Uri is only a symptom

Baluchis-tan in Pakistan is like our Kashmir, an integral part but still rebellious after almost 70 years of Maharaja Hari Singh's accession to India. However, in India's case first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru gave an undertaking to hold a plebiscite as soon as things had settled in the valley. He could not fulfil the promise.

Nehru found out that things will be reduced to a slogan, Gita versus Koran, and people would be so driven by religious sentiments that they would not be exercising their franchise. When the acclaimed leader Sheikh Abdullah joined the Union, he conceded the point that a popular verdict had been obtained and it amounted to a plebiscite and, with it, the accession was complete.

What happened in Uri is a symptom, not the disease. The disease is that the youth which is now leading a movement want a country of their own. In the same way, Baluchistan wants to secede from Pakistan and have an independent country. That, if granted, would be another Islamic country on our border.

I told the Kashmiri students during my recent visit to Srinagar at their invitation that the Lok Sabha would be in no mood to endorse anything like what they wished. They said it was "your problem how you bring about the change." The demand by the youth for an independent sovereign country is in contrast to what leaders like Yasin Malik and Shabbir Shah had wanted some years ago. It is another matter that Yasin has now joined the chorus.

Pakistan has now become relevant for the people in the valley because they, too, have changed their demand from autonomy to an Islamic independent country. The attack on the Indian soldiers on the border is the culmination of their anger. Pakistan, too, has found the climate somewhat suited to it and has increased the number of infiltrators into the valley.

But this is not the first time that Pakistan has sent infiltrators into India. Nor will it be the last occasion. There have been several such instances, including the attacks on Indian Parliament, Mumbai and Pathankot. After every such incident, a war-like cry was heard in the rest of the country to retaliate. So immense was the pressure this time on the government that it had to assure the public that "retaliation would take place at a place and time of our liking."

But people want action on the ground even at the expense of a war. I recall what happened soon after the attacks on Parliament, Mumbai or Pathankot. Our reaction then was in the shape of stationing troops on the borders for almost one year or beyond. This time, the anger is deeper and wider. Yet the government is showing restraint, though Prime Minister Narendra Modi has assured that the perpetrators would not go unpunished.

However, we also know the limit to which the elected rulers can go in the two countries since both possess nuclear weapons. But what I fail to understand is why Islamabad had been reluctant to take action against terrorists who have been identified living in Pakistan. Whatever it has done so far against the terrorists, it is not on India's request but on Washington's word.

In India, except for a few warmongers, there is a realisation that there is no option to peace. It is also time for the politicians of the two countries to introspect their conduct. Even if they do not talk about war, their speeches and the body language is far from friendly. They appear to run with the hare and hunt with the hound. Why are they stoking the fires of hatred when people on both sides are surcharged?

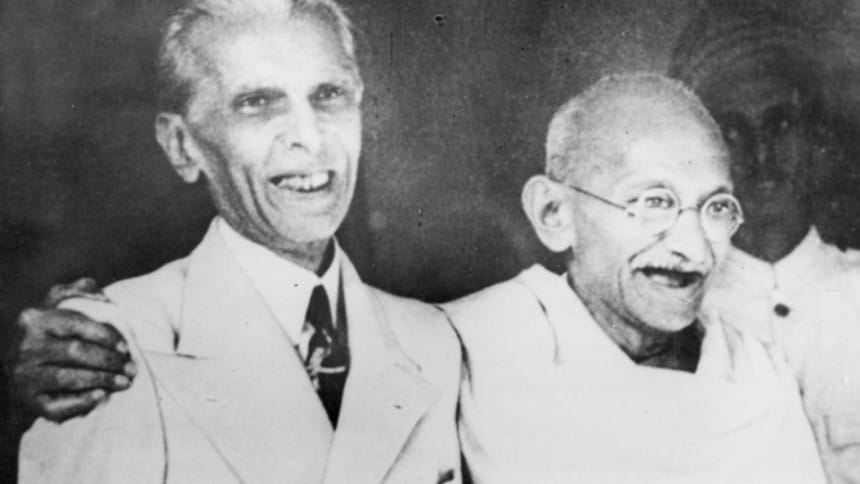

France and Germany had fought for more than hundred years. Today they are the best of friends. Qaide-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah gave me this example when I asked him before partition that Hindus and Muslims would jump at each other's throat once the British had left. He said we would be the best of friends. I have no doubt that one day this would come about. Former Prime Ministers Atal Behari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh have said many a time that the destiny has thrown India and Pakistan together and they cannot but be good neighbours.

I admired the courage and commitment of people, however small in number, lighting candles at Karachi or taking out a procession at Lahore some years ago in memory of those who had died in the Mumbai attack. This is the time when India needs understanding. This is also the occasion when faith in good relations between India and Pakistan is tested.

But at the same time, Pakistan should understand and appreciate India's anger. Those who attacked Mumbai or Pathankot might be the Al-Qaida and the Taliban who are playing havoc in Pakistan as well. These are the organisations which are helping, training and arming them. Why have such extremists remained beyond the pale of law? Even when some of them were "detained" after the attack on India's Parliament, they were practically free to preach and spread poison. India suspects that those arrested after the Mumbai carnage would have the front door of their house shut while the back door was open.

No world power, except Germany, has directly accused the Pakistan government for the attacks on Mumbai. Investigators believe that all attacks on India are linked to members of one terrorist group or the other in Pakistan. Whatever evidence that had India provided in the past Pakistan has failed to prod Islamabad.

The National Investigation Agency (NIA), which is probing into the recent Uri incident, was set up with a fanfare in 2009 to assuage public anger over a similar series of failure leading up to 26/11. They were entrusted with cases but the result so far has been dismal. What the NIA will do in the present case is to be seen. The nation is waiting for a retaliatory action.

The writer is an eminent Indian columnist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments