Cowards strung together in a daisy chain

Sometime in the 1960s, a judge in Barisal had taken his own life. He hanged himself after he had learned that his wife was intercepted at the Benapole border for carrying gold jewellery in excess of the allowable limit. The husband apparently felt too ashamed of his wife's indiscretion to face the embarrassment. Those who found his lifeless body assessed that if he wanted, he could have easily saved himself at the last minute by planting his feet on a chair, which was within his reach. Shame, in those days, worked like the sprinkler system in a high-rise building. It activated itself whenever there was fire.

Now, that sprinkler system is all but broken. Shame is a word that has been erased from our minds. We no longer experience the painful feeling of humiliation or distress caused by the consciousness of wrong or foolish behaviour. Nothing seems to make us ashamed of ourselves anymore.

Once it was shameful to lie, steal and cheat, and an entire family could be ostracised if they brought shame upon a village or neighbourhood. It was also shameful to keep bad company. People frowned upon anybody who lived beyond his means. Anybody failing to keep a promise invited public scorn. Not too long ago, chronic debtors admitted themselves in hospitals to avoid harassment by cranky creditors.

It's believed that the root of the word shame is derived from an older word which means "to cover." For example, an individual covering himself is a natural expression of shame. This physical connotation eventually projected itself onto the mental, and formed the basis of human decency that signified our civilisation. Metaphorically, shame as an emotion is like a garment or cloak that covers the ethically naked self and gives it an acceptable social identity.

There have been times when shame was serious business. The samurais in Japan had their bushido or code of honour which involved dying by committing seppuku to avoid shame. Former South Korean president Roh Moo-Hyun committed suicide by leaping from a hill amid an investigation over a bribery scandal. Robert A Kaster wrote in the American Philological Association's 1996 Presidential Address titled "The Shame of the Romans" that in ancient Rome an academic suffered pudor or shame if he failed publicly to answer a question in his area of expertise. He also mentioned that a philosopher named Diodorus is said to have literally died of shame from just that cause.

Shame is thus the flipside of honour, and one can't exist without the other. Shameless people can't be honourable, and honourable people can't be shameless. This contradiction is deeply ensconced in our society where so many of us are so aggressively shameless, while at the same time also arduously vying for honour.

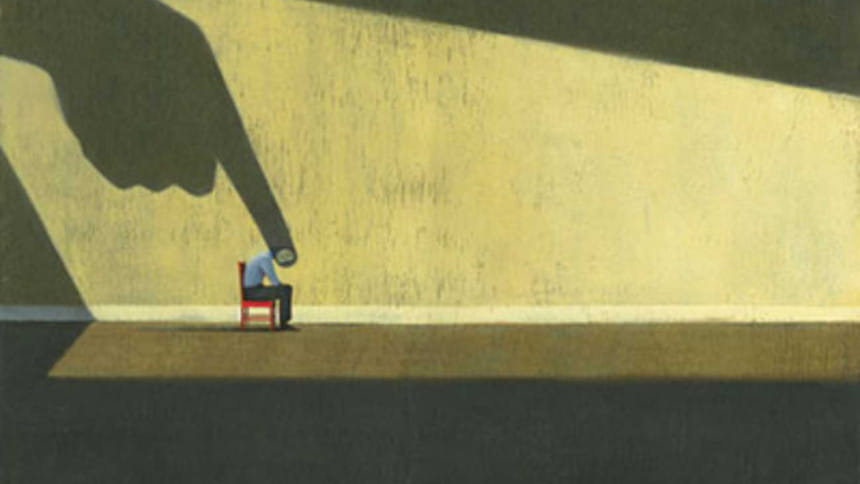

Questionable income, dubious education, fake credentials, false promises, flagrant falsehood, and audacity of pretence have abraded the cover. We're living in a see-through society where everybody sees what everybody does, but nobody dares to speak up against the guilt of others or admit his own. Instead of having to struggle with shame, we have given up shame altogether.

Children know their parents take bribes. Parents know their children watch pornography. Subordinates know their bosses are dishonest. Bosses know their subordinates are no better. Students know their teachers are unfair. Teachers know their students are insincere. Voters know they never casted their votes. Lawmakers know they never got elected to office.

It's said that shame pertains to a person, and guilt pertains to an action. In other words, shame is when someone thinks he or she is bad; guilt is when someone thinks he or she has done something bad. Immanuel Kant and his followers held that shame comes from others. Others, including Bernard Williams, argue that shame comes from oneself.

In either sense, shame as a realisation has been banished from our lives. If it still exists anywhere, it's in the dark recesses of our shifty hearts where conscience plays one-handed solitaire – to be won after all cards are discarded one by one. Anxiety of the conscience is no longer caused by the uneasiness about the rightness of an action. Instead, there's growing fascination for finding comfort in discarding rightness in every single action.

The judge in Barisal will never know that times have changed. Honour of men speaks of nothing but the hollowness ringing in them. Once, men died to save honour. Now, honour dies to save men. Anyone hiding from himself is hiding from others, producing a trail of cowards strung together in a daisy chain.

The writer is the Editor of weekly First News and an opinion writer for The Daily Star.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments