra and his sons Ameya Nath Bose and Sisir Kumar Bose.

The IB sleuths intercepted letters at a post office near their residence and tailed the family members around the country, drafting secret reports that were sent to IB headquarters in New Delhi. These early revelations from the huge mass of documents have rightly incensed the Bose family.

"This kind of surveillance is usually done on anti-national elements and not freedom fighters like Sarat Bose," Netaji's grand-nephew Chandra Kumar Bose said. The Bose family has reiterated their demand for a probe by the Centre into the snooping.

A Special Branch letter, from the trove of documents declassified on Friday, reveals the government order which first authorised interception of the Bose family letters from their residences on 38/2, Elgin Road and 1, Woodburn Park, Calcutta (Government Order No. 1735, dated 20/9/48). The special branch cites this letter to ask its headquarters for a one-year extension in the interception period because it had been carried on 'with good results'.

This is a sad reflection on Jawaharlal Nehru. Understandably, the Congress party is quiet. Yet, the party should have privately assured the Bose family that it would have no objection if there were an inquiry to apportion responsibility.

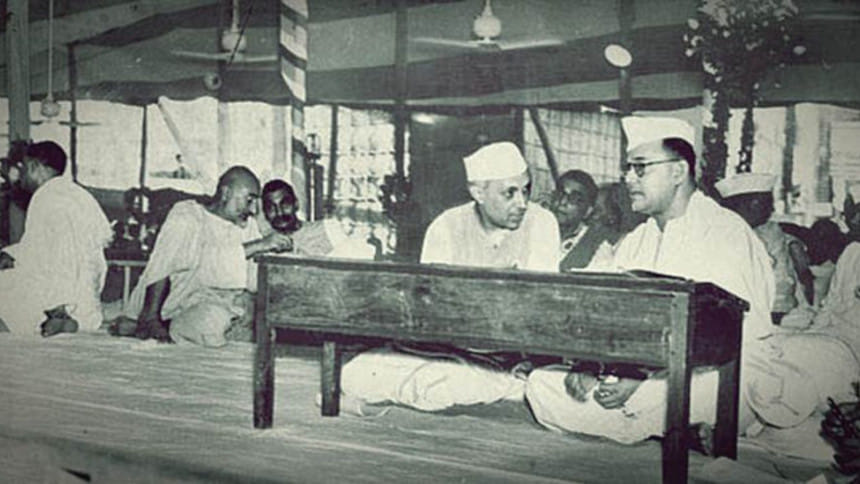

Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose were the two leading lights of national struggle against the British rulers. Both were close lieutenants of Mahatma Gandhi, who was guiding the movement. The difference between the two was that Nehru, distinctly against weapons, had come to have full faith in non-violence as the method against the mighty British masters to win freedom.

Even when he differed with Gandhiji, who found no difference between Germany's Hitler and Great Britain's Winston Churchill, Nehru's sympathy lay with the Allies fighting against the Axis to protect and preserve democracy. For some reasons, Gandhiji had come to believe that Germany would win the war. He took many years to change his viewpoint. But this did affect the thinking of the Congress party leading the national movement.

Nehru often expressed his sympathy with the Allies in the sittings of the Congress Working Committee, the party's apex body. However, he followed Gandhiji who, Nehru believed, would release the country from the British bondage. Bose was clear in his view that violence should be used if necessary. When he escaped from jail in Kolkata, and travelled all the way to Germany through Afghanistan, he thought that there was no harm to get assistance from a dictator to liberate India. (I have visited the two-storey house where Bose spent the night).

With the disclosures of files in Kolkata, a forgotten chapter of India's freedom movement has been restored. Bose, who constructed Indian National Army (INA), with the support of Indians living in South East Asia, has got the spotlight.

There is no doubt that he guided Indians living in South East Asia to establish the INA. Whether the Japanese would have allowed India to live as an independent nation after liberation is difficult to imagine. The fascists had their own agenda and had no place for democratic thinking. But there is no doubting Bose's determination. He would have fought against the Japanese if they had tried to make India their colony.

New Delhi, the centre of the British rule, has the key files. I doubt that when they are made public, the question that would still nag the nation is whether everything had been disclosed or whether some files that showed Nehru in a bad light had been destroyed. One thing which has been proved without any doubt is that the Nehru government was keeping surveillance on the Bose family even after his death in an air crash in 1945.

In fact, the air crash story has come under suspicion after the files were made public. It has become all the more necessary for the central government to throw open all the files and papers relating to Bose. The Narendra Modi government should have no compunction in doing so, whatever the fallout.

One argument advanced for keeping the files secret is that the disclosures may have an adverse effect on relations with foreign countries. How that could be, is not yet explained. The Soviet Union, where Bose took shelter, has disintegrated. Moscow is now a far more liberal place than it was back then. The archives should have some papers to throw light on that period as well.

For some reasons, the Modi government is reluctant to let the nation know the entire story. Whatever his compulsions, PM Modi would ill-serve the democratic norms which demand that the people have the right to know. Surely, he doesn't want to be considered a person who acted as a censor and kept back from people what they had the right to know.

Mamata's remark that what Nehru did was unfortunate will be echoed and may damage his image. But what he did was so un-Nehru like that he deserves to be criticised. Nehru's name is associated with free information, which is essential for a free response in a democratic setup. In view of the disclosures, posterity is going to pass on a harsh judgment against India's icon and first prime minister.

The writer is an eminent Indian columnist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments