Beijing’s Catch-22

It's been just 22 years since Hong Kong reverted to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, after 156 years of British colonial rule. Recent events in Hong Kong suggest that the long British rule has left considerable English influence on the ethnic Chinese of the region. Though the older English-speaking generation is on the wane, the young English-speaking millennials seem to be spearheading a political movement for democracy and social justice.

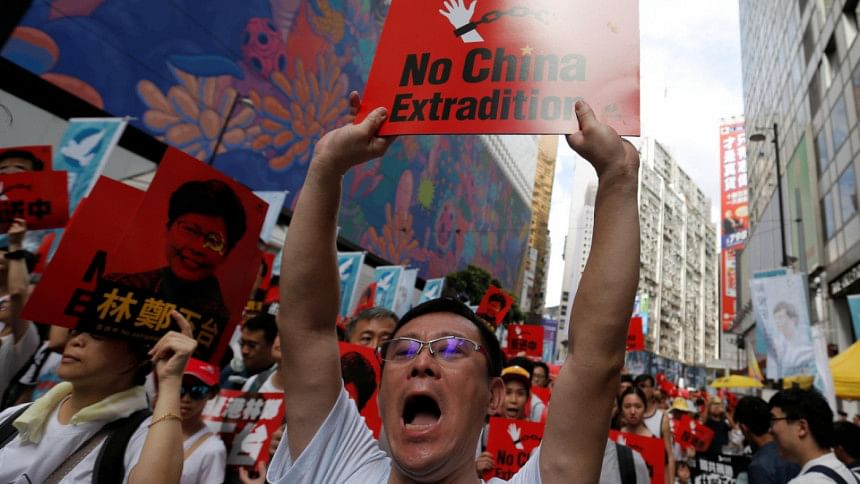

After months of escalating protests against the extradition bill to China that Hong Kong's Chief Executive Carrie Lam wanted to pass through the Legislative Council (Legco), it appears that a shaken Beijing is now sitting up and contemplating to govern Hong Kong rather than administering the region. As the trust gap between the protesters and the Carrie Lam administration grew wider, demands for the chief executive's resignation also came up forcefully from the demonstrators.

Actually, the protests have a background that goes well into the British period. In the early 1980s, Britain and China prepared for the transfer of the territory to Chinese sovereignty and singed the Joint Declaration in 1984. The Joint Declaration ensured "one country, two systems" for Hong Kong after transfer of sovereignty in 1997. Hong Kong, known as a special administrative region (SAR), was to retain for the next 50 years all its Basic Law (mini-constitution of Hong Kong) features—capitalistic economic system, its own currency, legal system, and so on, except foreign policy, defence and interpretation of Basic Law: three subjects which were under Beijing's control.

Under the Basic Law, Hong Kong has a distinct autonomous identity but is subordinated to Chinese sovereignty. The Chinese renminbi is not legal tender in Hong Kong, as Hong Kong dollar is not accepted in mainland Chinese shops. Residents of Hong Kong do not hold Chinese passports but Hong Kong SAR passports. The official languages in Hong Kong are English and Cantonese while in the mainland, it is Mandarin. Ethnic Chinese in Hong Kong refuse to identify themselves as Chinese, according to a study by Hong Kong University.

Britain, which prides itself on its democracy, never allowed direct election in the territory. It appointed the governor and also Hong Kong's 70-member Legco. Fearing monolithic Chinese Communist Party rule after 1997, there were agitations in 1986 in Hong Kong for universal suffrage. The demand for a directly elected Legco and governor/chief executive grew successively larger over the years. However, in an astute move, Britain allowed direct election for the Legco in 1995, just two years before the hand-over of the port city to China. Hong Kong residents were elated that the system would continue under Beijing's rule and they would enjoy more freedom and social justice. That hope was dashed when, on the night of the transfer of sovereignty on July 1, 1997, Beijing dissolved the Legco.

However, since 2000, Beijing gradually allowed direct election to 35 seats of the Legco, but continues to appoint the remaining 35 from the "functional group" of lawyers, bankers, trade union leaders, etc. The pro-China group of members currently has majority in the Legco. The chief executive is still appointed by Beijing. In 2014, the Umbrella Movement—also known as Occupy Movement—was born when thousands of protesters used yellow umbrellas to fend off pepper spray from police. Demonstrators wanted Beijing to desist from vetting the candidates for the chief executive post. Many young student leaders were arrested by the police at that time.

But the undaunted millennials have continued with their agitation for democracy. What is happening now is a sequel to the movement that was born in the mid-1980s. They fear that the principles of the Basic Law would be tampered with by Beijing. Since early February 2019, young school and college students descended onto the streets to protest against the extradition law, which, if passed by Legco, would allow the Hong Kong administration to extradite anyone charged with any offence to mainland China to face trial in Chinese courts. Carrie Lam has declared that the bill is now "dead".

Actually, the resistance by the protesters is to deny Beijing its powers of sovereignty over Hong Kong. They do not want Beijing to dilute Hong Kong's legal system and civil liberties. The protests involving tens of thousands of young millennials have been growing with each passing week, and are becoming increasingly violent. Clashes with police and arrests are a regular development now. On July 1, a group of protesters entered the Legco building and vandalised it. There have also been attacks on the protesters recently at an underground metro station, meaning that the territory is definitely divided between the protesting millennials and the pro-China population. However, there has been no death in police action so far.

Beijing seems to be in a dilemma—whether to allow more freedom and democracy in Hong Kong or let the army move in, as it did in 1989 at the Tiananmen Square, and brutally crush the movement. Allowing Western-style democracy in Hong Kong can trigger off similar demands in mainland China.

Hong Kong grew in importance in the 1950s when it gradually became a manufacturing hub and the international financial centre of the Asia-Pacific region, because of its geographic location and business-friendly atmosphere. It is extremely important to both China and the business houses around the world. Beijing is aware that Hong Kong attracts international attention because of its importance.

China has accused Britain of inciting violence in Hong Kong and exchanged vitriol with London. Beijing is unlikely to buckle under pressure but it also does not want any bloodshed. The coming weeks may see a hardening of Beijing's stand and Carrie Lam making more arrests of young leaders.

The movement in Hong Kong is a personal challenge to Xi Jinping. Maintaining law and order and peace in the territory and keeping the wheels of Hong Kong's financial hub churning is Xi Jinping's primary objective. Any bloodshed will drive off international businesses and make the territory an unsafe place.

Mahmood Hasan is a former ambassador and secretary of Bangladesh government.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments