Schools are finally reopening, but what’s next?

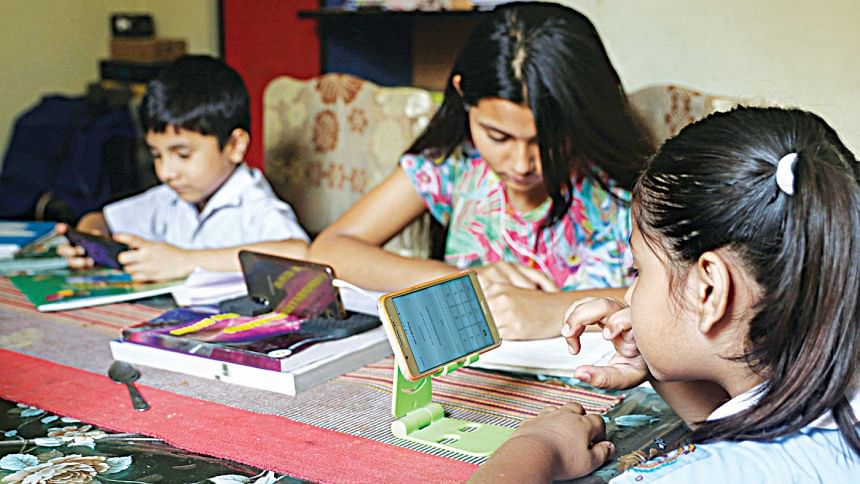

The government's decision to open educational institutions is a welcome development. All educational institutions have remained closed since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, and the promise of online education has failed miserably to deliver. The failure was not unexpected in a country where mobile internet speed is very poor. Bangladesh is one of the five countries on the bottom of the global list when it comes to mobile internet speed.

We are all aware of the steps taken by the government to tackle the pandemic. A few rounds of the so-called "lockdown," announcements of several stimulus packages and the occasional vaccination "festival" marked the last 18 months. What remained constant during this period was the closure of educational institutions. Everything else has continued as if the pandemic does not exist, or normalcy has returned after brief disruptions. But the doors of educational institutions have remained stubbornly locked, although we heard repeated announcements that they will be opened soon.

Bangladesh is among the few countries in the world where the educational institutions are still closed due to the coronavirus. In fact, considering the length of the closure, Bangladesh ranks second in the world. Educational institutions have been closed since March 17 last year, and now it has been said that primary, secondary and higher secondary-level educational institutions can be opened from September 12. As for universities, they may soon follow, with the Dhaka University vice-chancellor stating that the university is likely to open in phases in October.

Three of the long-term effects of the coronavirus around the world are particularly significant. First is its impact on the educational sector. A generation will lag behind others because schools and colleges have been closed for so long or the students have not been taught in usual ways. Even in countries where educational institutions have been closed for a short period of time, this has remained a major concern. The closure has caused high rates of dropout; bringing these children back to school remains a challenge. Secondly, there has been a decline in nutritional intake among low-income people. Due to reduced income, poor people have suffered from food scarcity, and as such, malnutrition will increase among a significant segment of the society. It is not only the poor that will bear the brunt of it—the middle class will also be equally affected. The third effect is the increase in income inequality. Even during the epidemic, the rich have become richer all around the world. Bangladesh is not immune to these three adverse impacts.

It is against this backdrop that the educational institutions remain closed. Public health theories cannot explain why the government thought that infection would be higher from the crowd of schoolgoers than from the crowd of people thronging shopping malls or ferry ghats, but recent comments by ministers, made either willingly or inadvertently, provide the clue—it is sheer politics. As some university teachers started taking symbolic classes, and Unicef insisted on July 12 that schools should be opened, the government seemed to have felt the need to make a move. Over the past several months, the government claimed to be preparing for the opening of the educational institutions, but what those "preparations" have been is yet to be known. I hope the government and school-college authorities understand the difference between opening the institutions after any other holiday and opening now.

The government did not say whether school and college teachers are included as a priority on the vaccination list. It is also not known who will be responsible for ensuring that teachers and students wear masks, and conducting testing on a regular basis for the foreseeable future. Students and parents need to know what measures will be taken if the number of infections increases. What is the threshold of keeping an institution open? Will there be contact tracing?

It is important to ensure that government schools and colleges receive additional funding in order to adhere to the health guidelines; monitoring will be necessary to see whether they are being properly spent. If the government thinks that its only responsibility is the announcement of a date, then they are misjudging the scale of this task. According to Education Minister Dipu Moni, "We have already made preparations for the opening of schools and colleges." Have these measures been communicated to citizens and parents? The government should draw on the experience of other countries, especially those sharing socio-economic similarities with Bangladesh, not of countries in Europe or North America.

The severe loss in the education sector caused by the pandemic, especially due to the long closure, will not be recouped only by opening the schools and colleges. There was always discrimination in the sector due to the unjust social system; it has increased manifold over the last year and a half. Children of the rich and upper-middle class families have been able to continue their studies, many with the help of private tutors, whereas children of the poorer families were left with no support. This has pushed them one step backward.

Merely unlocking the doors of schools and colleges will not be sufficient to bring back those who have dropped out of the system. A study by Brac and Manusher Jonno Foundation showed that child marriage has increased by 13 percent due to the closure of educational institutions during Covid-19—the highest in 25 years (Deutsche Welle, August 24, 2021). The government must take the initiative to reach out to the families who won't be able to send their children to schools as their primary breadwinners have lost their jobs or their income has dropped remarkably. School authorities as well as NGOs can join hands to identify these families. In short, this requires a coordinated plan. Does the government have that plan?

The university authorities will decide when universities will be opened. Authorities of Dhaka University have given the impression that they have prepared a road map. It is said that all students at the university will be brought under the immunisation programme by September 15. The residential halls are gradually being opened. But the question is whether the government has enough vaccine in stock to inoculate all universities students. It is also not clear what measures are being taken by other public universities. Public health considerations must prevail in making the decision to reopen, but other considerations should not be ignored. For example, the university administrations now have the opportunity to address the so-called "gonoroom" culture in various dormitories. This practice handed over the fate of many students to the Chhatra League leaders who control those rooms. Indeed, considering the past behaviour of university administrations and their political proclivities, a change is unlikely. But if they could do away with this culture, at least one good thing would come out of the long closure of universities.

Ali Riaz is a distinguished professor of political science at Illinois State University, a non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council, and the president of the American Institute of Bangladesh Studies (AIBS).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments