When 'empowerment' rings hollow

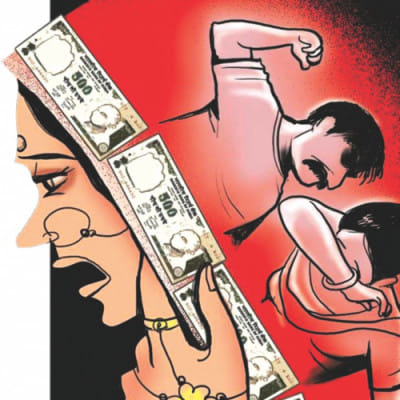

As the whole nation basks in the glory of our success in the cricketing arena, the news of a young housewife's eyes being gouged out by her husband doesn't seem to have gotten its deserved attention. Although the ways in which Shukhi was tied up and maimed with a mobile phone tester were nothing short of barbaric, we are not remotely shocked. The story of Shukhi, who was tortured by her husband and in-laws, is one of many incidents of dowry-related violence that pervades Bangladeshi society and usually goes unreported like many other crimes of violence against women.

Such inhumane crimes in this country have become the norm rather than the exception, and at the risk of sounding pessimistic, such instances of domestic violence often seem to be reduced to "examples" in gender and justice related conferences in academic circles, and good fodder for the media as potential "stories" and/or "headlines." Much has been written in academia and the media about the ills of dowry, how it is falsely justified in the name of religion, and the complex factors at play that perpetuate dowry practices in the South Asian region. But we barely understand that whenever a man chooses to manifest his "physical superiority" over a woman in such a brutal way, it has much more to do with his emotional weakness and moral corruption than physical strength.

To be honest, the term "women's empowerment" starts to seem quite hollow when the higher-ups, who claim that they will tackle gender-based violence, don't assure us that legal action will be taken against assaulters (often the husband) or publicly address these issues in the aftermath of such incidents, further legitimising the culture of impunity where criminals are handed a blank cheque to carry on their heinous acts. Authorities would rather leave it to the media to print a short story on a housewife being beaten in an inconspicuous corner of the backpage until stories of many more Shukhis pile up, eventually being "documented" and preserved as an annual statistic in a report by NGOs. In the midst of these meaningless processes, personal stories of women like Shukhi get lost and we, as a society, continue the pattern of failing to truly empathise as our minds remain occupied with positive stories about cricket.

How do we reconcile "women's empowerment", whatever that means, with such monstrous acts of violence against women? What do we hope to achieve in terms of "women's empowerment", whatever that means, when an overwhelming number of women remain vulnerable to domestic violence? Maybe we should ask ourselves the question: who are the women who are/can be truly "empowered"? Is there any doubt that "women's empowerment" is a class-based, exclusionary notion? Because given the extent to which our society is highly stratified in terms of wealth, "women's empowerment" seems to be reserved for the privileged few. Semantics is important and using terms such as "financially independent" when referring to women garment workers masks the ground reality which is often quite different from derived generalisations, from statistics. How do we define the "financial independence" of garment workers when there are women who, despite having their own income source, almost always need to resort to the help of a male relative to prevent their hard-earned piece of land being grabbed? What does "financial independence" mean to the less privileged when there are countless Shukhis and working women who are dehumanised and their bodies mutilated by their significant other when the latter's demands for dowry are not met?

In a society where dowry deaths and violence against women in general is culturally sanctioned, laws like the Dowry Prohibition Act can do little especially when they're poorly implemented. The way in which Shukhi was ganged up on by her husband and in-laws speaks of a deeper national psyche in which mob mentality and violence against the powerless reigns supreme. The same way 13-year-old Rajon was lynched to death by a group of sadistic adults, the same way around seven women were molested by gangs of unruly youths during Pahela Baishakh celebrations. It speaks of a dangerous need for power and a perverted sense of satisfaction for which these mobs and thugs are willing to gouge out a woman's eye and torture a child to death. It speaks of the laidback mentality and nonchalance of the nation as a whole to such crimes. It speaks of a country full of people who don't feel compelled to react until and unless they're faced with a viral video of a woman or child being abused. It speaks of a nation which seems to have accepted, rather than fight at the grassroots level, regular occurrences of violence against women and children as the norm.

The reductive ways in which we tend to "measure" women's worth, be it through dowry or export revenues of RMG, are alive and well. "Women's empowerment" seems like a convenient illusion when we continue to preserve the very power structures that stand in the way of truly empowering women who need it the most. No number of RMG factories and NGO projects can ameliorate the status of women and stop dowry deaths if we fail to educate, in every sense of the word, both our women and men, and we need to do better than simply "boost literacy rates" by teaching people how to write their name.

The writer is a journalist at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments