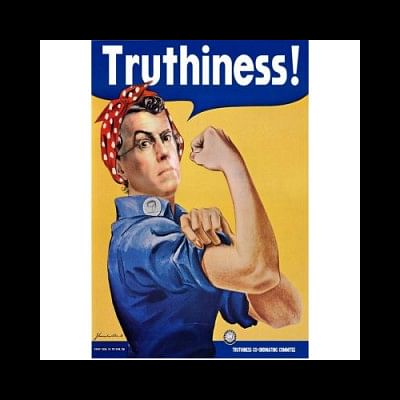

Truthiness on the March

The late US Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously said, "Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts." That may be true. But, entitled or not, politicians and electorates are constructing their own alternate realities – with far-reaching consequences.

Nowadays, facts and truth are becoming increasingly difficult to uphold in politics (and in business and even sports). They are being replaced with what the American comedian Stephen Colbert calls "truthiness": the expression of gut feelings or opinions as valid statements of fact. This year might be considered one of peak truthiness.

To make good decisions, voters need to assess reliable facts, from economic data to terrorism analysis, presented transparently and without bias. But, today, talking heads on television would rather attack those with expertise in these areas. And ambitious political figures – from the leaders of the Brexit campaign in the United Kingdom to US Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump – dismiss the facts altogether.

The environment is ripe for such behaviour. Voters, particularly in the advanced economies, are jaded by years of broken political promises, revelations of cover-ups, and relentless political and media spin. Opaque or dubious dealings have cast doubt on the integrity of organisations and institutions on which we should be able to rely. For example, the New York Times recently published a series of articles on think tanks that highlighted the conflict of interest faced by those who operate as analysts, but are beholden to corporate funders and sometimes also act as lobbyists.

As soon as a few experts are found to have been offering half-truths – or worse – the credibility of the entire field can be called into question. Christine Todd Whitman, who was Head of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on September 11, 2001, told residents of New York City that the air was safe to breathe and the water was safe to drink in the days after the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. But, as a 2003 EPA report noted, the agency "did not have sufficient data and analyses to make such a blanket statement" at that time. With cases of severe respiratory illness piling up, Whitman now admits that the statement was wrong.

Likewise, as the recently published Chilcot report showed, the Iraq War was launched in 2003 under false pretenses. Intelligence reports had not established that there were weapons of mass destruction in the country, yet British Prime Minister Tony Blair dutifully followed US President George W. Bush in ordering his military to invade. The consequences of that decision are still emerging.

If our leaders can be so willfully wrong about such consequential matters, how can we believe anything they tell us? This question has opened the door for a new, more overt truthiness, espoused by the likes of Trump, who seems to introduce freshly invented "facts" on a daily basis. Trump's surrogates, for their part, use television appearances and social media to restate the falsehoods, seemingly operating under the principle that if you repeat something often enough, it will become true.

And many voters seem willing to go along for the ride. When 40 leading Republican foreign policymakers and national-security experts signed a letter expressing their opposition to Trump, whom they fear would be "the most reckless president in American history," their concerns were largely disregarded. Trump's response – that those leaders are the ones who made the world "such a dangerous place" – sounds just plausible enough to justify ignoring their warning. Even outright lies spoken in a nationally broadcast interview go unchallenged, as if Trump were indeed entitled to his own facts.

The leaders of the UK's campaign to withdraw from the European Union enjoyed a similar advantage in the run-up to June's Brexit referendum. They painted a wholly false picture of the country's circumstances – from its role in the EU to the impact of immigration – and knowingly made impossible promises about what would happen if the public voted "Leave."

For example, leaders like Boris Johnson, now Britain's foreign secretary, declared that the £350 million ($465 million) supposedly paid weekly to the EU (a deeply flawed figure that fails to take into account the benefits received) would be redirected to the National Health Services. The Leave campaign even plastered the pledge onto the side of a campaign bus.

Now that the referendum is over, Johnson and others have backtracked, and the campaign has rebranded itself the "Change Britain" movement and promised to redirect EU funds to other areas instead. This has infuriated many, especially given the recent warning by the body that represents hospitals across England that underfunding has pushed the NHS to the brink. Brexiteers have also walked back pledges to curb immigration, amid a sharp increase in hate crimes across the UK that their rhetoric helped to fuel.

The downsides of Brexit should have been obvious to voters before the referendum – not least because so many economists, defense experts, and world leaders spelled them out during the campaign. But, as leading Brexiteer Michael Gove proudly observed, people in the UK had "had enough of experts."

In fact, it seems that some people voted for Brexit specifically because so many experts spoke out against it. They seemed to believe Brexiteer MP Gisela Stuart: "the only expert that matters" is the voter. It should be no surprise that the post-referendum reality is not what many Brexit voters expected.

Yet the revelations of the falsehoods that propelled the Leave campaign to victory have hardly driven people back into the arms of experts. Truthiness is on the march, particularly across Europe and the US – in large part because so many of the authorities who should be calling out the lies are tainted by truthiness themselves.

The writer is CEO of Marcus Venture Consulting.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2016.

www.project-syndicate.org

(Exclusive to The Daily Star)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments