Economic challenges in 2019

The curtains are falling on the year 2018 and for our economy it was yet again a roller coaster ride of achievements and disappointments. Challenges remain but if our economy's long history of unfaltering resilience is any guide, sooner or later we are going to overcome them.

And resilience we will need in plenty with parliamentary elections approaching fast, and bringing with it the uncertainty that has, in the past, put a damper on economic activity. We have already seen stock prices tumble and private credit growth stagnate as political tensions slowly reach a boiling point. But thankfully, this time around the economy has not at least fallen prey to an endless stream of hartals and destructive violence that almost brought economic activity to a standstill in previous years. We can only hope that it stays that way in 2019.

Indeed, the economy has a lot to write home about in 2018. For starters, Bangladesh is well on its way to graduating out of the United Nation's LDC status and entering the league of developing countries in 2024. Remittance inflows, which suffered in the recent past, rebounded strongly in FY2017-18 growing by 17.3 percent, helping keep foreign exchange reserves well above USD 30 billion. Inflation remained comfortably below 6 percent while GDP growth was recorded at a whopping 7.9 percent, driven primarily by the manufacturing sector.

That said, those of us who follow economic reports of international agencies (World Bank, International Monetary Fund) remain a bit sceptical that growth was indeed so high, though we certainly believe it has been on an upward trajectory in recent times.

For all its imperfections, growth in GDP will and should remain the most followed economic indicator of 2019 by policymakers, industry leaders and researchers alike. After all, no other macro variable is so intricately linked with most other economic indicators. So instead of denouncing GDP growth as an erroneous measure of progress, we will be better off ensuring accurate reporting of these numbers by our statistical agencies. The challenge is then to ensure proper staffing of the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics and creating an independent institution that reports these numbers without any bias.

Macroeconomic stability—the hallmark of our economy—came under serious pressure this year owing to a combination of financial, fiscal and external sector imbalances. And combating these ongoing challenges next year will be no walk in the park. Authorities have to strike a careful balance of policies to alleviate an ongoing liquidity crisis in the banking sector while tackling the twin-deficit of a current account and fiscal deficit.

To be sure, many will again argue that reducing rates on national savings schemes is the panacea for these imbalances. Make no mistake, that will do little but hurt the elderly and retired who rely on these schemes for a decent living. Reducing delays in bank loan repayment, decreasing non-performing loans and curbing illicit outflow of funds will help alleviate both the current account deficit and the liquidity crisis in a more sustainable manner.

In 2019, the central bank will again find itself at a crossroads: selling foreign reserves to prevent exchange rate depreciation while aggravating the liquidity crisis or allowing a market-based depreciation of the currency. If the central bank stands aside, the rate of depreciation might be faster but it will help reduce the current account deficit by powering exports and remittance inflows, albeit with some lag.

For much of the last decade, igniting private investment and job creation, has remained one of the toughest challenges for policymakers. Not surprising since the remedy that it needs—quality fiscal stimulus for better infrastructure and efficient financial intermediation—remain elusive.

On the fiscal side, the less said about tax collection the better. Year in year out we see tax revenue receipts falling short of budgetary targets and this year was no different. Fundamental challenges such as a narrow tax base, tax evasion by the super-rich and lack of a simple and automated procedure for tax collection will remain big challenges in 2019.

When it comes to fiscal policy, collecting revenue is only one side of the challenge. Efficient utilisation of these resources is the other. A study by the International Monetary Fund found that countries with the most efficient public investment get "twice the growth bang for their public investment buck" than the least efficient. No points for guessing Bangladesh's rank in this efficiency spectrum. That the sharp rise in public investment to 8.0 per cent of GDP in recent years has hardly eased infrastructure constraints is evidence of low spending quality. Lowering cost overruns through higher accountability and transparency in cash management, creating a robust government procurement process and designing an incentive structure for public officials that ensures stringent monitoring and evaluation will be challenges yet again in 2019.

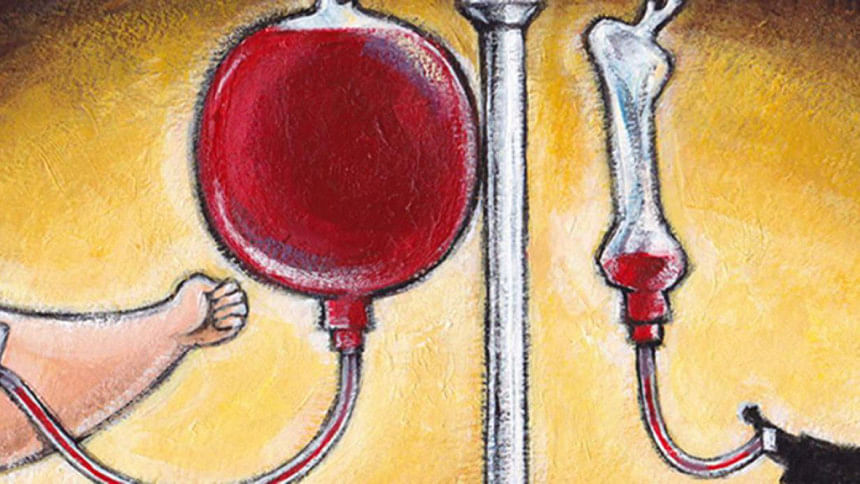

The fiscal challenge aside, private investors need efficient financiers. But an economy plagued by an ailing banking sector, a virtually non-existent corporate bond market and an underdeveloped stock market can never direct resources optimally from savers to borrowers. The challenge of cracking down on loan defaulters will remain a big one in 2019. It is unlikely that stakeholder confidence will be restored anytime soon in a sector where tax money is still used to capitalise graft-ridden state banks. Only time will tell for how much longer the poor will continue to pay the rich.

Meanwhile, we seem to have forgotten about developing a strong bond market. It doesn't even get its 15 minutes of fame in media outlets anymore. This is unfortunate, since deepening the bond market will provide corporations a new channel for saving and borrowing. A well-functioning bond market also strengthens monetary policy's interest-rate transmission mechanism and compel banks to be more efficient—and we all know that is long overdue. Will 2019 see steps towards creating a vibrant bond market?

Sadly though the stock market will remain disconnected from the economy, since the firms driving economic activity is not represented in the market. As I have written so many times in the past, big firms including multinational companies need to be listed to improve liquidity and public confidence. Twenty-eighteen saw next to no progress on this front, so we can only hope that 2019 doesn't disappoint as well.

Above all, those of us hoping to see equitable economic progress would like to see steps—however small they may be—towards strengthening institutions next year. History is replete with examples of economic success riding on the pillars of strong institutions. No matter how far we have come in our development journey, the gains from our success will never be shared equitably if institutions are weak. That means no red tape, an independent central bank, an empowered tax collection agency, a stronger capital market regulator and of course a government which can resist and punish influential and corrupt tycoons that threaten to kill the vitality of our economy.

Sharjil Haque is a Doctoral student in Economics at the University of North Carolina, USA and former Research Analyst, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC.

Comments