What's in a word?

Nelson Mandela aptly said: "If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart".

There is something magical about one's native language. It's the glue that holds people together and provides a sense of comfort and security. Language also helps transcend geographical boundaries and religious divides, creating strong cultural and social bonds. My Indian friends who recently visited Dhaka observed that after the half-hour international flight from Kolkata, it felt like they had come home! I feel the same when I travel the other way. So, what is it that makes a foreign land seem like "home"? Is it just language or something beyond?

More than 70 years ago, Benjamin Lee Whorf, a chemical engineer who moonlighted as an anthropology lecturer at Yale University, introduced a novel idea about language's power over the mind, highlighting the fact that our mother tongue significantly influences the development of our thoughts. Whorf's theory was discredited due to the absence of evidence. Unsurprisingly, in the last few years, new research has partially reaffirmed Whorf's claims that when we learn our mother tongue, we acquire certain ways of thinking. Since speech is cultivated from a very early age, it is only natural that it can go beyond language, affecting our experiences, perceptions, associations, feelings, memories and orientation in the world.

The fact is that the language we learn as a child always remains our "first language", or our preferred language. I have been living in an English speaking country for more than half my life. Yet, each time I leave my familiar environ and cross over to the other side, it takes me a while to accustom myself to the unfamiliar sounds and rhythms. I yearn for my mother tongue with its seductive lilt of thea's and o's. And, I still haven't learnt to twirl my r's the way native English speakers do. When I experience a beautiful sunset, I am reminded not of Eliot's "evening" "spread out against the sky, like a patient etherised upon a table" but of Tagore's "godhuli logone badolo gogone" (The twilight moment of the cloud-filled sky). Sadly, I have not been able to find an apt English translation for "godhuli" (twilight?) despite the fact that its orange hue colours the inner recesses of my heart each time I gaze at an evening sky.

While reflecting on the ways my mother tongue has influenced me, there is one particular incident that comes to mind. In 1969, when I had just started singing publicly, I selected a Tagore number, "Aji Bangladesher hridoy hote"(You have emerged from the heart of Bangladesh, my Mother, in all your glory and splendour) for a radio rendition. The broadcasting authorities of the then East Pakistan informed me that the song could not be aired since it contained metaphorical references to the goddess "Durga", comparing her to Bangladesh, the motherland. I was shocked at the narrow and biased interpretation of the lyrics. Above all, I was frustrated that the freedom to express my love for my country in the words of the most revered poet of Bengal had been curbed. It was a time when turbulent tides of change were sweeping through the region - the country was overpowered by a surge of patriotism that sowed the seeds of Bengali nationalism. Tagore's literary works were an integral part of this movement.

The resistance I encountered from the radio administration left such a strong impression on my mind that I felt compelled to join the fight for an independent Bangladesh. Through this experience, I realised that the struggle for Bangladesh's independence and the struggle for expressing our thoughts and ideas in our native tongue were deeply intertwined.

Recently, I was dismayed to read a news report that the very same song, "Aji Bangladesher hridoy hote", has been deleted from Bengali textbooks under pressure from communal forces. There is a sense of deja vu - as if we are living through another wave of attack on Bangla culture and language. It appears that the extremist groups have once again intensified their attempts to communalise the country. Their efforts are now focused on influencing impressionable young people, using one of the most effective tools – the language that shapes their perceptions of the world.

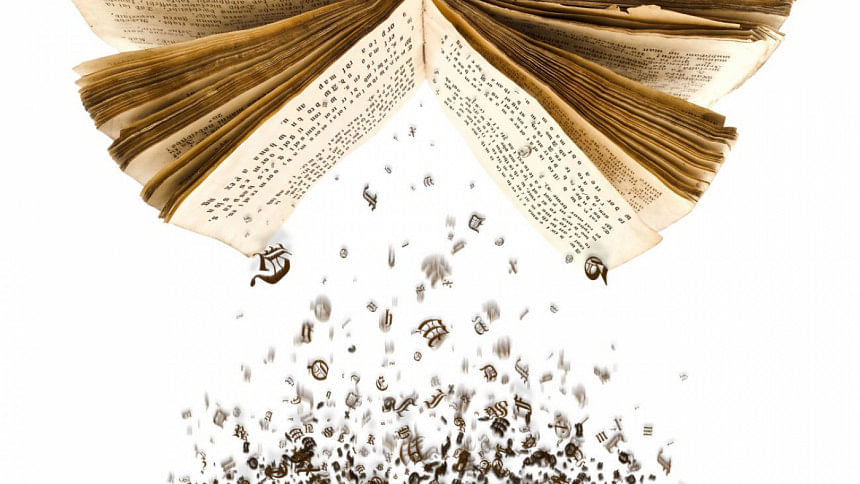

This month, as we pay homage to the martyrs who helped reinstate our language and identity, it may be time to renew our vow to protect and preserve Bangla from the onslaught of extremist forces. For language is not just a means of communication – it helps in the development of personality and character. As our mental horizons widen, as our intellectual boundaries expand, and as we navigate through the maze of information in the internet era, our native tongue keeps us anchored to our basic values and traditions. If we want to promote secular ideas and activities in public spaces, we must ensure that our mother tongue is not artificially choreographed to sway the views and beliefs of our youth toward extremism and bigotry. Most importantly, the national narrative propagated through our mother tongue must reflect the diversity and tolerance that are deeply embedded in our society.

The writer is a renowned Rabindra Sangeet exponent and a former employee of the World Bank.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments