The peculiar global invisibility of 1971

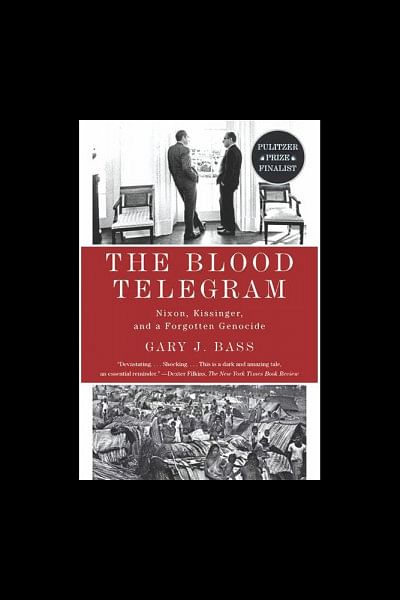

A few years ago, I attended a book launch event for Gary Bass's The Blood Telegram (2013) at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in downtown Washington, DC. Bass spoke convincingly about the topic of his well-researched book: that is, how, in 1971, former East Pakistan's Bengalis became tragic victims of the disgraceful foreign policy of the Nixon White House and its dehumanising Cold-War geopolitics.

I found the book's subtitle curious: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Archer K. Blood, the American Consul General in East Pakistan (1970-71), most likely first used the term "genocide" on March 28, 1971, to describe what was then going on in East Pakistan. I was particularly struck by Bass's expression of "a forgotten genocide."

During the question-and-answer session following his talk, I asked Bass about the subtitle. Who exactly forgot the genocide? The US? The world? The conscience of history? Does not forgetting something as grave as a genocide assume that it was at some point in the pastwidely accepted as such? If that is the case, how does the world decide which genocide to remember and which to forget? Isn't it strange that the world conscience continues to be horrified by the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, the Indian Partition, the Khmer Rouge killings, and the Rwandan massacre, while forgetting the genocide in Bangladesh in 1971? How does one explain this peculiar politics of "selective amnesia"?

Bass replied that as a journalist and professor of politics his task in The Blood Telegram was to exclusively focus on East Pakistan's tragedy and how the Nixon-Kissinger-Yahya nexus perpetuated it. What I was asking, he said, was a larger philosophical question of how histories are written and by whom and when. Since he was not a historian, he would not be able to satisfactorily respond to this historiographic riddle.

Fair enough.

Ever since I have wondered whose fault it is that the 1971 mass atrocities in Bangladesh still remain largely overlooked in global histories of genocide. In 2013, a New York Times reviewer of Bass's book calledthe 1971 massacres a "terrible and little-known story of the birth of Bangladesh." The title of a recent Smithsonian magazine article, titled "The genocide the US can't remember, but Bangladesh can't forget," pretty much sums up how the world, and the US in particular, views what happened in Bangladesh in 1971. A sordid little story.

It is astounding that given the scale of the Bangladesh genocide and its global significance, there are sadly very few authoritative, well-researched books on the subject. I can think of only two other books beyond Bass's: Richard Sisson and Leo E. Rose's War and Secession: Pakistan, India, and the Creation of Bangladesh (1990) and Srinath Raghavan's1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh (2013). While not history in a canonical sense, Archer Blood's The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh: Memoirs of an American Diplomat (2002) is a useful resource.

The bottom line is that there are not many insightful, evidence-based books on the liberation war of Bangladesh. So, whose fault is it that there is a dearth of research on the topic? Why is Bangladesh's genocide not a consistent part of global histories?

It would be virtually impossible to pinpoint a reason or reasons why more scholars and historians around the world are not interested in the topic. This question itself warrants sustained research. Any PhD student out there?

Instead, let's look inward. How culpable are we, Bangladeshis, in the relative invisibility of the 1971 genocide on the world stage? Why haven't WE been able to produce a panorama of interpretations of how we came about as a nation? Why hasn't there been a world-class biography of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman? Are we too emotionally-driven a nation that we are unknowingly afraid of going beyond self-satisfying narratives?

To produce dispassionate historians from among its citizens, a nation needs to be confident of both its promises and flaws. The root cause of the problem of why we can't produce nuanced, interpretive histories is how we conventionally understand the very notion of history.

What is history, really? History doesn't exist out there as a ready-made body of facts. The belief that the historian objectively assembles all "facts" out there to create history is spectacularly false.In reading a past occurrence, a historian invariably chooses what to highlight and what to omit.The historian can't avoid the problems of subjectivity. Based on his or her political inclinations, the historian decides to narrate a "story" from a particular vantage point. Some do it well (based on methodological clarity, facts, and evidence) and some don't. Thus, the idea of ONE "shothik itihash" is a mythology. Fact and fiction are more inseparably intertwined than we have been led to believe.One way or the other, history is a political project. This is one fundamental lesson I learned as a graduate student decades ago by reading such authors as Michel Foucault and Edward Said.

The word for "history" in Sanskrit is itihasa, which has traditionally meant "that's what happened" or "so indeed it was." Yet, iti (as in itihasa) is often used in a Sanskrit sense of "end quote." Itihasa, therefore, in its traditional usage has often been infused with a host of subjectivities. In other words, history implies not so much what happened as what people said or thought happened. Therefore, historical inquiries necessarily need multidisciplinary, cross-geographical, interpretive perspectives, and, most of all, a dispassionate distance from the subject of inquiry.

Although there are increasing efforts here and there, Bangladesh's mainstream educational system doesn't actively promote research as a mode of intellectual inquiry. The unfortunate culture of not valuing research and knowledge production perpetuates an educational system that only feeds off recycled wisdom. To advance socially, it is important for a people to be proactive knowledge producers. The key is not "shothik itihash" (which doesn't really exist), but histories based on material evidence and archival research, not hearsay, not hagiography.

It is crucial to create a research-based learning environment that would facilitate the rise of a new generation of Bangladeshi historians—with a good command of multiple languages—writing global histories of 1971. As much as they examine archives across Bangladesh and interview surviving members of mukti bahini and rape victims, they need to dig into the archives in Washington, Moscow, Beijing, London, New Delhi, Kolkata, and Islamabad, among other cities. Research is not cheap. We need to robustly invest in competitive research granstmanship among graduate students.

The new generation of historians will create complex historical tapestries of what happened in 1971 and how and why. Perhaps from the work of a new crop of historians will emerge, say, the 1971-equivalent of Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List (1993) or the Bangabandhu-version of Richard Attenborough's Gandhi (1982).

The price of not having a healthy culture of writing interpretive histories is huge. Inept or sensationalist scholars will naturally fill the vacuum. One example, alas, is Sarmila Bose's faux history in Dead Reckoning: Memories of the 1971 Bangladesh War (2011), which is based mainly on "interviews" (in Pakistan, mostly retired army officers were interviewed!), calling into question whether interviews could be a reliable source for reconstructing the past, particularly when there is so much partisan emotional investment. Furthermore, Bose appears too eager to write a "revisionist history" (meaning she has to overturn the dominant narrative!)—at times just for the sake of it. She naively accepts the Pakistani army's "just-trying-to-do-our-duty" justifications, while ignoring the glaring asymmetry in military powers thatexisted between the two feuding parties. Bose's claim that her book seeks to "reconstruct what really happened on the basis of available evidence" is, sadly, a testament to what historians in Bangladesh didn't do: produce their version of "what really happened on the basis of available evidence."

The unfinished project of history in Bangladesh requires robust public- and private-sector investments in research-driven liberal-arts education. The spirit of 1971—which is hardly a monolithic narrative—can be best nurtured by looking back at this momentous year with a self-critical conscience. Bangladeshi historians have to play proactive roles in how Bangladesh's genocide is incorporated into global histories.

The writer is an architect, architectural historian, and urbanist and teaches in Washington, DC. He is the author of Impossible Heights: Skyscrapers, Flight, and the Master Builder (2015) and Oculus: A Decade of Insights in Bangladeshi Affairs (2012). He is a member of the USA-based Bangladesh Development Initiative (BDI).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments