Where has the tolerance gone?

SOMETIME ago, a leader in this newspaper wondered what had happened to our sense of decency. The thought-provoking article struck a chord in many hearts, including mine. I have been wondering, in addition, what has happened to another human trait called tolerance. Decency and tolerance often go together. Still, they do not mean the same thing. Of course one can be intolerant without being indecent. I suppose it is quite possible for one to have his enemy taught a good lesson in fairly decent ways. Nevertheless, it is useful to see decency and tolerance as separate traits.

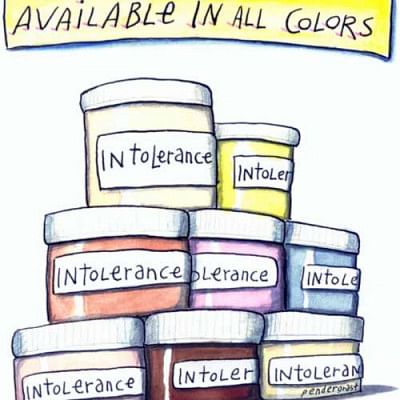

Tolerance will be noted as a noble human trait. Long reflection on the matter has been edging me to the belief that we Bangladeshis are becoming an increasingly intolerant lot. A point has perhaps been reached where rampant intolerance has virtually obscured the idea of decency.

Many years ago a noted Bengali litterateur famously said that all Bengalis are good humans; it is the neighbours who are wicked. This is of course a literary exaggeration and not all of us hate all our neighbours, though some certainly hate some of theirs. And he was talking of individuals, not social groups. Still, he would have been amazed to see how intolerant we have become as social animals. Intolerance today goes far beyond mere neighbourly ill-feeling.

Physical violence is of course the most blatant manifestation of intolerance. No society is ever free of it, but its nature changes over time. Not so long ago, the most important instances of violence in our society arose from dispute over possession of land. Today, intolerance and violence that take on 'political' colour dominate the social landscape. There is a widespread feeling in the country that violence fostered by politics is sharply on the rise. Much of this takes the shape of inter-group as well as intra-group rivalries. A recent newspaper report suggests that the number of people killed in the past few years as a result of factional rivalries within the 'student' and youth wings of the ruling political party can be counted in the hundreds. Long knives, fat bamboo logs, and even handguns are freely used in intra-group fights. Newspaper photographs of marauding 'students' are among the common media sights. Rivalries that lead to violence are rampart among the corresponding wings of the party in opposition as well. Those of us who remember student politics of the 1950s and a little later will recollect that an occasional push or shove was generally all that happened between factions. One is tempted to ask, what has changed? Perhaps a good hypothesis is the monetisation of politics. Tolerance vanished as lucre took over.

The orgy of violence in the run-up to the January 5, 2014 general election was commonly seen as something unprecedented. The rage behind it was entirely political: the Bangladesh Nationalist Party's demand for elections under a caretaker government collided with the Awami League's insistence on holding them under the current government. Some would argue that the feud was not so much over their claim to championship of democracy; it was more a reflection of the sorry state of the personal relationship between the paramount chiefs of the two parties. Tolerance has been the chief victim of the impasse. The Jamat-e- Islami's reaction to the trial and conviction of many of its leaders for war crimes further fuelled the pre-election political rage. The period of remarkable post-election calm did not last and we are now in the midst of the longest era of unmitigated political violence in the nation's history. The halcyon days of families merely being intolerant of their neighbours, or where violence is confined to an occasional flare-up over possession of land, seem to have gone forever. Nowadays, intolerance translates into indiscriminate killing. Unconscionably, the instrument of the killers' choice is arson. Burning vehicles, charred human bodies, and burnt men, women and children in agony in crowded hospitals are common sights in the media.

Perhaps violence of this nature will abate in the not too distant future and a semblance of normalcy will be restored in the relationship between the main political parties. It is hard to see other kinds of intolerance going away anytime soon. They appear ingrained in our national psyche. And there are a great number of areas where tolerance often abandons us. Use of abusive language about prominent national leaders can land the perpetrator in jail. Contrast this with prime ministers or presidents in Europe and America taking all kinds of criticism and even insults in their stride. The British prime minister is routinely subjected to ridicule, which he routinely ignores.The US president does not care if someone calls him stupid, which of course he is not.

The killing of Avijit Roy represents an entirely different genre of intolerance, one which is also an increasingly menacing kind. It also has immense consequences for our society. Roy, author of several thought-provoking books, free-thinker and blogger, was murdered on the evening of February 26 this year. He was killed, as the writer Humayun Azad was only a few years earlier, because of his views. A person's views, lest we forget, is a fundamental right enshrined in the country's constitution. Roy's views were based on reason and scientific evidence. He rejected what did not stand the test of reason. He debunked what to him was superstition and blind faith. And in all of this he was of course following the path laid out by the great inquiring minds of history who revolutionised the way we look at the world around us and beyond. Some of these great minds were more critical of faith than others. Roy undoubtedly belonged to the critical school of thought. It is precisely such thinking that proponents of modern Islamic radicalism found it difficult to tolerate. They had been threatening the undaunted Roy for some time and finally killed him. They have been threatening other free-thinkers too, and there is little reason to suppose that they will not bring out the long knife again soon.

Such killers are never found and brought to justice. That is among a long list of reasons why radical Islam continues to be a threat to rational thinking and free speech. I am inclined to suggest a list which will also include a virtual competition among political parties to demonstrate that they are better Muslims than their opponents. Defending a person of dubious religious commitment is also politically inconvenient at best. Hard to ignore too is a certain pusillanimity of the mainstream media.

Intolerance extends far beyond the rage to kill a few 'atheists.' People who are merely liberal and who even give a wide berth to those who harbour critical thoughts on religion, have also often been subject to threats for their alleged 'insult' to faith. The fuzzy idea of 'hurting the religious sentiment' of Muslims has often been used to raise hackles. It is enough, for example, for a cartoon that was not intended to insult the prophet of Islam, but was construed by some to have been so designed, to heighten passion and raise demand for the culprits' imprisonment or even worse retribution.

Can we hope to see a significantly more tolerant society in the foreseeable future? No. There is no magic wand to remove intolerance from society. Still, can we afford not to talk about them openly and loudly?

The author is a former United Nations economist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments